Omomyidae

Omomyidae is a family of early primates that radiated during the Eocene epoch between about 55 to 34 million years ago (mya). Fossil omomyids are found in North America, Europe, Asia, and possibly Africa, making it one of two groups of Eocene primates with a geographic distribution spanning holarctic continents, the other being the adapids (family Adapidae). Early representatives of the Omomyidae and Adapidae appear suddenly at the beginning of the Eocene (59 mya) in North America, Europe, and Asia, and are the earliest known crown primates.

| Omomyidae | |

|---|---|

| |

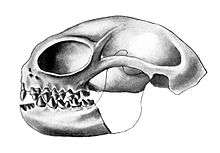

| The skull of Anaptomorphus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Tarsiiformes |

| Superfamily: | †Omomyoidea |

| Family: | †Omomyidae |

| Subfamilies | |

| |

Characteristics

Features that characterize many omomyids include large orbits (eye sockets), shortened rostra and dental arcades, loss of anterior premolars, cheek teeth adapted for insectivorous or frugivorous diets, and relatively small body mass (i.e., less than 500 g). However, by the late middle Eocene (about 40 mya), some North American omomyids (e.g., Macrotarsius) evolved body masses in excess of 1 kg and frugivorous or folivorous diets. Large orbits in genera such as Tetonius, Shoshonius, Necrolemur, and Microchoerus indicate that these taxa were probably nocturnal. At least one omomyid genus from the late Eocene of Texas (Rooneyia) had small orbits and was probably diurnal.

Like primates alive today, omomyids had grasping hands and feet with digits tipped by nails instead of claws, although they possessed toilet claws like modern lemurs.[2] Features of their skeletons strongly indicate that omomyids lived in trees. In at least one genus (Necrolemur), the lower leg bones, the tibia and fibula, were fused as in modern tarsiers. This feature may indicate that Necrolemur leaped frequently. Most other omomyid genera (e.g., Omomys) lack specializations for leaping, and their skeletons are more like those of living dwarf and mouse lemurs.

Omomyid systematics and evolutionary relationships are controversial. Various authors have suggested that omomyids are:

- stem haplorhines [i.e., basal members of the group including living tarsiers and anthropoids].

- stem tarsiiformes [i.e., basal offshoots of the tarsier lineage].

- stem primates more closely related to adapids than to living primate taxa.

Recent research suggests the Omomyformes are stem haplorhines, making them likely a paraphylectic grouping. [3]

Attempts to link omomyids to living groups have been complicated by their primitive (plesiomorphic) skeletal anatomy. For example, omomyids lack the numerous skeletal specializations of living haplorhines, including:

- significant reduction of the canal for the stapedial branch of the internal carotid artery.

- a "perbullar" (rather than "transpromontorial") route of the canal for the promontory branch of the internal carotid artery.

- contact between the alisphenoid and zygomatic bones.

- presence of an anterior accessory cavity confluent with the Tympanic cavity.

Omomyids further demonstrate a gap between the upper central incisors, which presumably indicates the presence of a rhinarium and philtrum to channel fluids into the vomeronasal organ. Omomyids as a group also lack most of the derived specializations of living tarsiers, such as extremely enlarged orbits (Shoshonius is a possible exception), a large suprameatal foramen for an anastomosis between the posterior auricular and middle meningeal circulation (again, Shoshonius is a possible exception, but the contents of the foramen in this extinct taxon are unknown), and extreme postcranial adaptations for leaping. In other respects (i.e., presence of an aphaneric, or intrabullar, ectotympanic bone connected to the lateral bullar wall by an unbroken annular bridge), omomyids are uniquely derived among primates.

Classification

- Family Omomyidae

- Altanius

- Altiatlasius

- Kohatius

- Subfamily Anaptomorphinae

- Tribe Trogolemurini

- Trogolemur

- Sphacorhysis

- Walshina

- Tribe Anaptomorphini

- Arapahovius

- Tatmanius

- Teilhardina

- Anemorhysis

- Chlororhysis

- Tetonius

- Pseudotetonius

- Absarokius

- Anaptomorphus

- Aycrossia

- Strigorhysis

- Mckennamorphus

- Gazinius

- Tribe Trogolemurini

- Subfamily Microchoerinae

- Indusomys

- Nannopithex

- Pseudoloris

- Necrolemur

- Microchoerus

- Vectipithex

- Melaneremia

- Paraloris

- Subfamily Omomyinae

- Brontomomys[4]

- Diablomomys

- Ekwiiyemakius[4]

- Gunnelltarsius[4]

- Huerfanius

- Mytonius

- Palaeacodon

- Tribe Rooneyini

- Tribe Steiniini

- Steinius

- Tribe Uintaniini

- Jemezius

- Uintanius

- Tribe Hemiacodontini

- Hemiacodon

- Tribe Omomyini

- Chumachius

- Omomys

- Tribe Macrotarsiini

- Yaquius

- Macrotarsius

- Tribe Washakiini

- Loveina

- Shoshonius

- Washakius

- Dyseolemur

- Tribe Utahiini

- Asiomomys

- Utahia

- Stockia

- Chipetaia

- Ourayia

- Wyomomys

- Ageitodendron

References

- Savage, RJG, & Long, MR (1986). Mammal Evolution: an illustrated guide. New York: Facts on File. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-8160-1194-0.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Early Primates Groomed with Claws".

- Rossie, James B.; Smith, Timothy D.; Beard, K. Christopher; Godinot, Marc; Rowe, Timothy B. (2018-01-01). "Nasolacrimal anatomy and haplorhine origins". Journal of Human Evolution. 114: 176–183. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.11.004. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 29447758.

- Amy L. Atwater; E. Christopher Kirk (2018). "New middle Eocene omomyines (Primates, Haplorhini) from San Diego County, California". Journal of Human Evolution. in press. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.04.010.