Okehampton Castle

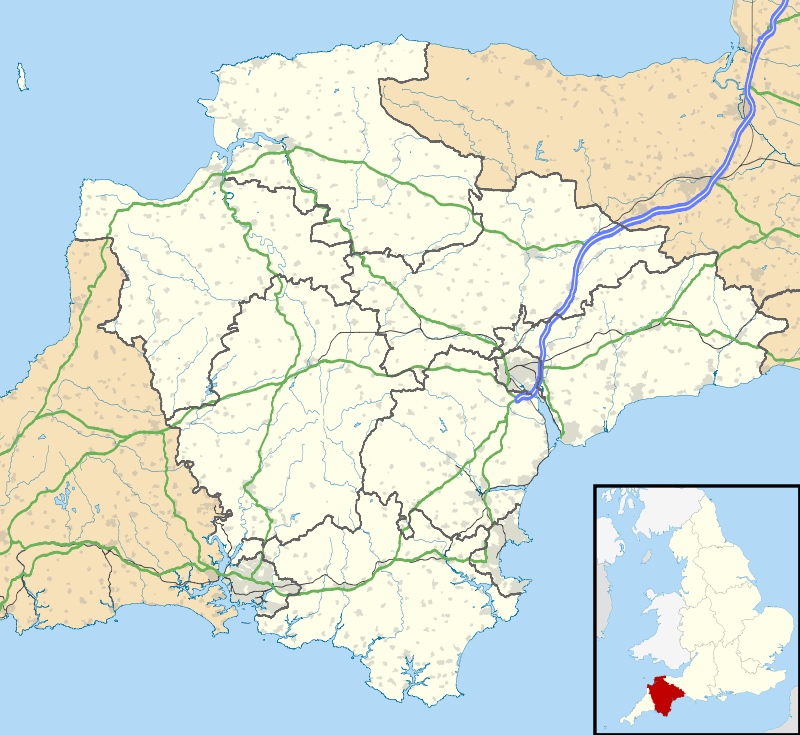

Okehampton Castle is a medieval motte and bailey castle in Devon, England. It was built between 1068 and 1086 by Baldwin FitzGilbert following a revolt in Devon against Norman rule, and formed the centre of the Honour of Okehampton, guarding a crossing point across the West Okement River. It continued in use as a fortification until the late 13th century, when its owners, the de Courtenays, became the Earls of Devon. With their new wealth, they redeveloped the castle as a luxurious hunting lodge, building a new deer park that stretched out south from the castle, and constructing fashionable lodgings that exploited the views across the landscape. The de Courtenays prospered and the castle was further expanded to accommodate their growing household.

| Okehampton Castle | |

|---|---|

| Okehampton, Devon, England | |

Keep of Okehampton Castle | |

Okehampton Castle | |

| Coordinates | 50.730515°N 4.008649°W |

| Grid reference | grid reference SX5833694246 |

| Type | Motte and bailey |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Stone |

The de Courtenays were heavily involved in the 15th century Wars of the Roses and Okehampton Castle was frequently confiscated. By the early 16th century the castle was still in good condition, but after Henry Courtenay was executed by Henry VIII the property was abandoned and left to decay, while the park was rented out by the Crown. Parts of the castle were reused as a bakery in the 17th century, but by the 19th century it was completely ruined and became popular with Picturesque painters, including J. M. W. Turner. Renovation work began properly in the 20th century, first under private ownership and then, more extensively, after the castle was acquired by the state. In the 21st century it is controlled by English Heritage and operated as a tourist attraction.

History

1066-1296

Okehampton Castle was built between 1068 and 1086 following the Norman conquest of England by Baldwin FitzGilbert.[1] William the Conqueror defeated the Anglo-Saxon forces at the battle of Hastings in 1066, but violence continued to flare up periodically for several years after the invasion. Baldwin FitzGilbert, a Norman lord, was responsible for putting down a rebellion in Devon in 1068.[2] He was probably given extensive lands in the county at this time, and by the time of Domesday Book in 1086 he was noted as the owner of the Honour of Okehampton and well as the Sheriff of Devon and Constable of Exeter Castle.[3] The Honour of Okehampton was a grouping of around 200 estates across Devon, guarded by several castles, including Baldwin's main castle - or caput - at Okehampton, and those owned by his tenants, including Neroche and Montacute.[4]

.jpg)

Baldwin's castle was positioned to protect an important route from Devon into Cornwall, including two fords that formed a crossing point over the West Okement River, and to control the existing town of Ocmundtune.[5] The castle was protected by a castle-guard system, in which lands were given out to Baldwin's tenants in exchange for their contributing to the castle's garrison.[6] Baldwin also established a new town near the castle about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) away, complete with a market and a mill to grind grain.[7] This town eventually dominated the older Anglo-Saxon settlement and became known as Okehampton.[7]

On Baldwin's death the castle was inherited by his daughter, Adeliza, but the family appear to have taken little interest in the property.[8] Okehampton Castle does not seem to have played a part in the civil war from 1139 and 1153 known as the Anarchy.[9]

In 1173 Okehampton Castle passed to Renaud de Courtenay in marriage; his son, Robert de Courtenay married the daughter of William de Redvers, the Earl of Devon.[10] The castle continued to have military utility and was requisitioned by Richard I between 1193 and 1194 to assist in the royal defence of Devon.[10] The de Courteneys carried out some building work at the castle, installing new structures in the castle bailey.[10] Robert was followed by his son John de Courtenay and by 1274, when John's son Hugh de Courtenay had inherited the property, the castle was reported to comprise only "an old motte which is worth nothing, and outside the motte a hall, chamber and kitchen poorly built", although this may underestimate the extent and condition of the castle.[10][nb 1]

1297-1455

The Redvers family line ran out in 1297, and as a result Hugh's son, another Hugh de Courtenay, inherited the Redvers family lands, later being confirmed as the Earl of Devon.[12] Hugh's main seat was at Tiverton Castle, but Hugh and his father redeveloped Okehampton Castle, expanding its facilities and accommodation to enable it be used as a hunting lodge and retreat.[13] Extensive building work turned the property into a luxurious residence.[14]

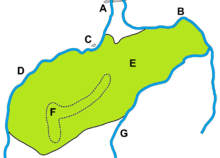

As part of this development, the family created a large, new deer park around the castle, replacing the older, unenclosed hunting grounds.[15] Deer parks were an important status symbol in this period, and many nobles who acquired power and wealth for the first time chose to undertake similar projects.[16] Creating the park, which spread out from the south of the castle to cover 690 hectares (1,700 acres), required clearing away the older settlements around the castle and abandoning various fields and pastures.[17] These settlements, comprising long houses built in warmer climate of the 12th and early 13th century, may already have become less sustainable due to the onset of the cooler climate that began to emerge at the end of the 13th.[18] Land near the castle, later called Kennel Field, was used to hold required the packs of dogs for hunting.[19]

Once the castle's deer park was established, intensively farmed fallow deer became common on the lands, although wild boar, foxes and hare were also hunted.[20] Like other rural castles, the occupants of Okehampton Castle consumed a relatively large amount of venison, a prestige meat during the period.[21] Some of this would have come from the surrounding deer park, but prime cuts of venison, such as the haunches, were also brought in specially from other locations.[21] Excavations have shown that in addition to fish from large ponds in the park, Okehampton Castle also imported fish from the coast, over 40 kilometres (25 mi) away, with hake, herring, plaice and whiting being most commonly eaten.[22]

The Courtenays continued to own Okehampton for many years, the property passing through Hugh's son, Hugh, to his grandson Edward and then his great-grandson, another Hugh de Courtnenay.[23] The size of noble households expanded during the period, and by the 1380s, when Edward controlled the castle, his "familiars", or extended household, could be up to 135 strong.[23] In the late 14th and early 15th centuries Okehampton Castle's facilities were extended further, probably to accommodate these increased numbers.[23]

1455-1900

In the 15th century, however, the Courtenays were embroiled in the civil conflict in England known as the Wars of the Roses between the rival alliances of the Lancastrians and the Yorkists.[24] Thomas de Courtenay fought for the Yorkists, but reconciled himself with the Lancastrians.[24] His son, Thomas, died following his capture by the Yorkists at the battle of Towton in 1461.[24] Edward IV confiscated Okehampton Castle, which was later returned to the family by the Lancastrian Henry VI.[24] John Courtenay died fighting for the Lancastrians at the battle of Tewkesbury in 1471 and the castle and earldom was again confiscated.[24] When Henry VII took the throne at the end of the conflict in 1485, however, the earldom and Okehampton were returned to Edward Courteney.[24]

Edward's son, William, enjoyed a turbulent political career, during which time the castle was again confiscated for a period, and his son, Henry, was executed by Henry VIII in 1539 and his properties confiscated, permanently breaking the link between the Courtenay family and the castle.[24] After his death, a survey praised the castle as having "all manner of houses of offices", but from this time onwards the castle appears to have been abandoned and left to decay, although there is evidence that the lead and some of the stonework was taken for use on other projects.[25] The castle's deer park was rented out by the Crown after Courtenay's execution.[26]

Ownership of the castle remained important, however, as from 1623 onwards ownership carried the right to appoint Okehampton's two Members of Parliament.[27] Despite the battle of Sourton Down being fought in 1643 near Okehampton during the English Civil War, the castle played no part in the conflict.[28] A bakehouse was established in the castle in the late-17th century, reusing parts of the western lodgings.[29] The deer park was disemparked during the 18th century, reverting to farmland.[30]

In the 18th century, the castle became a popular topic for painters interested in the then fashionable landscape styles of the Sublime and the Picturesque. Richard Wilson painted the castle in 1771, dramatically silhouetting the keep against the sky, producing what historian Jeremy Black describes as a "calm, entranching and melancholic" effect.[31] Thomas Walmesley's rendition went further, depicting Oakhampton Castle surrounded by an imaginary, Italianate lake in 1810.[32] Thomas Girtin painted the castle in 1797, as did his friend J. M. W. Turner in 1824.[33] Sir Vyell Vyvyan conducted some minor repairs to the castle during the 19th century.[34]

20th-21st centuries

In the early 20th century Okehampton Castle was bought by a local man, Sydney Simmons, who between 1911 and 1913 cleared away the vegetation that had grown over the castle and conducted some repairs to the stonework.[35] Simmons passed the castle to the Okehampton Castle Trust in 1917, who carried out limited repairs over the coming decades.[36] The Ministry of Public and Works took over the site in 1967 and extensive restoration work was subsequently carried out.[30] Extensive archaeological investigations were carried out in the 1970s at the site by Robert Higham.[30] In the 21st century, the castle is operated as a tourist attraction by English Heritage.[30] It is protected under law as an ancient monument and as a grade I listed building.[37]

Architecture

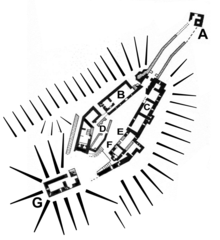

Okehampton Castle was built along a long, thin rocky outcrop, rising up from the surrounding countryside.[38] The stream that runs around the north side of the castle would have been more substantial in the medieval period and provided additional protection on that side, while the south side of the castle would have probably overlooked water-logged fields.[39] The castle was mostly built from local stone, with aplite from nearby Meldon and some beerstone from south-east Devon; the interior and exterior stonework would have originally been rendered with lime plaster.[40] The castle's final design involved a visitor entering from the barbican in the north-east, along a long passageway up the hill, into the bailey. On the south-west side of the bailey lay the motte, mounted by the keep.[41]

The castle's structure shows the results of its redesign at the start of the 14th century, using two very different forms of architecture. Seen from the north, where the main road carrying the general public made its way past, the castle had what Oliver Creighton terms a "martial facade" of traditional military defences, with narrow windows and towering defences.[42] Seen from the deer park on the south of the property, however, the castle's lodgings and accommodation were on full display, with low walls and large windows.[42] A similar architectural dichotomy can be seen at Ludlow and Warkworth Castles.[43] The park was effectively fused with the south side of the castle, with the chase running right up to the property.[44] From the two large windows of the eastern lodgings, it would have been possible to gaze out across the parklands and appreciate the extensive views without seeing any trace of rural settlements or the nearby town.[45] The result, as historian Stephen Mileson describes, would have been "stunning".[46]

The barbican was built at the beginning of the 14th century and contained a guard-room on the first floor.[47] The barbican contains numerous putlog holes from its construction, although these would have been masked by exterior plasterwork in the medieval period.[48] A passageway led up from the barbican to the gatehouse, probably originally guarded by a drawbridge and containing the accommodation for the castle's constable.[49]

The castle bailey contained a number of buildings by the 14th century. On the north side were the Great Hall, the buttery and the castle kitchens, the former lit by a large decorative window and partitionedfrom the kitchen and buttery by a wooden screen.[50] Above the buttery was a luxurious solar, or apartment.[51] On the south side of the bailey were the western lodgings, well-equipped accommodation for guests, built by in-filling part of the ditch between the motte and the bailey, and later converted into a bakery.[52] A chapel and accommodation for the castle's chaplain lay alongside, and the chapel has remaining plaster work, which shows that the walls were painted with red lines to resemble ashlar cut stone.[53] On the far side of the chapel were the eastern lodgings, whose detailing mirrored those at Tiverton Castle, another de Courtenay property built in the same period.[54]

The motte, on the far side of the bailey, is predominantly made up of a natural rock outcrop, strengthened further with earth from the construction of the rest of the castle ditches.[55] It stands up to 32 metres (105 ft) high and measures 29.5 metres (97 ft) by 15.5 metres (51 ft) at the top.[56] The motte is separated from the main castle by ditches in a similar way to the motte at Windsor Castle.[57] On top of the motte is the castle keep, originally built in the 11th century, with massive stone walls at least one storey high and possibly as high as three storeys, and then redeveloped as a two-storey structure with a rectangular addition on the western side in the early 14th century.[58] The 11th century parts of the keep make use of granite stone, probably taken from the river bed of the West Okement.[59] The 14th century keep had two sets of lodgings on the upper floor, similar in style to those in the bailey, and a turret containing a staircase, some of which still survives.[60]

The keep is unusual both for the period and for Devon as a whole, being a very strong defensive structure, albeit without any independent source of water or facilities to support a garrison in the event of a siege.[61] Other rectangular 11th century keeps in Devon existed, including at Exter and Lydford, and were typically associated with the king or major nobles.[62] Few were built on top of fresh mottes, as at Okehampton, and this may have been made possible in this case because the motte was largely natural and therefore able to support the heavy weight.[63]

References

Notes

- Medieval structural reports of this sort are treated with caution by historians, as they often focused on the problems of a property, rather than their strengths.[11]

References

- Higham 1977, p. 11

- Pounds 1994, p. 64

- Pounds 1994, p. 64; Endacott 1999, p. 24

- Pounds 1994, pp. 64–65; Endacott 1999, p. 24; Higham 1977, p. 13

- Endacott 1999, pp. 24–25; Creighton 2005, p. 158; Higham 1977, p. 4

- Higham 1977, p. 13

- Endacott 1999, pp. 25–26; Creighton 2005, p. 158

- Endacott 1999, p. 26

- Higham 1977, p. 13

- Endacott 1999, p. 27

- Higham 1977, p. 14

- Endacott 1999, p. 27; Mileson 2007, p. 23

- Creighton 2005, p. 67; Endacott 1999, p. 28

- Endacott 1999, p. 30

- Mileson 2007, p. 23; Creighton 2011, p. 88

- Mileson 2007, p. 23

- Creighton 2005, p. 191; Endacott 1999, p. 12

- Endacott 1999, pp. 28–29

- Endacott 1999, p. 12

- Endacott 1999, p. 12; Creighton 2005, p. 19

- Creighton 2005, p. 19

- Creighton 2005, pp. 15–16; Endacott 1999, p. 8

- Endacott 1999, p. 31

- Endacott 1999, p. 32

- Endacott 1999, p. 33; Higham 1977, p. 14

- Higham 1977, p. 4

- Endacott 1999, p. 33

- Endacott 1999, p. 34

- Endacott 1999, pp. 34–35

- Endacott 1999, p. 35

- Black 2005, p. 71

- Howard 1991, pp. 72–73

- Lane 1998, pp. 56–57; "Okehampton, on the Okement c.1824". Tate. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Higham 1977, p. 3

- Higham 1977, pp. 3–4, 25

- Endacott 1999, p. 35; Higham 1977, p. 4

- "Okehampton Castle". Gatehouse. 10 December 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Endacott 1999, pp. 24–25

- Higham 1977, pp. 7–8

- Endacott 1999, pp. 4, 5

- Endacott 1999, p. 37

- Creighton 2005, p. 67; Liddiard 2005, p. 127

- Liddiard 2005, p. 127

- Pluskowski 2007, p. 77

- Liddiard 2005, pp. 126–127; Creighton 2011, p. 88

- Mileson 2007, p. 24

- Endacott 1999, p. 3

- Endacott 1999, pp. 3–4

- Endacott 1999, p. 5

- Endacott 1999, pp. 5–6

- Endacott 1999, p. 7

- Endacott 1999, p. 15

- Higham & Allan 1980, p. 51

- Higham 1977, p. 11; Endacott 1999, pp. 19–21

- Creighton 2005, p. 37; Higham 1977, p. 7

- Higham 1977, p. 7

- Brown 1989, p. 22

- Higham 1977, pp. 8–10, 25, 29; Endacott 1999, p. 11

- Higham 1977, p. 25

- Higham 1977, p. 33; Endacott 1999, p. 11

- Higham 1977, p. 10

- Higham 1977, pp. 30, 32

- Higham 1977, pp. 30–31

Bibliography

- Black, Jeremy (2005). Culture in Eighteenth-Century England: a Subject for Taste. London, UK: Hambledon. ISBN 9781852855345.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, Reginald Allen (1989). Castles from the Air. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521329323.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Creighton, O. H. (2005). Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London, UK: Equinox. ISBN 9781904768678.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Creighton, O. H. (2011). "Seeing and Believing: Looking out on Medieval Castle Landscapes". Concilium Medii Aevi. 14: 79–91.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Endacott, Alan (1999). Okehampton Castle. London, UK: English Heritage. ISBN 9781850748250.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Higham, Robert A. (1977). "Excavations at Okehampton Castle, Devon. Part 1: the Motte and Keep". Devon Archaeological Society Proceedings. 35: 3–42.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Higham, Robert A.; Allan, J. P. (1980). "Excavations at Okehampton Castle, Devon. Part II: the Bailey. A Preliminary Report". Devon Archaeological Society Proceedings. 38: 49–51.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howard, Peter (1991). Landscapes: the Artists' Vision. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415007757.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lane, John (1998). In Praise of Devon: a Guide to Its People, Places and Character. Totnes, UK: Green Books. ISBN 9781870098755.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Liddiard, Robert (2005). Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press. ISBN 9780954557522.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mileson, Stephen A. (2007). "The Sociology of Park Creation in Medieval England". In Liddiard, Robert (ed.). The Medieval Park: New Perspectives. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press. pp. 11–26. ISBN 978-1-9051-1916-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pluskowski, Alexander (2007). "The Social Construction of Medieval Park Ecosystems: an Interdisciplinary Perspective". In Liddiard, Robert (ed.). The Medieval Park: New Perspectives. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press. pp. 63–78. ISBN 978-1-9051-1916-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pounds, Nigel J. G. (1994). The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45099-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Okehampton Castle. |