Treaty of Brétigny

The Treaty of Brétigny was a treaty, drafted on 8 May 1360 and ratified on 24 October 1360, between King Edward III of England and King John II of France (the Good). In retrospect, it is seen as having marked the end of the first phase of the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453) as well as the height of English power on the Continent.

It was signed at Brétigny, a village near Chartres and later ratified as the Treaty of Calais on 24 October 1360.[1]

Background

The treaty was signed four years after John was taken as a prisoner of war at the Battle of Poitiers (19 September 1356). The ensuing conflicts in Paris between Étienne Marcel and the Dauphin (later King Charles V), and the outbreak of the Jacquerie peasant revolt weakened French bargaining power.

The exactions of the English, who wished to yield as few as possible of the advantages claimed by them in the abortive Treaty of London the year before, made negotiations difficult, and the discussion of terms begun early in April lasted more than a month.[2]

Terms

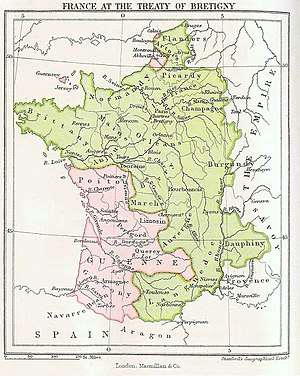

By virtue of this treaty, Edward III obtained, besides Guyenne and Gascony, Poitou, Saintonge and Aunis, Agenais, Périgord, Limousopn, Quercy, Bigorre, the countship of Gauré, Angoumois, Rouergue, Montreuil-sur-Mer, Ponthieu, Calais, Sangatte, Ham and the countship of Guînes.[2] The king of England was to hold these free and clear, without doing homage for them. Furthermore, the treaty established that title to 'all the islands that the King of England now holds' would no longer be under the suzerainty of the King of France.[1] The title Duke of Aquitaine was abandoned in favor of Lord of Aquitaine.

On his side, the King of England gave up the duchy of Touraine, the countships of Anjou and Maine, the suzerainty of Brittany and of Flanders.[2] He also renounced all claims to the French throne. The terms of Brétigny were meant to untangle the feudal responsibilities that had caused so much conflict, and, as far as the English were concerned, would concentrate English territories in an expanded version of Aquitaine. England also restored the rights of the Bishop of Coutances to Alderney, which had been stripped from them by the King of England in 1228.[3]

John II had to pay three million écus for his ransom, and would be released after he paid one million. The occasion was the first minting of the franc, equivalent to one livre tournois (twenty sous). As a guarantee for the payment of his ransom, John gave as hostages two of his sons, Louis I, Duke of Anjou and John, Duke of Berry, several princes and nobles, four inhabitants of Paris, and two citizens from each of the nineteen principal towns of France. This treaty was ratified and sworn to by the two kings and by their eldest sons, Edward, the Black Prince and the dauphin Charles on 24 October 1360 at Calais. At the same time, the special conditions relating to each important article of the treaty and the renunciatory clauses in which the kings abandoned their rights over the territory they had yielded to one another were signed.[2] Edward III retired finally to England.

Breakdown

While the hostages were held, John returned to France to try to raise funds to pay the ransom. In 1362, John's son, Louis of Anjou, a hostage in English-held Calais, escaped captivity. Thus, with his stand-in hostage gone, John felt honour-bound to return to captivity in England.[4][5] He died in captivity in 1364 and his son, Dauphin Charles, succeeded him as Charles V, king of France. In 1369, on the pretext that Edward III had failed to observe the terms of the treaty, the king of France declared war once again.

By the time of the 1377 death of Edward III, English forces had been pushed back into their territories in the southwest, around Bordeaux.

Legacy

The treaty did not lead to lasting peace, but procured nine years' respite from the Hundred Years' War. In the following years, French forces were involved in battles against the Anglo-Navarrese (Bertrand du Guesclin's victory at Cocherel on 16 May 1364) and the Bretons.

See also

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Brétigny. |

Notes

- p118 Hersch Lauterpacht, "Volume 20 of International Law Reports, Cambridge University Press, 1957, ISBN 0-521-46365-3

-

- Ben Cahoon. "Alderney". Worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 2014-02-16.

- Guignebert 1930, Volume 1. pp.304–307

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 501.

References

- Burne, Alfred H. The Crecy War: Military History of the Hundred Years War from 1337 to the Peace of Bretigny, 1360. Eyre & Spottiswoode: 1955. ISBN 0-8371-8301-4.

- Guignebert, Charles (1930). A Short History of the French People. Vol 1. F. G. Richmond Translator. New York: Macmillan and Company.