Neochanna

Neochanna is a genus of galaxiid fishes, commonly known as mudfish, which are native to New Zealand and south-eastern Australia.

| Neochanna | |

|---|---|

| |

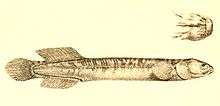

| Brown mudfish, Neochanna apoda | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Neochanna Günther, 1867 |

| species | |

|

See text. | |

Species

The recognized species in this genus are:[1]

- Neochanna apoda Günther, 1867 (brown mudfish)

- Neochanna burrowsius (Phillipps, 1926) (Canterbury mudfish)

- Neochanna cleaveri (Scott, 1934) (Tasmanian mudfish)

- Neochanna diversus Stokell, 1949 (black mudfish)

- Neochanna heleios Ling & Gleeson, 2001 (Northland mudfish)

- Neochanna rekohua (Mitchell, 1995) (Chatham mudfish)

Description

Mudfishes are small, growing to a maximum of 180 mm (7.1 in).[2]:303 They have a tubular, highly flexible, scaleless body with rounded fins, well-developed flanges on the caudal peduncle, tubular nostrils, small or absent pelvic fins, and mottled brown colouration.[3] Adults are active at night and are usually found in the benthic zone, while juveniles are active during the day and are found in open water.[3]

Habitat

Mudfishes are found in wetlands, swamps, drains and springs. They typically live in still or slowly flowing, shallow water, with thick aquatic vegetation and overhead cover.[3]

Aestivation

Mudfish have the ability to aestivate during droughts, seeking out moist areas under logs and vegetation so they do not dry out. While emersed (out of the water), they respire through cutaneous respiration, either through their skin, or by taking mouthfuls of air.[2]:304 Emersed mudfish frequently lie on their backs, possibly improving cutaneous respiration through the thinner abdominal skin, improving oxygenation of vital organs, or rehydrating skin on their upper surfaces.[3]

As wetland habitats dry out, the standing water may become stagnant and hypoxic. During this time mudfish will hang quietly at the surface with bubbles of air in their mouths to improve oxygen absorption.[3] Some choose to leave hypoxic water before it dries out, and leave again if pushed back in.[3]

While emersed they are aware of their surroundings and are responsive to change in their environment: changing position, moving to damper areas, and congregating.[3] Although they may be found deep below the surface in cavities and root holes, they do not appear to create burrows for the purpose of aestivation, with the exception of N. cleaveri.[3] Under experimental drought conditions, N. cleaveri created vertical shafts in the mud substrate, which allowed the fish to remain submersed as the free water evaporated.[4] As the water within the shaft evaporated, the mudfish excavated horizontal tunnels where they awaited the return of the water.[4] They do not feed while emersed, but may return to water at night to feed.[3]

Biogeography

Mudfish species are geographically widely separate, due to a combination of oceanic dispersal, sea-level change, volcanism and glaciation.

Based on anatomical and genetic data, the Tasmanian mudfish is sister to the New Zealand mudfishes.[2]:305 The divergence is too recent for this wide distribution to result from the separation of New Zealand and Australia 83 million years ago.[2]:305 The Tasmanian mudfish is amphidromous, spending its first 2–3 months at sea, and it is likely that this was the means of dispersal to New Zealand. All five of the New Zealand mudfishes have lost this migratory life cycle.[2]:305

Of the New Zealand species, the Canterbury and Chatham mudfishes are the least departed from the ancestral form, retaining small pelvic fins and a more Galaxias-like shape.[5] The Chatham Islands emerged from the sea recently, possibly 2–3 million years ago, so the ancestors of the Chatham mudfish must have retained the amphidromous life cycle until after dispersal to these islands.[2]:305[5]

The Tasmanian mudfish is found in Tasmania and in southern Victoria, on either side of the Bass Strait,[4] and New Zealand's brown mudfish is found on either side of Cook Strait.[2]:305 Both species likely extended their range during the Pleistocene, when the sea levels were low and there were land connections between the respective islands, and were subsequently separated when sea levels rose again.[2]:305[4]

There is a large gap in the brown mudfish distribution in the lower North Island. This is possibly due to the effects of volcanism causing local extinction, and the species was unable to recolonise affected catchments as it has lost the highly mobile amphidromous life cycle.[2]:308 The absence of brown mudfish (or other Neochanna species) from the southern half of the west coast of the South Island is likely due to glaciation in the late Pleistocene, although there has been some range expansion into the glacier-affected areas.[2]:309[3]

The black and Northland mudfishes are the only species with a near-overlapping distribution.[2]:308 The black mudfish is found broadly throughout the northern North Island, surrounding the much smaller distribution of the Northland mudfish, which is only found on the Kerikeri volcanic plateau.[3] It is suggested that the common ancestor of both species was found throughout the northern North Island, but it was divided into two populations by high sea levels during the Pliocene.[2]:307[3] These two populations then separated into the Northland mudfish in the north, and the black mudfish in the south.[6] After sea levels fell again, the black mudfish expanded its range northwards, eventually surrounding that of the Northland mudfish.[3][6]

The Canterbury mudfish is found across the Canterbury Plains, an alluvial plain formed by large and highly mobile braided rivers.[2]:311 The lack of genetic variation or structuring between populations suggests that these mudfish have been reduced to small founder populations, possibly due to droughts.[2]:311 The subsequent range expansion may have been assisted by mobile braided rivers.

References

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). Species of Neochanna in FishBase. February 2012 version.

- McDowall, R.M. (2010). New Zealand Freshwater Fishes: An Historical and Ecological Biogeography. Springer. ISBN 978-90-481-9270-0.

- O'Brien, L; Dunn, N (2007). Mudfish (Neochanna Galaxiidae) literature review. Science for Conservation 277 (PDF). Wellington: Department of Conservation. ISBN 9780478142655.

- Koehn, J.D.; Raadik, T.A. (1991). "The Tasmanian mudfish, Galaxias cleaveri Scott, 1934, in Victoria". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria. 103 (2).

- Waters, J.M.; McDowall, R.M. (2005). "Phylogenetics of the Australasian mudfishes: evolution of an eel-like body plan". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 37 (2): 417–425. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.07.003. PMID 16137896.

- Gleeson, D.M.; Howett, R.L.J.; Ling, N. (1999). "Genetic variation, population structure and cryptic species within the black mudfish, Neochanna diversus, an endemic galaxiid from New Zealand". Molecular Ecology. 8 (1): 47–57. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00528.x.

External links

- "Neochanna". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 1 June 2007.

- New Zealand Mudfishes - a guide. Nick Ling. 2001. Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand.

- "New Zealand mudfish (Neochanna spp.) recovery plan (Northland, black, brown, Canterbury and Chatham mudfish) (Threatened Species Recovery Plan 51)" (PDF). Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. 2003. Retrieved 2007-09-05.