Nigali Sagar

Nigali Sagar, also called Nigliva,[1] is an archaeological site in Nepal containing the remains of a pillar of Ashoka. The pillar is called the Nigali Sagar pillar, or also the Nighihawa pillar, or Nigliva pillar, or Araurakot Asoka Pillar. The site is located about 20 kilometers northwest of Lumbini and 7 kilometers northeast of Taulihawa, Nepal.[2] Another famous inscription discovered nearby in a similar context is the Lumbini pillar inscription.

| Nigali Sagar pillar of Ashoka | |

|---|---|

The Nigali Sagar pillar, one of the pillars of Ashoka. | |

| Material | Polished sandstone |

| Size | Height: Width: |

| Period/culture | 3rd century BCE |

| Discovered | 27°35′41.7″N 83°05′44.9″E |

| Place | Nigalihawa, Nepal. |

| Present location | Nigalihawa, Nepal. |

Nigali Sagar  Nigali Sagar | |

Discovery

The pillar was initially discovered by a Nepalese officer on a hunting expedition.[3][4] The pillar and its inscriptions (there are several inscriptions on it, from Brahmi to Medieval) were researched in March 1895 by Alois Anton Führer.[1] Führer published his discovery in the Progress Report of the Archaeological Survey Circle, North-West Province, for the year ending on June 30, 1895.[1] The fact that the inscription was discovered by Alois Anton Führer, who is also known to have forged Brahmi inscriptions on ancient stone artefacts, casts a doubt on the authenticity of this inscription.[5]

The pillar was not erected in-situ, as no foundation has been discovered under it. It is thought that it was moved about 8 to 13 miles, from an uncertain location.[7]

Besides his description of the pillar, Führer made a detailed description of the remains of a monumental "Konagamana stupa" near the Nigali Sagar pillar,[8] which was later discovered to be an imaginative construct.[9] Furher wrote that "On all sides around this interesting monument are ruined monasteries, fallen columns, and broken sculptures", when actually nothing can be found around the pillar.[10] In the following years, inspections of the site showed that there were no such archaeological remains, and that, in respect to Fuhrer's description "every word of it is false".[11] It was finally understood in 1901 that Führer had copied almost word-for-word this description from a report by Alexander Cunningham about the stupas in Sanchi.[12]

Kanakamuni Buddha

It is said that in this place the Kanakamuni Buddha, one of the Buddhas of the past, was born.[13] The Asoka inscription engraved on the pillar in Brahmi script and Pali language attests the fact that Emperor Asoka enlarged the Kanakamuni Buddha's stupa, worshiped it and erected a stone pillar for Kanakamuni Buddha on the occasion of the twentieth year of his coronation.

Added to the doubts on the authenticity of the inscription, the very mention of a "divinized Buddha having been several time reborn" and preceded by other Buddhas such as the Kanakamuni Buddha, inscribed on a pillar in a historical period as early as the 3rd century BCE, is considered by some authors as quite doubtfull and problematic.[14] Such complex religious constructions are generally considered as belonging to later stages of the development of Buddhism.[14]

The Nigali Sagar Edict

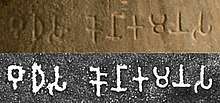

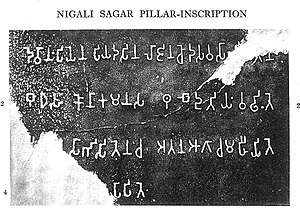

The inscription, made when Emperor Asoka visited the site in 249 BCE and erected the pillar, reads:

| Translation (English) | Transliteration (original Brahmi script) | Inscription (Prakrit in the Brahmi script) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

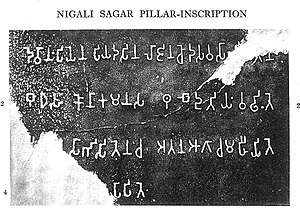

Rubbing of the inscription. |

Because of this dedication by Ashoka, the Nigali Sagar pillar has the earliest known record ever of the word "Stupa" (here the Pali word Thube).[19]

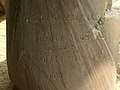

There is also a second inscription, "Om mani padme hum" and "Sri Ripu Malla Chiram Jayatu 1234" made by King Ripu Malla in the year 1234 (Saka Era, corresponding to 1312 CE).

Accounts of the pillar

The Chinese pilgrims Fa-Hien and Hiuen-Tsang describe the Kanakamuni Stupa and the Asoka Pillar in their travel accounts. Hiuen Tsang speaks of a lion capital atop the pillar, now lost.

Gallery

Pillar stump and inscription of Ashoka.

Pillar stump and inscription of Ashoka. Inscription by Ashoka.

Inscription by Ashoka. Rubbing of the inscription.

Rubbing of the inscription. Full length of the pillar.

Full length of the pillar. 13th century inscription by King Ripu Malla.

13th century inscription by King Ripu Malla. Inscription of a bird.

Inscription of a bird. Another general view.

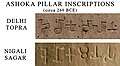

Another general view. Nigali Sagar pillar inscriptions

Nigali Sagar pillar inscriptions Ashoka pillar inscriptions

Ashoka pillar inscriptions Nigali Sagar pillar plan

Nigali Sagar pillar plan

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ashoka Pillar, Nigali Sagar. |

- Smith, Vincent A. (1897). "The Birthplace of Gautama Buddha". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland: 616–617. ISSN 0035-869X. JSTOR 25207888.

- Lumbini development trust report

- "In 1893 a Nepalese officer on a hunting expedition found an Asokan pillar near Nigliva, at Nigali Sagar." Falk, Harry. The discovery of Lumbinī. p. 9.

- Waddell, L. A.; Wylie, H.; Konstam, E. M. (1897). "The Discovery of the Birthplace of the Buddha". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland: 645–646. JSTOR 25207894.

- Thomas, Edward J. (2002). History of Buddhist Thought. Courier Corporation. p. 155, note 1. ISBN 978-0-486-42104-9.

- Führer, Alois Anton (1897). Monograph on Buddha Sakyamuni's birth-place in the Nepalese tarai /. Allahabad : Govt. Press, N.W.P. and Oudh.

- Mukherji, P. C.; Smith, Vincent Arthur (1901). A report on a tour of exploration of the antiquities in the Tarai, Nepal the region of Kapilavastu;. Calcutta, Office of the superintendent of government printing, India.

- Führer, Alois Anton (1897). Monograph on Buddha Sakyamuni's birth-place in the Nepalese tarai /. Allahabad : Govt. Press, N.W.P. and Oudh. p. 22.

- Thomas, Edward Joseph (2000). The Life of Buddha as Legend and History. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-41132-3.

- ""On all sides around this interesting monument are ruined monasteries, fallen columns, and broken sculptures." This elaborate description was not supported by a single drawing, plan, or photograph. Every word of it is false." in Rijal, Babu Krishna; Mukherji, Poorno Chander (1996). 100 Years of Archaeological Research in Lumbini, Kapilavastu & Devadaha. S.K. International Publishing House. p. 58.

- Mukherji, P. C.; Smith, Vincent Arthur (1901). A report on a tour of exploration of the antiquities in the Tarai, Nepal the region of Kapilavastu;. Calcutta, Office of the superintendent of government printing, India. p. 4.

- Falk, Harry. The discovery of Lumbinī. p. 11.

- Political Violence in Ancient India by Upinder Singh p.46

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2017). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. pp. 233–235. ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1.

- Basanta Bidari - 2004 Kapilavastu: the world of Siddhartha - Page 87

- Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 165.

- Basanta Bidari - 2004 Kapilavastu: the world of Siddhartha - Page 87

- Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 165.

- Amaravati: The Art of an early Buddhist Monument in context. p.23

See also

| Edicts of Ashoka (Ruled 269–232 BCE) | |||||

| Regnal years of Ashoka |

Type of Edict (and location of the inscriptions) |

Geographical location | |||

| Year 8 | End of the Kalinga war and conversion to the "Dharma" |  Udegolam Nittur Brahmagiri Jatinga Rajula Mandagiri Yerragudi Sasaram Barabar Kandahar (Greek and Aramaic) Kandahar Khalsi Ai Khanoum (Greek city) | |||

| Year 10[1] | Minor Rock Edicts | Related events: Visit to the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya Construction of the Mahabodhi Temple and Diamond throne in Bodh Gaya Predication throughout India. Dissenssions in the Sangha Third Buddhist Council In Indian language: Sohgaura inscription Erection of the Pillars of Ashoka | |||

| Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription (in Greek and Aramaic, Kandahar) | |||||

| Minor Rock Edicts in Aramaic: Laghman Inscription, Taxila inscription | |||||

| Year 11 and later | Minor Rock Edicts (n°1, n°2 and n°3) (Panguraria, Maski, Palkigundu and Gavimath, Bahapur/Srinivaspuri, Bairat, Ahraura, Gujarra, Sasaram, Rajula Mandagiri, Yerragudi, Udegolam, Nittur, Brahmagiri, Siddapur, Jatinga-Rameshwara) | ||||

| Year 12 and later[1] | Barabar Caves inscriptions | Major Rock Edicts | |||

| Minor Pillar Edicts | Major Rock Edicts in Greek: Edicts n°12-13 (Kandahar) Major Rock Edicts in Indian language: Edicts No.1 ~ No.14 (in Kharoshthi script: Shahbazgarhi, Mansehra Edicts (in Brahmi script: Kalsi, Girnar, Sopara, Sannati, Yerragudi, Delhi Edicts) Major Rock Edicts 1-10, 14, Separate Edicts 1&2: (Dhauli, Jaugada) | ||||

| Schism Edict, Queen's Edict (Sarnath Sanchi Allahabad) Lumbini inscription, Nigali Sagar inscription | |||||

| Year 26, 27 and later[1] |

Major Pillar Edicts | ||||

| In Indian language: Major Pillar Edicts No.1 ~ No.7 (Allahabad pillar Delhi pillar Topra Kalan Rampurva Lauria Nandangarh Lauriya-Araraj Amaravati) Derived inscriptions in Aramaic, on rock: | |||||