Nafplio

Nafplio (Greek: Ναύπλιο, Nauplio or Nauplion in Italian and other Western European languages) is a seaport town in the Peloponnese in Greece that has expanded up the hillsides near the north end of the Argolic Gulf. The town was an important seaport held under a succession of royal houses in the Middle Ages as part of the lordship of Argos and Nauplia, held initially by the de la Roche following the Fourth Crusade before coming under the Republic of Venice and, lastly, the Ottoman Empire. The town was the capital of the First Hellenic Republic and of the Kingdom of Greece, from the start of the Greek Revolution in 1821 until 1834. Nafplio is now the capital of the regional unit of Argolis.

Nafplio Ναύπλιο | |

|---|---|

View of the old part of the city of Nafplio from Palamidi castle. | |

Flag | |

Nafplio Location within the region  | |

| Coordinates: 37°34′N 22°48′E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Peloponnese |

| Regional unit | Argolis |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Dimitris Kostouros |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 390.2 km2 (150.7 sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 33.62 km2 (12.98 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 10 m (30 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipality | 33,356 |

| • Municipality density | 85/km2 (220/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 18,910 |

| • Municipal unit density | 560/km2 (1,500/sq mi) |

| Community | |

| • Population | 14,203 (2011) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 211 00 |

| Area code(s) | 2752 |

| Vehicle registration | ΑΡ |

| Website | www.nafplio.gr |

Name

The name of the town changed several times over the centuries. The modern Greek name of the town is Nafplio (Ναύπλιο).[2] In modern English, the most frequently used forms are Nauplia and Navplion.[3]

In Classical Antiquity, it was known as Nauplia (Ναυπλία) in Attic Greek[4][5][6][7] and Naupliē (Ναυπλίη) in Ionian Greek.[4] In Latin, it was called Nauplia.[8]

During the Middle Ages, several variants were used in Byzantine Greek, including Náfplion (Ναύπλιον), Anáplion (Ἀνάπλιον), and Anáplia (Ἀνάπλια).[7]

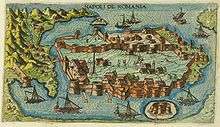

During the Late Middle Ages and early modern period, under Venetian domination, the town was known in Italian as Napoli di Romania, after the medieval usage of "Romania" to refer to the lands of the Byzantine Empire, and to distinguish it from Napoli (Naples) in Italy.

Also during the early modern period, but this time under Ottoman rule, the Turkish name of the town was Mora Yenişehir, after Morea, a medieval name for the Peloponnese, and "yeni şehir", the Turkish term for "new city" (apparently a translation from the Greek Νεάπολη, Italian Napoli). The Ottomans also called it Anabolı.

In the 19th century and early 20th century, the town was called indiscriminately Náfplion (Ναύπλιον) and Nafplio (Ναύπλιο) in modern Greek. Both forms were used in official documents and travel guides. This explains why the old form Náfplion (sometimes transliterated to Navplion) still occasionally survives up to this day.

Geography

Nafplio is situated on the Argolic Gulf in the northeast Peloponnese. Most of the old town is on a peninsula jutting into the gulf; this peninsula forms a naturally protected bay that is enhanced by the addition of man-made moles. Originally almost isolated by marshes, deliberate landfill projects, primarily since the 1970s, have nearly doubled the land area of the city.

Municipality

The municipality Nafplio was formed at the 2011 local government reform by the merger of the following 4 former municipalities, that became municipal units:[9]

- Asini

- Midea

- Nafplio

- Nea Tiryntha

The municipality has an area of 390.241 km2, the municipal unit 33.619 km2.[10]

Population

| Year | Community | Municipal unit | Municipality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 10,611 | - | - |

| 1991 | 11,897 | 14,740 | - |

| 2001 | 13,822 | 16,885 | - |

| 2011 | 14,203 | 18,910 | 33,356 |

History

Mythical origins and Classical antiquity

The area surrounding Nafplio has been inhabited since ancient times, but few signs of this, aside from the walls of the Acronauplia, remain visible. The town has been a stronghold on several occasions during Classical Antiquity. It seems to be mentioned on an Egyptian funerary inscription of Amenophis III as Nuplija.[11] Nauplia (Ancient Greek: ἡ Ναυπλία) was the port of Argos, in ancient Argolis. It was situated upon a rocky peninsula, connected with the mainland by a narrow isthmus. It was a very ancient place, and is said to have derived its name from Nauplius, the son of Poseidon and Amymone, and the father of Palamedes, though it more probably owed its name, as Strabo has observed, to its harbour.[12][13] Pausanias tells us that the Nauplians were Egyptians belonging to the colony which Danaus brought to Argos;[14] and from the position of their city upon a promontory running out into the sea, which is quite different from the site of the earlier Grecian cities, it is not improbable that it was originally a settlement made by strangers from the East.[15] Nauplia was at first independent of Argos, and a member of the maritime confederacy which held its meetings in the island of Calaureia.[16] About the time of the Second Messenian War, it was conquered by the Argives; and the Lacedaemonians gave to its expelled citizens the town of Methone in Messenia, where they continued to reside even after the restoration of the Messenian state by the Theban general Epaminondas.[17] Argos now took the place of Nauplia in the Calaureian confederacy; and from this time Nauplia appears in history only as the seaport of Argos.[18] As such it is mentioned by Strabo,[16] but in the time of Pausanias (2nd century) the place was deserted. Pausanias noticed the ruins of the walls of a temple of Poseidon, certain forts, and a fountain named Canathus, by washing in which Hera was said to have renewed her virginity every year.[19]

Byzantine and Frankish rule

The Acronauplia has walls dating from pre-classical times. Subsequently, Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Turks added to the fortifications. In the middle ages Nauplia was called τὸ Ναύπλιον, τὸ Ἀνάπλιον, or τὰ Ἀνάπλια. It became a place of considerable importance in the middle ages, and has continued so down to the present day. In the time of the Crusades it first emerges from obscurity. Nafplio was taken in 1212 by French crusaders of the Principality of Achaea. It became part of the lordship of Argos and Nauplia, which in 1388 was sold to the Republic of Venice,[20] who regarded it as one of their most important places in the Levant. During the subsequent 150 years, the lower city was expanded and fortified, and new fortifications added to Acronauplia.[21]

Venetian and Ottoman rule

The city, under Venetian rule twice repelled Ottoman attacks and sieges, first by Mehmed the Conqueror during the Ottoman–Venetian War (1463–79) and then by Suleiman the Magnificent. The city surrendered to the Ottomans in 1540, who renamed it Mora Yenişehri and established it as the seat of a sanjak. At that period, Nafplio looked very much like the 16th century image shown below to the right.

The Venetians retook Nafplio in 1685 and made it the capital of their "Kingdom of the Morea". The city was strengthened by building the castle of Palamidi, which was in fact the last major construction of the Venetian empire overseas. However, only 80 soldiers were assigned to defend the city and it was easily retaken by the Ottomans in 1715. Palamidi is located on a hill north of the old town. During the Greek War of Independence, it played a major role. It was captured by forces of Staikopoulos and Kolokotronis in November 1822.

19th century: Independence and first capital

During the Greek War of Independence, Nafplio was a major Ottoman stronghold and was besieged for more than a year. The town finally surrendered on account of forced starvation. After its capture, because of its strong fortifications, it became the seat of the provisional government of Greece.

Count Ioannis Kapodistrias, first head of state of newly liberated Greece, set foot on the Greek mainland for the first time in Nafplio on 7 January 1828 and made it the official capital of Greece in 1829. He was assassinated on 9 October 1831 by members of the Mavromichalis family, on the steps of the church of Saint Spyridon in Nafplio. After his assassination, a period of anarchy followed, until the arrival of King Otto and the establishment of the new Kingdom of Greece. Nafplio remained the capital of the kingdom until 1834, when King Otto decided to move the capital to Athens.

20th and 21st centuries

Tourism emerged slowly in the 1960s, but not to the same degree as some other Greek areas. Nevertheless, it tends to attract a number of tourists from Germany and the Scandinavian countries in particular. Nafplio enjoys a very sunny and mild climate, even by Greek standards, and as a consequence has become a popular day or weekend road-trip destination for Athenians in wintertime.

Nafplio is a port, with fishing and transport ongoing, although the primary source of local employment currently is tourism, with two beaches on the other side of the peninsula from the main body of the town and a large amount of local accommodation.

The building of the National Bank of Greece is probably the only example to have been built in the Mycenaean Revival architectural style.[22]

Transportation

Bus

Since 1952, the town has been served by public bus (KTEL Argolida), which provides daily services to all destinations in region as well as other major Greek centers such as Athens.[23][24] The journey to Athens takes two to two hours and 20 minutes, going via Corinth/Isthmos and Argos.[25]

Rail

Rail service began in 1886 using an earlier station that still stands.[26]

The town is connected by a branch line of ten kilometers from Argos to Nafplio. In 2011, the Corinth–Tripoli–Nafplio train service was suspended during the Greek financial crisis. There was a plan to re-open the line as an extension of the suburban railway that connects Corinth with Athens, but that has not happened.[27]

Architecture and urban sculpture

Acronauplia is the oldest part of the city though a modern hotel has been built on it. Until the thirteenth century, it was a town on its own. The arrival of the Venetians and the Franks transformed it into part of the town fortifications. Other fortifications of the city include the Palamidi and Bourtzi, which is located in the middle of the harbour.

Nafplio maintains a traditional architectural style with many traditional-style colourful buildings and houses, influenced by the Venetians, because of the domination of 1338–1540. Also, modern-era neoclassical buildings are also preserved, while the building of the National Bank of Greece is an example of Mycenaean Revival architecture.

It is one of the few Greek cities not affected by the laws of antiparochí (which demolished old mansions all over Greece), also with efforts of the archaeologist Evangelia Protonotariou Deilaki, even against local interests,[28] preserving so, much of its architectural heritage.

Around the city can be found several sculptures and statues. They are related mostly with the modern history of Nafplio, such as the statues of Ioannis Kapodistrias, Otto of Greece and Theodoros Kolokotronis.

Quarters

Culture

Cuisine

Local specialities include:

- Goglies (Goges), pasta

- Striftades, hand made pasta

- Giosa, lamb or goat meat

- Bogana, lamb meat with potatoes

Notable people

- Nicolas "the Greek" (fl. 1519–1522), one of the 18 survivors of the expedition that completed the first circumnavigation of the world on the Victoria in 1519–1522

- Tellos Agras (1880–1907), fighter in the Greek Struggle for Macedonia

- Leonidas Drosis, sculptor

- Nina Bawden (1925–2012), writer (resident)

- Timoleon Filimon, politician

- Austen Kark (1926–2002), managing director of the BBC World Service (resident)

- Nikos Karouzos (1926–1990), poet

- Vangelis Kazan (1936–2008), actor

- Sotirios Sotiropoulos (1831–1898), lawyer, politician and former Prime Minister of Greece

- Angelos Terzakis (1907–1979), writer

- Charilaos Trikoupis (1832–1896), Prime Minister of Greece seven times from 1875 until 1895

- Panagiotis Tachtsidis (born 1991), football player currently playing in Italian Serie A for Cagliari Calcio

- Emmanouil Zymvrakakis (1861–1928), Greek general of World War I

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Nafplio is twinned with:

Sports

- Pannafpliakos F.C., football

Gallery

.jpg) Byzantine church (12th century)

Byzantine church (12th century) Monument for the Morea Expedition, Philellinon Square

Monument for the Morea Expedition, Philellinon Square.jpg) View of Acronauplia

View of Acronauplia Clock tower in Acronauplia

Clock tower in Acronauplia- View from Palamidi

- The building of National Bank of Greece (example of Mycenaean Revival architecture)

Trion Navarchon (Three admirals) Square with the monument to Demetrius Ypsilantis

Trion Navarchon (Three admirals) Square with the monument to Demetrius Ypsilantis The church of Saint Nicholas

The church of Saint Nicholas St. George Church

St. George Church Othonos Street

Othonos Street St Spyridon church, where Ioannis Kapodistrias was murdered

St Spyridon church, where Ioannis Kapodistrias was murdered- Street of Nafplio

See also

- History of Greece

- Politics of Greece

- List of traditional Greek place names

References

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- « ΑΡΓΟΛΙΚΗ ΑΡΧΕΙΑΚΗ ΒΙΒΛΙΟΘΗΚΗ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑΣ ΚΑΙ ΠΟΛΙΤΙΣΜΟΥ. "Ναύπλιον – Ετυμολογία του Ονόματος". Argolikivivliothiki.gr. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- See Merriam-Webster's (1993), p. 1495.

- See Liddell and Scott revised by Jones (1940), Ναυπλία. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- See Liddell and Scott (1889), Ναυπλία. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- See Bailly (1901), p. 585, Ναυπλία. Retrieved 2013-07-03.

- See Smith (1854), NAU´PLIA. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- Entick, John (2007-11-20). Entick's English-Latin dictionary. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- Kallikratis law Greece Ministry of Interior (in Greek)

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece.

- See Latacz (2004), p. 131.

- ἀπὸ τοῦ ταῖς ναυσὶ προσπλεῖσθαι, Strabo. Geographica. viii. p.368. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 2.38.2.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 4.35.2.

-

- Strabo. Geographica. viii. p.374. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 4.24.4. , 4.27.8, 4.35.2.

- ὁ Ναύπλιος λίμην, Euripides Orest. 767; λιμένες Ναύπλιοι, Electr. 451.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 2.38.2.

- Diplomatarium No. 127.

- Wright, Ch. 1.

- "Greece At Its Most Greek," by Phyllis rose, September 10, 2000, New York Times.

- "Company". K.T.E.L Argolidas. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- "Transportation Means". Municipality of Nafplion. Municipality of Nafplion. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- "Map/Transport". Visit Nafplio. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- "The historical railway station of Nafplio". TrainOSE. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- Zikakou, Ioanna (October 13, 2014). "Hellenic Railway to Reach Nafplio". Greek Reporter. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- Πώς σώθηκε το Ναύπλιο

- Faculties and Departments. University of Peloponnese website. www.uop.gr.

- (in Greek) Study Plan. University of Peloponnese, Department of Theater Studies website.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2011-02-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Twinnings" (PDF). Central Union of Municipalities & Communities of Greece. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

- "Royal city of Cetinje". Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Office du tourisme de Menton". Archived from the original on 2013-09-23. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Niles Sister Cities". Official website. The Village of Niles. 2010. Archived from the original on 2009-03-22. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- "City council minutes" (PDF). Royan city hall. 2005-06-02. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-23. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

![]()

Sources

- Bailly, Anatole (1901), Abrégé du dictionnaire grec-français, Paris, France: Hachette.

- Entick, John. A Compendious Dictionary of the English and Latin Tongues. New edition carefully revised and augmented throughout by Rev. M.G. Sarjant. London, 1825. ()

- Ellingham, Mark; Dubin, Marc; Jansz, Natania; and Fisher, John (1995). Greece, the Rough Guide. Rough Guides. ISBN 1-85828-131-8.

- Gerola, Giuseppe (1930–31). “Le fortificazioni di Napoli di Romania,” Annuario dell regia scuola archeologicca di Atene e delle missioni italiane in oriente 22-24. pp. 346–410.

- Gregory, Timothy E. (1983). Nauplion. Athens.

- Karouzos, Semnes (1979). To Nauplio. Athens.

- Kolokotrones, Theodoros (1969). Memoirs from the Greek War of Independence, 1821-1833. E. M. Edmunds, trans. Originally printed as Kolokotrones: The Klepht and the Warrior. Sixty Years of Peril and Daring. An Autobiography. London, 1892; reprint, Chicago.

- Lamprynides, Michael G. (1898). Ê Nauplia. Athens, reprint 1950.

- Latacz, Joachim (2004), Troy and Homer: Towards the Solution of an Old Mystery, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1889), An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon, Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940), A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented by Sir Henry Stuart Jones, Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Luttrell, Anthony (1966), "The Latins of Argos and Nauplia: 1311-1394", Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 34, pp. 34–55.

- McCulloch, J. R. (1866). "A Dictionary, Geographical, Statistical, and Historical of the Various Countries, Places, and Principal Natural Objects in the World". New edition carefully revised. Longmans, Green, and Co., London, UK. p. 457. ()

- Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (10th ed.), Springfield, Mass., USA: Merriam-Webster, 1993.

- Schaefer, Wulf (1961). "Neue Untersuchungen über die Baugeschichte Nauplias im Mittelalter," Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Vol. 76, pp. 156–214.

- Smith, William, ed. (1854), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854), London, UK: Walton and Maberly.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nafplion. |

- Municipality of Nafplio Official Website

- GTP - Nafplio municipality

- Historical images, poetry

- Nafplio City

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Nafplion. |