Orok language

Orok (also Ulta ульта, or Uilta, Ujlta уйльта[3]) is a language of the Manchu-Tungus family spoken in the Poronaysky and Nogliksky Administrative Divisions of Sakhalin Oblast, in the Russian Federation, by the small nomadic group known as the Orok or Ulta.

| Orok | |

|---|---|

| Uilta | |

| Native to | Russia, Japan |

| Region | Sakhalin Oblast (Russian Far East), Hokkaido |

| Ethnicity | 300 Orok (2010 census)[1] |

Native speakers | 26–47 (2010 census)[1] |

Tungusic

| |

| Cyrillic | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | oaa |

| Glottolog | orok1265[2] |

Classification

Orok is closely related to Nanai, and is classified within the southern branch of the Manchu-Tungus languages. Classifications which recognize an intermediate group between the northern and southern branch of Manchu-Tungus classify Orok (and Nanai) as Central Tungusic. Within Central Tungusic, Glottolog groups Orok with Ulch as "Ulchaic", and Ulchaic with Nanai as "Central-Western Tungusic" (also known as the "Nanai group"), while Oroch, Kilen and Udihe are grouped as "Central-Eastern Tungusic".[2]

Distribution

The language is critically endangered or moribund. According to the 2002 Russian census there were 346 Oroks living in the north-eastern part of Sakhalin, of whom 64 were competent in Orok. By the 2010 census, that number had dropped to 47. Oroks also live on the island of Hokkaido in Japan, but the number of speakers is uncertain, and certainly small.[4] Yamada (2010) reports 10 active speakers, 16 conditionally bilingual speakers, and 24 passive speakers who can understand with the help of Russian. The article states that "It is highly probable that the number has since decreased further."[5]

Orok is divided into two dialects, listed as Poronaisk (southern) and Val-Nogliki (northern).[2] The few Orok speakers in Hokkaido speak the southern dialect. "The distribution of Uilta is closely connected with their half-nomadic lifestyle, which involves reindeer herding as a subsistence economy."[5] The Southern Orok people stay in the coastal Okhotsk area in the Spring and Summer, and move to the North Sakhalin plains and East Sakhalin mountains during the Fall and Winter. The Northern Orok people live near the Terpenija Bay and the Poronai River during spring and summer, and migrate to the East Sakhalin mountains for autumn and winter.

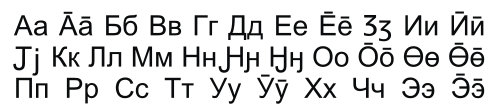

Alphabet

An alphabetic script, based on Cyrillic, was introduced in 2007. A primer has been published, and the language is taught in one school on the island of Sakhalin.[6]

The letter "en with left hook" has been included in Unicode since version 7.0.

In 2008, the first Uilta primer was published to set a writing system and to educated local speakers of Uilta.[7]

Phonology

Consonants

| Bilabial | Dental | Lateral | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | tʃ | k | (q) | |

| voiced | b | d | dʒ | ɡ | (ɢ) | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | s | x | (χ) | |||

| voiced | β | (z) | (ɣ) | (ʁ) | |||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||

| Liquid | r | l | ʎ | ||||

| Approximant | j | ||||||

Consonants in parentheses indicate allophones.

See also

References

- Orok at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Orok". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Uilta may come from the word ulaa which means 'domestic reindeer'. Tsumagari, Toshiro, 2009: "Grammatical Outline of Uilta (Revised)". Hokkaido University

- Novikova, 1997

- Yamada, Yoshiko, 2010: "A Preliminary Study of Language Contacts around Uilta in Sakhalin". Hokkaido University.

- Уилтадаирису (in Russian; retrieved 2011-08-17) ("Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link))

- Tsumagari, Toshiro, 2009: "Grammatical Outline of Uilta (Revised)". Hokkaido University

Further reading

- Majewicz, A. F. (1989). The Oroks: past and present (pp. 124–146). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Pilsudski, B. (1987). Materials for the study of the Orok [Uilta] language and folklore. In, Working papers / Institute of Linguistics Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu.

- Matsumura, K. (2002). Indigenous Minority Languages of Russia: A Bibliographical Guide.

- Kazama, Shinjiro. (2003). Basic vocabulary (A) of Tungusic languages. Endangered Languages of the Pacific Rim Publications Series, A2-037.

- Yamada, Yoshiko. (2010). A Preliminary Study of Language Contacts around Uilta in Sakhalin. Journal of the Center for Northern Humanities 3. 59-75.

- Tsumagari, T. (2009). Grammatical Outline of Uilta (Revised). Journal of the Graduate School of Letters, 41-21.

- Ikegami, J. (1994). Differences between the southern and northern dialects of Uilta. Bulletin of the Hokkaido Museum of Northern Peoples, 39-38.

- Knüppel, M. (2004). Uilta Oral Literature. A Collection of Texts Translated and Annotated. Revised and Enlarged Edition . (English). Zeitschrift für Ethnologie, 129(2), 317.

- Smolyak, A. B., & Anderson, G. S. (1996). Orok. Macmillan Reference USA.

- Missonova, L. (2010). The emergence of Uil'ta writing in the 21st century (problems of the ethno-social life of the languages of small peoples). Etnograficheskoe Obozrenie, 1100-115.

- Larisa, Ozolinya. (2013). A Grammar of Orok (Uilta). Novosibirsk Pablishing House Geo.

- Janhunen, J. (2014). On the ethnonyms Orok and Uryangkhai. Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia, (19), 71.

- Pevnov, A. M. (2009, March). On Some Features of Nivkh and Uilta (in Connection with Prospects of Russian-Japanese Collaboration). In サハリンの言語世界: 北大文学研究科公開シンポジウム報告書= Linguistic World of Sakhalin: Proceedings of the Symposium, September 6, 2008 (pp. 113–125). 北海道大学大学院文学研究科= Graduate School of Letters, Hokkaido University.

- Ikegami, J. (1997). Uirutago jiten [A dictionary of the Uilta language spoken on Sakhalin].

- K.A. Novikova, L.I. Sem. Oroksky yazyk // Yazyki mira: Tunguso-man'chzhurskie yazyki. Moscow, 1997. (Russian)

| Orok language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |