Niccolò Cacciatore

Niccolò Cacciatore (Italian: [nikkoˈlɔ kkattʃaˈtoːre]; 26 January 1770 – 28 January 1841) was an Italian astronomer.[1]

Niccolò Cacciatore | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 January 1770 Casteltermini, Italy |

| Died | 28 January 1841 (aged 71) Palermo, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

Cacciatore was born at Casteltermini, in Sicily. While studying mathematics and physics in Palermo, he became acquainted with Giuseppe Piazzi, head of the Palermo Astronomical Observatory, and became a graduate student assistant at the observatory in 1798. Two years later, in 1800, the year before Piazzi discovered Ceres, Cacciatore was formally put on staff.[1]

Cacciatore helped Piazzi compile the second edition of the Palermo Star Catalogue (1814). He did the bulk of the work, in fact heading the project starting in 1807. He also published works on the comets of 1807 and 1819.[1]

Cacciatore succeeded Piazzi as director of the Palermo Observatory in 1817. As such, his most notable observation was the discovery of globular cluster NGC 6541 on 19 March 1826. The observatory was attacked, and he was imprisoned, during the Sicilian Revolution of 1820, but he survived to restore the facility and lead it for two more decades.[1]

In addition to astronomy, he was an expert on meteorology, and wrote a number of books on the subject. Further, after the political troubles of 1820, he served as a member of the legislature of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.[1] Cacciatore was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1837.[2]

He married Emmanuela Martini in 1812, with whom he had five children. His son, Gaetano, succeeded him as director of the observatory.[1]

Sualocin and Rotanev

Alpha and Beta Delphini are a pair of visually unremarkable 4th magnitude stars. When the Palermo Catalogue was published in 1814, the unfamiliar names Sualocin and Rotanev were attached to them. Eventually the Reverend Thomas William Webb, a British astronomer, puzzled out the explanation.[1][3] Cacciatore's name, Nicholas Hunter in English translation, would be Latinized to Nicolaus Venator. Reversing the letters of this construction produces the two star names. They have endured, the result of Cacciatore's little practical joke of naming the two stars after himself. How Webb arrived at this explanation 45 years after the publication of the catalogue is still a mystery.[4] In 2016, the two names were approved as official by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).[5]

Works

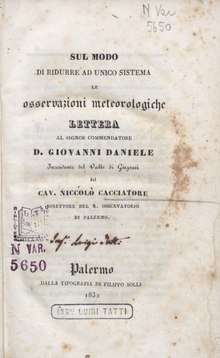

- Cacciatore, Niccolò (1832). Sul modo di ridurre ad unico sistema le osservazioni meteorologiche. Palermo: dalla Tipografia di Filippo Solli.

See also

References

- "Description of a small Observatory at Poonah". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 6: 29–31. 1844. Bibcode:1844MNRAS...6...29.. doi:10.1093/mnras/6.4.25.

- "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter C" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- Webb, T.W. (1859). Celestial Objects for Common Telescopes. London: Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 193–194.

- Hurn, Mark. "Secrets of the 1814 Palermo Star Catalogue". Apollo. Mark Hurn, Institute of Astronomy Library, Univ. of Cambridge. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- "Naming Stars [includes "List of IAU-approved Star Names as of 10 August 2018"]". International Astronomical Union. 10 Aug 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

Further reading

- Cacciatore at NGC/IC observers; includes picture

- For NGC 6541 see Olbers AN #104, "Ein neuer Nebelfleck" AN #113, and Biela AN #120