Caribou Inuit

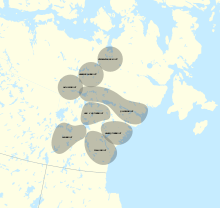

Caribou Inuit (Inuktitut: Kivallirmiut/ᑭᕙᓪᓕᕐᒥᐅᑦ), barren-ground caribou hunters, are bands of inland Inuit who lived west of Hudson Bay in Keewatin Region, Northwest Territories, now the Kivalliq Region of present-day Nunavut between 61° and 65° N and 90° and 102° W in Northern Canada. They were originally named "Caribou Eskimo" by the Danish Fifth Thule Expedition of 1921-4 led by Knud Rasmussen.[1][2] Caribou Inuit are the southernmost subgroup of the Central Inuit.[3][4]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Nunavut | |

| Languages | |

| Inuktitut | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Inuit religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Copper Inuit |

Bands

- Ahialmiut

Ahialmiut relied on caribou year-round. They spent summers on the Qamanirjuaq calving grounds at Qamanirjuaq Lake ("huge lake adjoining a river at both ends") and spent winters following the herd to the north.[5]

- Akilinirmiut

Akilinirmiut were located in the Thelon River area by the Akiliniq Hills (A-ki, meaning "the other side") to the north of Beverly Lake and also visible above Aberdeen Lake. Some lived northwest of Baker Lake (Qamani'tuuaq), along with Qairnirmiut and Hauniqturmiut. Many relocated to Aberdeen Lake because of starvation or education opportunities.[6][7][8][9][10]

- Hanningajurmiut

Hanningajurmiut, or Hanningaruqmiut, or Hanningajulinmiut {"the people of the place that lies across"} lived at Garry Lake, south of the Utkuhiksalingmiut. Many Hanningajurmiut starved in 1958 when the caribou bypassed their traditional hunting grounds, but the 31 who survived were relocated to Baker. Most never returned permanently to Garry Lake.[11][12][13][14]

- Harvaqtuurmiut

Harvaqtuurmiut were a northern group located in the region of Kazan River, Yathkyed Lake, Kunwak River, Beverly Lake, and Dubawnt River. By the early 1980s, most lived at Baker Lake.[2][15]

- Hauniqtuurmiut

Hauneqtormiut, or Hauniqtuurmiut, or Kangiqliniqmiut, ("dwellers where bones abound") were a smaller band who lived near the coast, south of Qairnirmiuts, around the Wilson River and Ferguson River. By the 1980s, they were absorbed into subgroups at Whale Cove and Rankin Inlet.[4][15][16]

- Ihalmiut

Ihalmiut ("people from beyond"), or Ahiarmiut ("the out-of-the-way dwellers") were located at the banks of the Kazan River, Ennadai Lake, Little Dubawnt Lake (Kamilikuak), and north of Thlewiaza (Kugjuaq; "Big River"). Relocations in the 1950s included to Henik Lake, Whale Cove, and by the 1980s, most were in Eskimo Point.[4][15][17][18][19][20][21]

- Paallirmiut

Paallirmiut ("people of the willow"), or Padlermiut ("people from the Padlei River region"), or Padleimiut were the most populous band. They were located south of the Hauniqtuurmiut and Harvaqtuurmiut bands. Paallirmiut were split into a coast-visiting (Arviat) subgroup who spent the hunting season on the lower Maguse River, and an interior subgroup who stayed year-round in the Yathkyed Lake to Dubawnt Lake area. After Hudson's Bay Company ships discontinued trading the Keewatin coast in 1790, Paallirmiut traveled to Fort Prince of Wales for trade. The Arvia'juaq and Qikiqtaarjuk National Historic Site is the band's historic summer camping site. By the 1980s, most lived in Eskimo Point (Arviat).[4][15][16][22][23]

- Qaernermiut

Qaernermiut ("dwellers of the flat land"), or Qairnirmiut ("bedrock people"), or Kinipetu (Franz Boas, 1901), or Kenepetu, a northern group, were located from the sea coast between Chesterfield Inlet to Rankin Inlet across to their main area around Baker Lake and some even to Beverly Lake. By the early 1980s, most lived at Baker Lake.[2][4] [15][16]

- Utkuhiksalingmiut

Utkuhiksalingmiut ("people who have cooking pots"), were located in the Chantrey Inlet area around the Back River, near Baker Lake. They made their pots (utkusik) from soapstone of the area, therefore their name. Their dialect is a variant of Natsilingmiutut, spoken by the Netsilik.[6][24][25]

Origin

Lacking an early written language, Caribou Inuit pre-history is unclear. There are three main theories:[26][27]

- Caribou Inuit are the descendants of an interior Eskimo culture that spread in Arctic North America and Greenland. (Birket-Smith, 1930; Rasmussen, 1930; Czonka, 1995)

- Caribou Inuit are the descendants of Thule people who had migrated from Alaska. (Mathiassen, 1927)

- Caribou Inuit were the 17th century descendants of a migratory subgroup of Copper Inuit from the arctic coast. (Taylor, 1972; Burch, 1978) While this is the most current hypothesis, it is still unproven. (Czonka, 1998)

History

Caribou Inuit ancestors originally went back and forth between the Barrenlands to hunt the Beverly and the Qamanirjuaq ("Kaminuriak") caribou herds during seasonal migrations; and the Hudson Bay (Tariurjuaq) for whaling and to fish during the winters. The Chipewyan Sayisi Dene were caribou hunters also, but they stayed inland year-round. Because of waning caribou populations during extended periods, including the 18th century, the Dene moved away from the area, and the Caribou Inuit began to live inland year-round harvesting enough caribou to get through winters without reliance on coastal life.[28]

Regular contact began around 1717 after the establishment of a permanent settlement in Churchill, Manitoba. The contact included access to guns, along with an introduction to trapping and whaling. Christian missionary, Father Alphonse Gasté, made diary notes about peaceful relations between settled Caribou Inuit and migratory Dene that he met along the Kazan River in the late 19th century. Explorer Joseph Tyrrell estimated the "Caribou Eskimo" numbered nearly 2,000 when he led the Geological Survey of Canada's Barren Lands expeditions of 1893 and 1894. Eugene Arima classifies the Hauniqtuurmiut, Ha'vaqtuurmiut, Paallirmiut, and Qairnirmiut as Caribou Inuit "southern, latter" bands: through the end of the 19th century, they were primarily coastal saltwater hunters, but with firearm ammunition from commercial whalers, they were able to live inland year-round hunting caribou without augmenting their diet on sea life. (Arima 1975)[1][3][28]

Regular trade dates to the early 20th century and missionaries arrived soon thereafter, developing a written language, challenged by a variety of pronunciations and naming rules. In the Arctic spring of 1922, explorer/anthropologist Kaj Birket-Smith and Rasmussen encountered and reported on the lives of Harvaqtuurmiut and Paallirmiut. Some hunting years were better than others as resident caribou and migratory herds grew or declined, but Caribou Inuit populations dwindled through the decades. Starvation was not uncommon. During a bleak period in the 1920s, some of the Caribou Inuit made their way to Hudson's Bay Company outposts and small, scattered villages on their own. In the early 1950s the Canadian media reported the starvation deaths of 60 Caribou Inuit.[29] The government was slow to act but in 1959 moved the surviving 60, of around the 120 that were alive in 1950, to settlements such as Baker Lake and Eskimo Point.[29] This set off an Arctic settlement push by the Canadian government where those First Nations living in the North were encouraged to abandon their traditional way of life and settle in villages and outposts of the Canadian North.[29] Author/explorer Farley Mowat visited the Ihalmiut in the 1940s and 1950s, writing extensively about the Ihalmiut.[6][18][30][31]

Ethnography

.jpg)

Caribou Inuit were nomadic and summers were time of relocation to reach different game and to trade. In addition to hunting, they fished in local lakes and rivers (kuuk). Caribou Inuit northern bands from as far away as Dubawnt River travelled on trading trips to Churchill via Thlewiaza River for extra supplies. The nomadic nature made the people and their dogs into strong walkers and sledders who carried loads of implements, bedding, and tents. Kayaks portaged people and baggage in rivers and lakes.[2][21]

Kayaks were also used for hunting at water crossings during annual migration. Wounded animals were tied together, brought ashore, and killed there to avoid the struggle of dragging dead animals. Every part of the caribou was important. The antlers were used for tools, such as the ulu ("knife") and goggles to prevent snow blindness. The hides were used for footwear and clothing, including the anorak and amauti, using caribou sinew to piece the articles together, and worn in many layers. Mittens were lined with fur, down, and moss. While spring-gathered caribou skins were thin, sleek, and handsome, summer-gathered caribou skins were stronger and warmer. Hides were used also for tents, tools, and containers.[2][3][15][32][33]

Caribou Inuit lived within a patrilocal social unit. The male elder, the ihumataq ("group leader"), was the centralized authority. There was no other form of authority within subgroups or within the Caribou Inuit in general. Like other Inuit, Caribou Inuit practiced an animist religion, including beliefs that everything had a soul or energy with a disposition or personality. The protector was Pinga, a female figure, the object of taboos, who brings the dead to Adlivun. The supreme force was Hila ("air"), a male figure and the source of misfortune. Christian missionaries established posts in the Barren Lands between 1910 and 1930, converting (siqqitiq) most Inuit from animists to Christians, though some, nonetheless, maintain remnants of their traditional shamanistic beliefs.[1][34]

Caribou Inuit are Inuktitut speakers. Inuktitut has six dialects, of which Caribou Inuit speak the Kivalliq dialect, and that is further divided into the subdialects, Ahiarmiut, Hauniqturmiut, Paallirmiut, and Qairnirmiut. The Utkuhiksalingmiut's dialect, Utkuhiksalingmiutut, is similar to but distinct from their neighbors' Nattilingmiutut. Like other central Canadian Arctic people, Caribou Inuit participated in nipaquhiit ("games done with sounds or with noises"). The Caribou Inuit genre lacked typical katajjaq ("throat sounds") but added narration missing amongst other Inuit groups.[15][35][36]

Modern-day adaptation

- Re-settlement

There are several books written on the hardships and the 1950s federal government re-settlement of Caribou Inuit. With re-settlement to coastal communities, the nomadic nuunamiut ("people of the land") ways ended and Caribou Inuit joined tareumiut ("people of the sea"), the maritime Inuit being a more stable group. Even with federal assistance, adapting to displacement in fewer and larger towns proved difficult, resulting in high unemployment, domestic violence, sexual abuse, substance addiction, suicide, and parental neglect.

- Language

With the acquisition of English, native language loss is the primary threat to their cultural survival, while neither language is being mastered.[37]

- Art

On a positive note, artisan skills evolved and Caribou Inuit, such as Jessie Oonark, are notable for their figurines of animal life. Another Inuit art medium, also considered a game, and also associated with their religious beliefs, involves string figures (ajaraaq/ajaqaat [plural]).[37][38][39]

- Population

About 3,000 Caribou Inuit exist today, located in Chesterfield Inlet, Rankin Inlet, Whale Cove, Arviat, and Baker Lake.[1]

Bibliography

Notes

- "Caribou Inuit". everyculture.com. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- Arima, E. (June 1994). "Caribou and Iglulik Inuit Kayaks" (PDF). Arctic. ucalgary.ca. 47 (2): 193–195. doi:10.14430/arctic1289. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- Cummins, B.D. (2004). Faces of the North: the ethnographic photography of John Honigmann. Toronto: Natural Heritage/Natural History. p. 149. ISBN 1-896219-79-9. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- Issenman, B. (1997). Sinews of survival: the living legacy of Inuit clothing (pdf). Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-7748-0596-X. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- "History & Culture - Qamanirjuwhat?" (PDF). 3 (2). Hudson Bay Post. October 2007: 10–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-16. Retrieved 2008-02-12. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Keith, Darren. "Baker Lake". inuitarteskimoart.com. Archived from the original on 2007-06-27. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- "Features". nunavutparks.com. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- Noah, William. "Involving Northern Communities in Project Development". cogema.ca. Archived from the original on 2012-07-30. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- "Hamlet of Baker Lake". bakerlake.org. Archived from the original on 2007-10-19. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- "Tuhaalruuqtut Ancestral Sounds". virtualmuseum.ca. Archived from the original on 2007-12-19. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- Tester, F.J.; Kulchyski, P. (1994-01-01). Tammarniit (Mistakes), Inuit Relocation in the Eastern Arctic, 1939-63. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0452-3. Archived from the original on 2007-11-29. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- "Hannah Kigusiuq". spiritwrestler.com. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- Dyck, C.J.; Briggs, J.L. (2004-05-16). "Historical developments in Utkuhiksalik phonology" (PDF). utoronto.ca. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- "Baker Lake, Nunavut". edu.nu.ca. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- Bouchard, Michel. "Inuit or Eskimo". University of the Arctic. Archived from the original on 2014-07-07. Retrieved 2007-12-27.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Inuit Map of the Canadian Arctic". jimmymacdonald.com. Archived from the original on 2007-11-01. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- Mowat, Farley (2001). Walking on the land. South Royalton, Vt.: Steerforth Press. ISBN 1-58642-024-0. OCLC 45667705.

- Madsen, Kirsten. "Project Caribou" (PDF). Whitehorse, Yukon Territory: Yukon Department of Environment. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- Mowat, Farley (2005). No Man's River. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 0-7867-1692-4. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- "Remembering Kikkik". nunatsiaq.com. 2002-06-21. Archived from the original on 2008-06-07. Retrieved 2007-12-22.

- Layman, Bill. "Nu-thel-tin-tu-eh and the Thlewiaza River, The Land of the Caribou Inuit and The Barren Ground Caribou Dene". churchillrivercanoe.com. Archived from the original on 2007-12-06. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- "Community Profile" (PDF). nativeaccess.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 22, 2006. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- "Clothing, footwear and territory of the Caribou Inuit". aaanativearts.com. Archived from the original on 2011-12-13. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- "Tuhaalruuqtut Ancestral Sounds". virtualmuseum.ca. Archived from the original on 2007-12-19. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- "Canadian Institute for research on linguistic minorities". Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- Keith, Darren (2004). "Caribou, river and ocean: Harvaqtuurmiut landscape organization and orientation". erudit.org. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- Birket-Smith, K. (1930). "The Question of the Origin of Eskimo Culture; a Rejoinder". American Anthropologist. 32 (4): 608–624. doi:10.1525/aa.1930.32.4.02a00030.

- "Kazan River". chrs.ca. Archived from the original on 2007-11-10. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- Bone 2013, p. 412

- Elder, Sarah (June 2002). "Padlei Diary, 19S0. An Account of the Padleimiut Eskimo in the Keewatin District West of Hudson Bay during the Early Months of 1950 as Witnessed". American Anthropologist. anthrosource.net. 104 (2): 657–659. doi:10.1525/aa.2002.104.2.657.

- People of the Deer. ASIN 0770420796.

- "Kivalliq (Inuit)". invitationproject.ca. Archived from the original on 2012-09-12. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- "Want to Stay Warm? Try a Caribou Suit". athropolis.com. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- Lee, R.B.; Daly, R.H. (1999). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Hunters and Gatherers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-521-57109-X. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- "Baby it's cold outside the igloo". blogspot.com. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- "Start of 8.0 Inuktitut dialects". languagegeek.com. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- Moran, E.F. (2002). Human Adaptability: An Introduction to Ecological Anthropology (pdf). Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. p. 116. ISBN 0-8133-1254-X. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- Probert, Martin. "Museums and other institutions with string figure artefacts". lineone.net. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- Wight, Darlene Coward. "The Winnipeg Art Gallery" (PDF). wag.mb.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

References

- Arima, E.Y. (1975). A contextual study of the Caribou Eskimo Kayak. Ottawa: National Museum of Man, Mercury Series 25. OCLC 1918154.

- Bone, Robert M.- Professor Department of Geography (2013). The Regional Geography of Canada. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199002429.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Total pages: 510

Further reading

- Buikstra, J. E. (1976). "The Caribou Eskimo: General and Specific Disease". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 45 (3): 351–67. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330450303. PMID 998764.

- Gordon, Bryan H. C. People of sunlight, people of starlight Barrenland archaeology in the Northwest Territories of Canada. Hull, Quebec: Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1996. ISBN 0-660-15963-5

- Oakes, Jill E. Copper and Caribou Inuit Skin Clothing Production. Mercury series. Hull, Quebec: Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1991. ISBN 0-660-12909-4

- Rasmussen, Knud. Iglulik and Caribou Eskimo Texts. New York: AMS Press, 1976. ISBN 0-404-58300-8

- Steenhoven, Geert van den, and Geert van den Steenhoven. Research Report on Caribou Eskimo Law. The Hague: G. van den Steenhoven, 1957.

- Thule Ekspedition, and Kaj Birket-Smith. The Caribou Eskimos Material and Social Life and Their Cultural Position. Washington, D.C.: Brookhaven Press, 1978.