National Christian Forensics and Communications Association

The National Christian Forensics and Communications Association is a speech and debate league for Christian students in the United States. The NCFCA was established in 2001 after outgrowing its parent organization, the Home School Legal Defense Association (HSLDA), which had been running the league since it was originally established in 1995. NCFCA is now organized under its own board of directors with regional and state leadership coordinating various tournaments throughout the season.

Logo of the NCFCA | |

| Formation | 1995[1] |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Mountlake Terrace, Washington, United States [2] |

| Website | www |

Structure of the organization

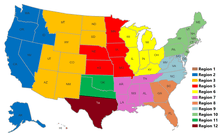

The NCFCA is an entirely volunteer-run, non-profit organization. Tournaments are run by volunteers, who are usually parents, club directors, and league officials in the area. The judging pool includes parents of competitors, NCFCA alumni, and members of the community. Coaches also serve as judges on a volunteer basis. The NCFCA is governed by a board and divided into eleven regions. Each region has a regional coordinator and each state has a representative.

Clubs

As homeschooled debaters do not have "schools" to compete with, the fundamental unit of the NCFCA is the "club." A club is a group of competitors, coaches, and families who meet together to practice, help one another, and organize tournaments.

Regions

The NCFCA is divided into eleven regions. This is known as the Regional System and was adopted during the 2003–2004 season to accommodate the growth of the league. Each region receives a specific number of qualifying slots to nationals, the year-end championship tournament held in a different location each June. The number of slots allotted to the region is determined largely by the number of affiliates in that region. A majority of a region's slots are awarded at a regional championship tournament sometime in April or early May, known as "regionals." The rest are given out on an "at large" basis to the highest performing teams that do not qualify through regionals. In previous years, other methods of dividing slots included giving slots to the states in the region, which then held state championships, or simply dividing the slots up amongst a series of pre-regional tournaments.

The eleven NCFCA regions are:

- Region 1: Hawaii and Canada

- Region 2: Alaska, Idaho, Nevada, California, Oregon, and Washington

- Region 3: Arizona, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, Wyoming, and Colorado

- Region 4: No longer exists. Formerly a region containing all of Texas and Oklahoma, see regions 11 and 12.

- Region 5: Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, and Nebraska

- Region 6: Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin

- Region 7: Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee

- Region 8: Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina

- Region 9: Delaware, Maryland, North Carolina, Virginia, Washington D.C., and West Virginia

- Region 10: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont

- Region 11: Oklahoma and North Texas

- Region 12: South Texas

Starting in the 2015–16 season, and due to the overwhelming size of the student population of specific regions in comparison to other regions around the nation, Region 4 and 8 were split into 'Districts.' Region four's districts sustained their own student populations, leading to the abolition of region four and the creation of regions eleven and twelve in the respective location of each district. Region 8 has since been reunited into one region because of an exponential loss of competitors due to the district split. In the 2019-20 season, Region 2 was split into two districts due to a large increase in competitors. Competitors in region 2 must now affiliate with their district based on geographical location within the region. Each district has separate qualifier tournaments within itself, but combines for the regional tournament in order to divide national slots.

National Opens

Additionally, a certain number of wildcard slots are awarded each year at competitions known as National Opens. Currently, each national open awards two nationals slots for every individual speech event and debate event and four slots for moot court. These are large tournaments held mostly at colleges or large convention centers and are open to the entire nation.[3] Qualifying at a National Open tends to be more difficult than a regional qualifying tournament because of their increased size.

National opens since 2005:

- 2005: California National Open (San Diego, CA); Colorado National Open (Colorado Springs, CO)[4][5]

- 2006: California National Open (San Diego, CA); Tennessee National Open (Jefferson City, TN); Colorado National Open (Colorado Springs, CO)[4][5]

- 2007: Washington National Open (Seattle, WA); Ohio National Open (Cedarville, OH); Texas National Open (Houston, TX)[4][5]

- 2008: Virginia National Open (Virginia Beach, VA); Colorado National Open (Colorado Springs, CO); Texas National Open (Houston, TX)[4][5]

- 2009: Texas National Open (Houston, TX); Alabama National Open (Trussville, AL)[4][5]

- 2010: Texas National Open (Houston, TX); Massachusetts National Open (Wenham, MA); Colorado National Open (Denver, CO)[4]

- 2011: Texas National Open (Houston, TX); Georgia National Open (Lookout Mountain, GA)[4][5]

- 2012: Texas National Open (Houston, TX); Illinois Open (Joliet, IL); Washington Open (Spokane, WA)[4][5]

- 2013: Alabama National Open (Montgomery, AL); Massachusetts National Open (Wenham, MA)[4][5]

- 2014: Idaho National Open (Nampa, ID); Minnesota National Open (St. Paul, MN); North Carolina National Open (Black Mountain, NC)[4][5]

- 2015: North Carolina National Open (Black Mountain, NC); Massachusetts National Open (Wenham, MA); Idaho National Open (Nampa, ID)[6][5]

- 2016: California National Open (San Diego, CA); North Carolina National Open (Black Mountain, NC); Oklahoma National Open (Shawnee, OK); Wisconsin National Open (Oshkosh, WI)[7]

- 2017: Washington National Open (Spokane, WA); Massachusetts National Open (Wenham, MA); and North Carolina National Open (Black Mountain, NC).

- 2018: Wisconsin National Open (Oshkosh, WI) and North Carolina National Open (Black Mountain, NC).

- 2019: North Carolina National Open (Black Mountain, NC).

- 2020: North Carolina National Open (Black Mountain, NC) and Kentucky National Open (Louisville, KY).

National Mixers

National Mixers debuted in the 2017-2018 season. They were officially known as March Mixer, because they only occurred in the month of March. As national level tournaments, they host moot court, but they only give out one national championship slot in each individual event and debate event and two slots in moot court. In the first year, there were eight March Mixers, all occurring in the first two weeks of March. There was a mixer in a city inside every region except 1 and 3 (which are much smaller than the other eight regions). Because of the large number of mixers and their close proximity in time, most competitors went to only the mixer closest to their home in the first year even though they could technically attend any mixer in the country.

Competition

During the 2005–2006 season, there were roughly 5,000 competitors, making the NCFCA the third largest national high school speech and debate league after the National Speech and Debate Association and the National Catholic Forensic League. These competitors vied for 90 policy nationals slots, 49 Lincoln-Douglas slots, and approximately 400 speech slots. Unlike other leagues, however, individuals are not constrained to one event and may compete in one type of debate and up to five speech events. Thus, 550 nationals slots does not necessarily translate to 550 competitors at nationals. Those who qualify to nationals in five IEs are referred to as "marathoners" and those who qualify in five IEs and debate are called "ironmen." Both are recognized at the awards ceremony and in the NCFCA Hall Of Fame. Those who achieve High Speaker points for debate rounds are honored with "speaker awards". Indicating that they spoke well in their rounds compared to the other competitors. For the 2018 national championship, 800 speech slots and 140 total debate slots divided between policy and Lincoln Douglas were awarded.

Individual events

The NCFCA offers ten individual events from three categories: Platform, Interpretation, and Limited Preparation.[8] Platform events are memorized informative speeches written by the speaker. The three current Platform categories are informative, persuasive, and digital presentation. (Informative and Persuasive Speaking were both retired for the 2017–2018 season and later returned in the 2018-2019 season, replacing After Dinner Speaking and Original Oratorical) Interpretation events are memorized performances of published literary works, usually involving acting. The four Interpretive events are Biblical Thematic, Duo Interpretation, Open Interpretation, and humorous (Dramatic Interpretation was retired for the 2011–2012 season.) Limited Preparation events are speeches delivered with two to twenty minutes of preparation. Limited Prep speech topics are randomly assigned to competitors at their turn. The three NCFCA Limited Preparation events are Apologetics, Extemporaneous Speaking, and Impromptu Speaking.

From 2002–2007 and 2013–2014, the NCFCA also provided a different Wildcard event each season:

- The 2002–2003 Wildcard was Duo Impromptu. Two competitors would randomly draw three pieces of paper with the words for a person, place, and thing. Then they would have four minutes to prepare a five-minute skit incorporating all three nouns.

- The 2003–2004 Wildcard was Impromptu Apologetics. It was later renamed Apologetics and has become a standard NCFCA event.

- The 2004–2005 Wildcard was Oratorical Interpretation. The competitor would interpret a famous and/or historical speech.

- The 2006–2007 Wildcard was Thematic Interpretation. Competitors select several pieces of literature and weave them around a common theme. Thematic interpretation became a standard event for the 2009–2010 and 2010–2011 seasons but was retired in July 2011, and became a standard event again for the 2013–2014 season.

- From 2007–2012, there were no new Wildcard events.

- The 2013–2014 Wildcard was After-Dinner Speaking, a sort of humorous, persuasive or informative speech.[9]

Debate

The NCFCA offers two types of debate — Team Policy Debate and Lincoln-Douglas Value Debate.[10] As the purpose of the NCFCA is to train good communicators, not just good debaters,[11] the use of overly complicated theory and extremely fast talking (also known as "speed and spread") is discouraged.[12] This is accomplished through the judging paradigm. Tournaments employ a mixed pool of judges, but are mostly made up of lay judges. NCFCA debaters are therefore forced to communicate to all levels of judges.

Debate resolutions

NCFCA resolutions are chosen annually by affiliate families through a voting process. Each family is allowed one vote per each style of debate.

Team Policy Resolutions

2020-2021: Resolved: The European Union should substantially reform its immigration policy.

2019-2020: Resolved: The United States Federal Government should substantially reform its energy policy.

2018-2019: Resolved: The United States Federal Government should substantially reform its foreign policy regarding international terrorism.

2017-2018: Resolved: The United States should significantly reform its policies regarding higher education.

2016-2017: Resolved: The United States Federal Government should substantially reform its policies toward the People's Republic of China.

2015–2016: Resolved: That the United States Federal Court system should be significantly reformed.[13]

2014–2015: Resolved: The United States should significantly reform its policy toward one or more countries in the Middle East.[13]

2013–2014: Resolved: That federal election law should be significantly reformed in the United States.[13]

2012–2013: Resolved: The United Nations should be significantly reformed or abolished.[14]

2011–2012: Resolved: The United States Federal Government should significantly reform its criminal justice system.[14]

2010–2011: Resolved: That the United States Federal Government should significantly reform its policy toward Russia.[14]

2009–2010: Resolved: That the United States Federal Government should significantly reform its environmental policy.[14]

2008–2009: Resolved: That the United States Federal Government should significantly change its policy toward India.[14]

2007–2008: Resolved: That the United States Federal Government should substantially change its policy on illegal immigration.[14]

2006–2007: Resolved: That the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) should be significantly reformed or abolished.[14]

2005–2006: Resolved: That medical malpractice law should be significantly reformed in the United States.[14]

2004–2005: Resolved: That the United States should change its energy policy to substantially reduce its dependence on foreign oil.[14]

2003–2004: Resolved: That the United States federal government should significantly change its policy toward one or more of its protectorates.[14]

2002–2003: Resolved: That the United States should significantly change its trade policy within one or more of the following areas: The Middle East and Africa.[14]

2001–2002: Resolved: That the United States federal government should significantly change its agricultural policy.[14]

2000–2001: Resolved: That the United States should significantly change its immigration policy.[14]

1999–2000: Resolved: That the Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution should be repealed and replaced with an alternate tax policy.[14]

1998–1999: Resolved: That the United States federal government should substantially change the rules governing federal campaign finances.[14]

1997–1998: Resolved: That Congress should enact laws which discourage the relocation of U.S. businesses to foreign countries.[14]

1997–1998: Resolved: That the United States should change its rules governing foreign military intervention.[14]

Lincoln Douglas Resolutions

2020-2021: Resolved: In democratic elections, the public's right to know ought to be valued above a candidate's right to privacy.

2019-2020: Resolved: Preventive war is ethical.

2018-2019: Resolved: When in conflict, governments should value fair trade above free trade.

2017–2018: Resolved: Nationalism ought to be valued above globalism.

2016–2017: Resolved: Rehabilitation ought to be valued above retribution in criminal justice systems.

2015–2016: Resolved: When in conflict, the right to individual privacy is more important than national security.[13]

2014–2015: Resolved: In the realm of economics, freedom ought to be valued above equity.[13]

2013–2014: Resolved: National security ought to be valued above Freedom of the press.[13]

2012–2013: Resolved: That governments have a moral obligation to assist other nations in need.[14]

2011–2012: Resolved: In the pursuit of justice, due process ought to be valued above the discovery of fact.[14]

2010–2011: Resolved: A government's legitimacy is determined more by its respect for popular sovereignty than individual rights.[14]

2009–2010: Resolved: That competition is superior to cooperation as a means of achieving excellence.[14]

2008–2009: Resolved: When in conflict, idealism ought to be valued above pragmatism.[14]

2007–2008: Resolved: That the United States of America ought to more highly value isolationism.[14]

2006–2007: Resolved: Democracy is overvalued by the United States government.[14]

2005–2006: Resolved: That the media's right to protect confidential sources is more important than the public's right to know.[14]

2004–2005: Resolved: That the restriction of civil rights for the sake of national security is justified.[14]

2003–2004: Resolved: That when in conflict, cultural unity in the United States should be valued above cultural diversity.[14]

2002–2003: Resolved: That human rights should be valued above national sovereignty.[14]

2001–2002: Resolved: That the restriction of economic liberty for the sake of the general welfare is justified in the field of agriculture.[14]

Moot Court

Starting in the 2016-2017 season, the NCFCA began offering moot court, but only at national level tournaments. For 2016-2017, this meant only at national opens, but for 2017-2018 they were also offered at the National Mixer/ Mini-Open Tournaments. In moot court, two teams of two students deliver oral arguments before a panel of "judges" similar to a United States Supreme Court or Appellate Court. They cite case law in order to convince the judges that a fictional court decision developed by the NCFCA should or should not be overturned.

National Championship locations

- 1998: Home School Legal Defense Association – Purcellville, Virginia

- 1999: Home School Legal Defense Association – Purcellville, Virginia

- 2000: Point Loma Nazarene University – San Diego, California

- 2001: Santa Clara University – Santa Clara, California

- 2002: Blackman High School – Murfreesboro, Tennessee

- 2003: Cedarville University – Cedarville, Ohio

- 2004: Liberty University – Lynchburg, Virginia

- 2005: Point Loma Nazarene University – San Diego, California

- 2006: Patrick Henry College – Purcellville, Virginia

- 2007: University of Mary Hardin-Baylor – Belton, Texas

- 2008: Berry Middle School – Birmingham, Alabama

- 2009: Bob Jones University – Greenville, South Carolina

- 2010: Regent University – Virginia Beach, Virginia

- 2011: Gordon College – Wenham, Massachusetts

- 2012: Northwestern College – St. Paul, Minnesota

- 2013: Oral Roberts University – Tulsa, Oklahoma

- 2014: Patrick Henry College – Purcellville, Virginia

- 2015: Northwestern College – St. Paul, Minnesota

- 2016: Oklahoma Baptist University – Shawnee, OK

- 2017: Northwestern College – St. Paul, Minnesota

- 2018: Northwestern College – St. Paul, Minnesota

- 2019: Anderson University - Anderson, South Carolina

- 2020: Northwestern College – St. Paul, Minnesota (the 2020 national championship was canceled due to COVID-19 concerns)[15]

See also

- National Forensic League

- National Catholic Forensic League

- Stoa USA

References

- "Global Debate Blog". Debate.uvm.edu. 2007-06-12. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- Archived April 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Rhetoric team to participate in Texas National Open Tournament". Huntsville Item. 2 March 2008.

- Archived November 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "Past Seasons' Results". NCFCA. Archived from the original on 2016-06-08. Retrieved 2016-05-13.

- "Current Season's Results". NCFCA. Archived from the original on 2016-04-27. Retrieved 2016-05-13.

- "Competition Results". Ncfca.org. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- "Speech and Debate Competition". Ncfca.org. Archived from the original on 2014-07-29. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- Ida Brown (9 January 2008). "Home schoolers from four states to debate at local church". Meridian Star.

- Archived April 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Archived April 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Debate". NCFCA.org. Archived from the original on 2014-09-08. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- "Past Debate Resolutions". Ncfca.org. Archived from the original on 2014-07-30. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- https://www.ncfca.org/ncfca-season-cancellation-notice/