Nilgiri Mountains

The Nilgiri Mountains form part of the Western Ghats in western Tamil Nadu, India. At least 24 of the Nilgiri Mountains' peaks are above 2,000 metres (6,600 ft), the highest peak being Doddabetta, at 2,637 metres (8,652 ft).

| Nilgiri Mountains | |

|---|---|

View of Nilgiri Mountains | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Doddabetta, Tamil Nadu, India |

| Elevation | 2,637 m (8,652 ft) |

| Listing | Ultra List of Indian states and territories by highest point |

| Naming | |

| English translation | Blue Mountains, from Tamil |

| Geography | |

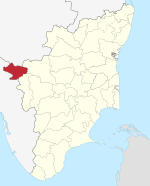

| Location | Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka |

| Parent range | Western Ghats |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Archean Eon, 3000 to 500 mya |

| Mountain type | Fault[1] |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | NH 67 (Satellite view) or Nilgiri Mountain Railway |

Etymology

The word Nilgiri, coming from Sanskrit neelam (blue) + giri (mountain), has been in use since at least 1117 CE.[2][3] It is thought that the bluish flowers of kurinji shrubs gave rise to the name.[4]

Location

The Nilgiri Hills are separated from the Karnataka Plateau to the north by the Moyar River.[5]

Three national parks border portions of the Nilgiri mountains. Mudumalai National Park lies in the northern part of the range where Kerala, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu meet, covering an area of 321 km². Mukurthi National Park lies in the southwest part of the range, in Kerala, covering an area of 78.5 km², which includes intact shola-grassland mosaic, habitat for the Nilgiri tahr. Silent Valley National Park lies just to the south and contiguous with those two parks, covering an area of 89.52 km².

Conservation

The Nilgiri Hills are part of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve (itself part of the UNESCO World Network of Biosphere Reserves.[6]), and form a part of the protected bio-reserves in India.

History

The high steppes of the Nilgiri Hills have been inhabited since prehistoric times, demonstrated by a large number of artifacts unearthed by excavators. A particularly important collection from the region can be seen in the British Museum, including those assembled by colonial officers James Wilkinson Breeks, Major M. J. Walhouse and Sir Walter Elliot.[7]

The first recorded use of the word Nila applied to this region can be traced back to 1117 AD. In the report of a general of Vishnuvardhana, King of Hoysalas, who in reference to his enemies, claimed to have "frightened the Todas, driven the Kongas underground, slaughtered the Poluvas, put to death the Maleyalas, terrified Chieftain Kala Nirpala and then proceeded to offer the peak of Nila Mountain (presumably Doddabetta or Rangaswami peak of Peranganad in East Nilgiris) to Lakshmi, Goddess of Wealth."[8]

A hero stone (Veeragallu) with a Kannada inscription at Vazhaithottam (Bale thota) in the Nilgiri District, dated to 10th century CE, has been discovered.[9] A Kannada inscription of Hoysala king Ballala III (or his subordinate Madhava Dannayaka's son) from the 14th century CE has been discovered at the Siva (or Vishnu) temple at Nilagiri Sadarana Kote (present-day Dannayakana Kote), near the junction of Moyar and Bhavani rivers, but the temple has since been submerged by the Bhavani Sagar dam.[9][10]

In 1814, as part of the Great Trigonometrical Survey, a sub-assistant named Keys and an apprentice named McMahon ascended the hills by the Danaynkeucottah (Dannayakana Kote) Pass, penetrated into the remotest parts, made plans, and sent in reports of their discoveries. As a result of these accounts, Messrs. Whish and Kindersley, two young Madras civilians, ventured up in pursuit of some criminals taking refuge in the mountains, and proceeded to observe the interior. They soon saw and felt enough favorable climate and terrain to excite their own curiosity, and that of others.[11]

After the early 1820s, the hills were developed rapidly under the British Raj, because most of the land was already privately owned by British citizens. It was a popular summer and weekend getaway for the British during the colonial days. In 1827, Ooty became the official sanatorium and the summer capital of the Madras Presidency. Many winding hill roads were built. In 1899, the Nilgiri Mountain Railway was completed by influential and enterprising British citizens, with venture capital from the Madras government.[12][13]

In the 19th century, when the British Straits Settlement shipped Chinese convicts to be jailed in India, the Chinese men settled in the Nilgiri mountains near Naduvattam after their release and married Tamil Paraiyan women, having mixed Chinese-Tamil children with them. They were documented by Edgar Thurston.[14]

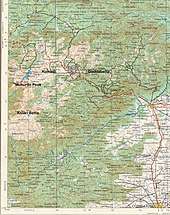

Peaks in the Nilgiris

The highest point in the Nilgiris and the southern extent of the range is Doddabetta Peak (2,637 metres (8,652 ft)),[15] 4 km east southeast of Udhagamandalam, 11°24′10″N 76°44′14″E.

Closely linked peaks in the west of Doddabetta range and nearby Udhagamandalam include:

- Kolaribetta: height: 2,630 metres (8,629 ft),

- Makurni (2594)m)

- Hecuba: 2,375 metres (7,792 ft),

- Kattadadu: 2,418 metres (7,933 ft) and

- Kulkudi: 2,439 metres (8,002 ft).

Snowdon (height: (2,530 metres (8,301 ft)) 11°26′N 76°46′E is the northern extent of the range. Club Hill (2,448 metres (8,031 ft)) and Elk Hill (2,466 metres (8,091 ft)) 11°23′55″N 76°42′39″E are significant elevations in this range. Snowdon, Club Hill and Elk Hill with Doddabetta, form the impressive Udhagamandalam Valley.

Devashola (height: 2,261 metres (7,418 ft)), notable for its blue gum trees, is in the south of Doddabetta range.

Kulakombai (1,707 metres (5,600 ft)) is east of the Devashola. The Bhavani Valley and the Lambton's peak range of Coimbatore district stretch from here.

Muttunadu Betta (height: 2,323 metres (7,621 ft)) 11°27′N 76°43′E is about 5 km, north northwest of Udhagamandalam. Tamrabetta (Coppery Hill) (height: 2,120 metres (6,955 ft)) 11°22′N 76°48′E is about 8 km southeast of Udhagamandalam. Vellangiri (Silvery Hill) (2,120 metres (6,955 ft)) is 16 km west-northwest of Udhagamandalam.[16]

Waterfalls

The highest waterfall, Kolakambai Fall, north of Kolakambai hill, has an unbroken fall of 400 ft (120 m). Nearby is the 150 ft (46 m) Halashana falls. The second highest is Catherine Falls, near Kotagiri, with a 250 ft (76 m) fall, named after the wife of M.D. Cockburn, believed to have introduced coffee plantations to the Nilgiri Hills. The Upper and Lower Pykara falls have falls of 180 ft (55 m), and 200 ft (61 m), respectively. The 170 ft (52 m) Kalhatti Falls is off the Segur Peak. The Karteri Fall, near Aruvankadu had the first power station which supplied the original Cordite Factory with electricity. Law's Fall, near Coonoor, is interesting due to its association with the engineer Major G. C. Law who supervised building of the Coonoor Ghat road.[17]

Flora and fauna

Over 2,700 species of flowering plants, 160 species of fern and fern allies, countless types of flowerless plants, mosses, fungi, algae, and land lichens are found in the sholas of the Nilgiris. No other hill station has so many exotic species.[18]

The Nilgiri tahr can be found in the hills.[19]

Much of the Nilgiris' natural montane grasslands and shrublands interspersed with sholas has been much disturbed or destroyed by extensive tea plantations, easy motor-vehicle access, extensive commercial planting and harvesting of non-native eucalyptus and wattle (Acacia dealbata, Acacia mearnsii) plantations, and cattle grazing.[20] The area also features one large and several smaller hydro-electric impoundments.[21] Scotch broom has become an ecologically damaging invasive species.[22]

Threatened plants of the Nilgiris include:

- Vulnerable species: Miliusa nilagirica, Nothapodytes foetida, Commelina wightii

- Rare species: Ceropegia decaisneana Ceropegia pusilla, Senecio kundaicus

- Endangered species: Youngia nilgiriensis, Impatiens neo-barnesii, Impatiens nilagirica, Euonymus angulatus and Euonymus serratifolius.[23]

Wild horse in pine forest

Wild horse in pine forest Vestalis submontana, endemic to Nilgiri

Vestalis submontana, endemic to Nilgiri_at_Periyar_National_Park_%26_Wildlife_Sanctuary.jpg) Herd of Gaur, Indian bisons.

Herd of Gaur, Indian bisons.

References

- "Application of GPS and GIS for the detailed Development planning". Map India 2000. 10 April 2000. Archived from the original on 3 June 2008. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- The Missionary Herald of the Baptist Missionary Society. Baptist Mission House. 1886. p. 398.

- Lengerke, Hans J. von (1977). The Nilgiris: Weather and Climate of a Mountain Area in South India. Steiner. p. 5. ISBN 9783515026406.

- "Decline of a Montane Ecosystem". Kartik Shanker Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science. February 1997.

- "Nilgiri Hills". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- UNESCO, World Heritage sites, Tentative lists, Western Ghats (subcluster nomination), retrieved 4/20/2007 World Heritage sites, Nilgiri Sub-Cluster

- "Collection search: You searched for Nilgiri". British Museum. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Pai, Mohan (15 January 2009). ...and they created little England. The Western Ghats - Hill Stations. the-western-ghats-by-mohan-pai-hill-stations, Egmore, Chennai. pp. Ootacamund.

- "Kannada script (10600)". Department of Archaeology - Tamil Nadu. Tamil Nadu Government. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- Francis, Walter (1908). Madras District Gazetteers: The Nilgiris. 1. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. pp. 90–94, 102–105. ISBN 978-81-2060-546-6.

- Burton, Richard Francis (1851). "Nilgiri Hills (India), Description and travel; Nilgiri Hills (India), Social life and customs". Goa, and the Blue Mountains, or, Six months of sick leave. London: R. Bentley.

- "Ooty Queen of hill stations". www.ooty.com. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- "Nilgiri Mountain Railway". railtourismindia.com. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- Sarat Chandra Roy (Rai Bahadur), ed. (1959). Man in India, Volume 39. A. K. Bose. p. 309. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

d: TAMIL-CHINESE CROSSES IN THE NILGIRIS, MADRAS. S. S. Sarkar* (Received on 21 September 1959) During May 1959, while working on the blood groups of the Kotas of the Nilgiri Hills in the village of Kokal in Gudalur, inquiries were made regarding the present position of the Tamil-Chinese cross described by Thurston (1909). It may be recalled here that Thurston reported the above cross resulting from the union of some Chinese convicts, deported from the Straits Settlement, and local Tamil Paraiyan

- Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. 271. ISBN 0-89577-087-3.

- District Administration, Nilgiris (8/20/2007) National Informatics Centre, Nilgiris, retrieved 8/31/2007 Hills and Peaks

- EAGAN, J. S. C (1916). The Nilgiri Guide And Directory. VEPERY: S.P.C.K. PRESS.

- The District Collector, Collector's Office, Udhagamandalam, The Nilgiris District, Tamil Nadu, General Information, RARE TREES, FRUITS, FLOWERS & ANIMALS retrieved 9/2/2007.

- "Nilgiri Tahr". WWF. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- Davidar, E. R. C. 1978. Distribution and status of the Nilgiri tahr (Hemitragus hylocrius) 1975-1978. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society; 75: 815-844.

- Rice, C G Dr (1984) US Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, USA, "The behaviour and ecology of Nilgiri Tahr", Tahr Foundation, retrieved 4/17/2007. Archived 28 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 103 (2-3), May-Dec 2006 356-365 HABITAT MODIFICATIONS BY SCOTCH BROOM CYTISUS SCOPARIUS INVASION OF GRASSLANDS OF THE UPPER NILGIRIS IN INDIA, ASHFAQ AHMED ZARRI1, 2, ASAD R. RAHMANI1,4 AND MARK J. BEHAN3 Archived 19 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Nayar & Sastry (1987-88) Red Data Book, Plants of India Threatened Plants of Tamil Nadu

External links

.jpg)