Pacific, Missouri

Pacific (formerly Franklin) is a city in the U.S. state of Missouri straddling the line between Franklin County and St. Louis County. The population was 7,002 at the 2010 census.[6]

Pacific, Missouri | |

|---|---|

| City of Pacific | |

Downtown Pacific in August 2013 | |

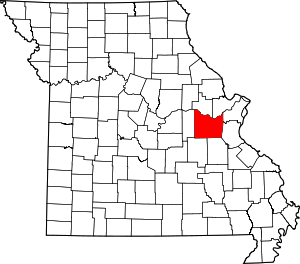

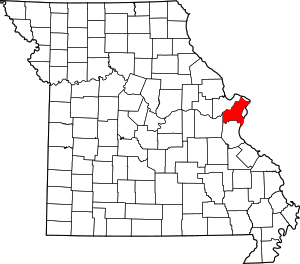

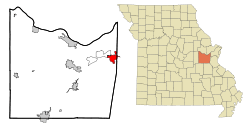

Location of Pacific, Missouri | |

| Coordinates: 38°28′53″N 90°45′0″W | |

| Country | United States of America |

| State | Missouri |

| Counties | Franklin, St. Louis |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Steve Myers |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.97 sq mi (15.46 km2) |

| • Land | 5.96 sq mi (15.43 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.03 km2) |

| Elevation | 466 ft (142 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 7,002 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 7,229 |

| • Density | 1,213.73/sq mi (468.61/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 63055, 63069 |

| Area code(s) | 636 |

| FIPS code | 29-55910[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0731630[5] |

| Website | www |

History

Early history (1820-1864)

Throughout the early 19th century, the area that would eventually become Pacific slowly developed, with the first log cabin being constructed in 1820 and a covered bridge across the nearby Meramec River being constructed in 1838.[7]

The Town of Franklin, Missouri was platted in 1852. The following year, the Pacific Railroad laid tracks in the town, and the railroad opened on July 19, 1853.[8] A post office was opened in 1854, and has continuously operated since.[9] The first city school was constructed in 1855.

In 1859, Franklin was incorporated as a fourth-class city and, in honor of the railroad, changed its name to Pacific.[10]

The Battle of Pacific (1864)

On October 1, 1864, as a part of former Missouri governor and Maj. Gen. Sterling Price's unsuccessful Missouri Expedition, a brigade of the Arkansas Cavalry of the Confederate States Army under the command of Gen. William Cabell was sent to Pacific from near Saint Clair. The brigade entered Pacific at sunrise and burned major city structures, including the rail depot and a number of bridges.

Union authorities in nearby Saint Louis quickly dispatched three divisions of the 16th Army Corps originally destined for Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman in Atlanta to Pacific to deal with Cabell's troops, who had, by most accounts, set up four pieces of artillery around the town.[11] The troops from St. Louis encountered Confederate troops just east of Pacific, near what is now Allenton, who shelled the train and the troops. The two brigades engaged in battle for a few hours, and when additional Union supports from Saint Louis arrived, Cabell's troops were forced out of the city to nearby Union, Missouri.

Given Pacific's proximity to the St. Louis County line, the city was seen as the last defense against an attempted Confederate invasion of Saint Louis. The casualties numbered about a dozen on each side, but Cabell's troops had done the bulk of their plundering earlier in the day.[12]

Post-war development (1864-1925)

The first issue of the Franklin County Democrat was published in Pacific in 1871, marking the first time a newspaper was published in the city. Production was moved to nearby Washington, Missouri on May 31, 1878, where the newspaper was published weekly until 1882.[13]

A new railroad depot was opened in 1882. It was used continuously until 1961, when regular service between Pacific and Saint Louis was discontinued due to declining ridership, and the Frisco Railroad abandoned the depot in 1976. It was demolished shortly thereafter.

In 1891, a fire at the center of town broke out, destroying all buildings on Saint Louis Street, the main commercial thoroughfare in Pacific, between First and Columbus Streets. In the following years, the Meramec River flooded the southern extent of Pacific a number of times, most notably in 1985 and 1915. The old covered bridge south of town was severely damaged by the former flood, and was demolished.[7]

The Missouri Botanical Garden purchased 1,300 acres (5.3 km2) of land immediately to the west of Pacific in 1925 when pollution from coal smoke in Saint Louis threatened the garden's extensive plant collection, notably its orchids. The orchids were moved to the land, then called the Gray Summit Extension, the following year, but were restored to the original location of the garden when pollution waned. The Missouri Botanical Garden kept the land, and over the next fifty years, amounting eventually to the 2,444 acre (9.89 km2) parcel currently known as Shaw Nature Reserve.

The Route 66 era (1925-1977)

U.S. Route 66 was commissioned by the federal government in 1926, but it originally did not go through Pacific; it was routed along what is now Missouri Route 100 east of Gray Summit going into Saint Louis until 1933. That year, U.S. Route 50 took over the 1926 alignment, and Route 66 was routed down what is now Osage Street through downtown Pacific. As Route 66 exploded in popularity through the 20th century, new attention was brought to Pacific, as cross-country motorists would stop in the city to eat and stay the night. The Red Cedar Inn, The Al-Pac Motel and Beacon Court, constructed in 1933, 1942 and 1946, respectively, are examples of bed and breakfasts that opened in Pacific along Route 66.[14]

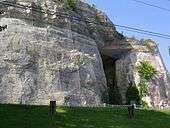

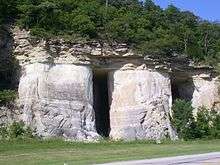

The Jensen's Point overlook, named for Lars P. Jensen, the first president of the Henry Shaw Gardenway Association, was constructed in 1939 by the Civilian Conservation Corps atop the sandstone bluffs towering above the Meramec River on the east side of town. It was restored by the city of Pacific in the late 2010s, and is open to the public, offering panoramic views of downtown Pacific and the Meramec River.[14]

In 1959, as part of Project Nike, the U.S. Air Force purchased some land approximately 5 miles (8 km) south of Pacific and constructed a Nike Hercules missile site on the land. Nike Base SL-60, as it was called, was one of four surface-to-air missile sites surrounding the Saint Louis metropolitan area in case of an imminent attack from the Soviet Union during the Cold War. It operated from 1960 until 1968.[15] The city of Pacific took control of the land in 1969 and the Meramec Valley R-III school district utilized the barracks to build an elementary school. The parcel is now mostly privately owned, with the airstrip becoming part of a residential subdivision later.

Interstate 44 was constructed throughout Missouri during the early 1960s, and when it opened in 1965, Pacific and Route 66 were bypassed immediately to the north by the highway. By 1972, the Interstate Highway System had completely bypassed Route 66, and in 1974, the AASHTO decided that Route 66 from Joplin, Missouri to Chicago, Illinois should be decommissioned. Former Route 66 was commissioned as Business Loop 44 through Pacific, and signs and shields referencing Route 66 in Pacific were removed in 1977.[14]

Modern growth (1977-present)

The Missouri Eastern Correctional Center, a medium-minimum security prison with the capacity to house 1,100 male inmates, was constructed immediately east of Pacific in 1979. The city annexed the prison in 2004 after a lengthy debate with neighboring Eureka, who claimed they had also intended to annex the prison.

In 1982, following the Meramec River flooding around Pacific, dioxin contaminants in oil used to spray down the dirt roads in nearby Times Beach were spread through the town, which caused disease and the eventual evacuation and demolition of the entire town. Some evacuants moved to Pacific, which caused a substantial population boom.

The Gustav Grauer Farm, located approximately 4 miles (6.4 km) north of Pacific in unincorporated Franklin County, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984.[16]

Geography

Pacific is located at 38°28′53″N 90°45′0″W (38.481503, -90.750015).[17] The city straddles the Franklin/St. Louis county line, which lies halfway on the blocks between Elm and Neosho streets. St. Louis is 30 miles (50 km) northeast of Pacific, and the communities comprising the Missouri Rhineland are 20 miles (30 km) northwest of the city.

Pacific is bordered on the southeast by the Pacific Palisades Conservation Area. Access to the Meramec River, through the Pacific Palisades Conservation Area, is located east of the city, adjacent to Eureka on the north side. The majority of the Pacific Palisades Conservation Area is south of the river and can be accessed 1 mile (1.6 km) south of the city in Jefferson County.

The Union Pacific (formerly Missouri Pacific) railroad, BNSF Railway (formerly St. Louis-San Francisco) Railroad, Historic U.S. Route 66, Brush Creek, and Fox Creek run through the town.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 5.93 square miles (15.36 km2), of which 5.92 square miles (15.33 km2) is land and 0.01 square miles (0.03 km2) is water.[18] A total of 1.7 sq mi (4.4 km2) of the city is located in St. Louis County. The city is located directly west from Eureka and 5 miles (8 km) east of Gray Summit.

Commercial areas

The Old Downtown Commerce Area is mostly located along First and St. Louis streets. The historic downtown buildings, built in the late 1800s, have been fully or partially restored, and new businesses have moved into the buildings.

The Red Cedar Inn, on the east end of town, was a meeting place for people around the country seeking out one of the oldest restaurants still standing on Route 66. The restaurant closed in 2007.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 437 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,208 | 176.4% | |

| 1880 | 1,275 | 5.5% | |

| 1890 | 1,184 | −7.1% | |

| 1900 | 1,213 | 2.4% | |

| 1910 | 1,418 | 16.9% | |

| 1920 | 1,275 | −10.1% | |

| 1930 | 1,456 | 14.2% | |

| 1940 | 1,687 | 15.9% | |

| 1950 | 1,985 | 17.7% | |

| 1960 | 2,795 | 40.8% | |

| 1970 | 3,247 | 16.2% | |

| 1980 | 4,410 | 35.8% | |

| 1990 | 4,350 | −1.4% | |

| 2000 | 5,482 | 26.0% | |

| 2010 | 7,002 | 27.7% | |

| Est. 2019 | 7,229 | [3] | 3.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[19] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 7,002 people, 2,368 households, and 1,524 families living in the city. The population density was 1,182.8 inhabitants per square mile (456.7/km2). There were 2,645 housing units at an average density of 446.8 per square mile (172.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 88.4% White, 8.4% African American, 0.6% Native American, 0.5% Asian, 0.6% from other races, and 1.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.9% of the population. The population total also includes the Missouri Eastern Correctional Facility which houses over 1,000 inmates.

There were 2,368 households, of which 32.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.4% were married couples living together, 14.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.1% had a male householder with no wife present, and 35.6% were non-families. 29.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 3.00.

The median age in the city was 35.9 years. 20% of residents were under the age of 18; 11.2% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 32.6% were from 25 to 44; 24.6% were from 45 to 64; and 11.5% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 55.6% male and 44.4% female.

2000 census

As of the census[4] of 2000, there were 5,482 people, 2,166 households, and 1,431 families living in the city. The population density was 1,011.0 people per square mile (390.5/km2). There are 2,343 housing units at an average Value at $97,987.22 /km2 (432.1/sq mi). The racial makeup of the city was 94.35% White, 2.92% African American, 0.38% Asian, 0.31% Native American, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.53% from other races, and 1.48% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.08% of the population.

There were 2,166 households, out of which 33.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.1% were married couples living together, 15.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.9% were non-families. 28.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.48 and the average family size was 3.05.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 26.6% under the age of 18, 9.4% from 18 to 24, 31.9% from 25 to 44, 19.7% from 45 to 64, and 12.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $39,554, and the median income for a family was $44,545. Males had a median income of $32,813 versus $22,529 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,865. About 8.8% of families and 14.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.7% of those under age 18 and 19.4% of those age 65 or over.

Government

Pacific is a fourth-class city with a city administrator government. The elected, policy-making body of the city consists of a Mayor and a six-member Board of Aldermen. Pacific is divided into three wards, each with two aldermanic representatives. Municipal elections are held every year on the first Tuesday of April.

Steve Roth, the current city administrator, is appointed by the Board of Aldermen and is the full-time administrative officer of the city, responsible for overseeing all daily operations and the municipal staff.

The current Mayor of Pacific is Steve Myers. He was elected in 2018.

| Candidate | Votes | Percentage | Party |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steve Myers | 732 | 60.90% | Non-partisan |

| Jerry Eversmeyer | 229 | 18.96% | Non-partisan |

| Stephen Flannery III | 243 | 20.12% | Non-partisan |

The Pacific Board of Aldermen has staggered elections. Each of the three wards has two aldermen representing them; one seat is up for election in odd-numbered years and the other in even-numbered years. Each alderman serves a two-year term, and there are no term limits.

| Ward | Representative | Last elected |

|---|---|---|

| Ward 1 | Harold "Butch" Frick | June 2, 2020 |

| Gregg P. Rahn | April 2, 2019 | |

| Ward 2 | Herbert Adams | June 2, 2020 |

| Carol Johnson | April 2, 2019 | |

| Ward 3 | Drew Stotler | June 2, 2020 |

| Andrew Nemeth | April 2, 2019 |

Education

Pacific and its surrounding communities are served by the Meramec Valley R-III school system and the St. Louis Community College district, and many residents attend nearby East Central College.

Elementary and secondary schools in the Meramec Valley School District:

- Coleman Elementary School

- Nike Elementary School

- Robertsville Elementary School

- Truman Elementary School

- Zitzman Elementary School

- Meramec Valley Early Childhood Center

- Meramec Valley Community School- formerly Pacific Middle School

- Pacific Intermediate- formerly Meramec Valley Middle School (5th & 6th grades)- formerly Pacific Junior High School

- Riverbend Middle School (7th & 8th grades)

- Pacific High School

Pacific has a public library, a branch of the Scenic Regional Library system.[20]

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Race, Hispanic or Latino, Age, and Housing Occupancy: 2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File (QT-PL), Pacific city, Missouri". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- "History of Pacific". City of Pacific, Missouri.

- "Franklin County Place Names, 1928–1945 (archived)". The State Historical Society of Missouri. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Post Offices". Jim Forte Postal History. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- Eaton, David Wolfe (1916). How Missouri Counties, Towns and Streams Were Named. The State Historical Society of Missouri. pp. 168.

- "The Battle of Pacific: Missouri's Civil War" (PDF). Missouri Civil War Heritage Foundation. 2010.

- Swain, Craig (2014-10-02). "The "high water mark" of his campaign: Price approaches St. Louis". To the Sound of the Guns. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "Franklin County Democrat (Pacific, Mo.) 1871-1882". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- Whittall, Austin. "Pacific, Missouri. Route 66: Attractions and Landmarks". www.theroute-66.com. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "Nike Missle Base Reunion May 30n Operated 1958 to 1968". The Missourian. Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-01-25. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Locations and Hours". Scenic Regional Library. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pacific, Missouri. |

- City of Pacific official website

- Pacific Area Chamber of Commerce

- Historic maps of Pacific in the Sanborn Maps of Missouri Collection at the University of Missouri