Natchez revolt

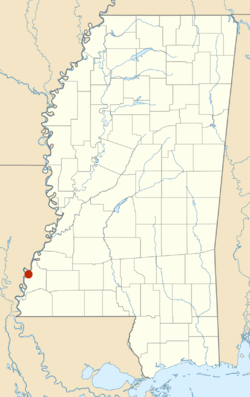

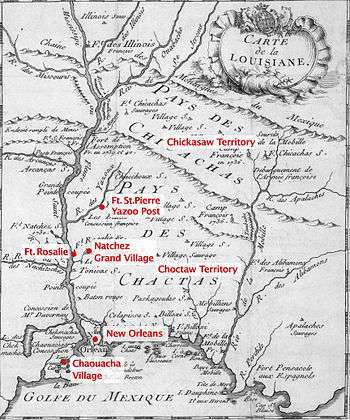

The Natchez revolt, or the Natchez massacre, was an attack by the Natchez people on French colonists near present-day Natchez, Mississippi, on November 29, 1729. The Natchez and French had lived alongside each other in the Louisiana colony for more than a decade prior to the incident, mostly conducting peaceful trade and occasionally intermarrying. After a period of deteriorating relations, however, Natchez leaders were provoked to revolt when the French colonial commandant, Sieur de Chépart, demanded land from a Natchez village for his own plantation near Fort Rosalie. They plotted their attack over several days and managed to conceal their plans from most of the French; those who overheard and warned Chépart of an attack were considered untruthful and were punished. In a coordinated attack on the fort and the homesteads, the Natchez killed almost all of the Frenchmen, while sparing most of the women and African slaves. Approximately 230 colonists were killed overall, and the fort and homes were burned to the ground.

When the French in New Orleans, the colonial capital, heard the news of the massacre, they feared a general Indian uprising and were concerned that the Natchez might have conspired with other tribes. They first responded by ordering a massacre of the Chaouacha people, who had no relation to the Natchez revolt, wiping out their entire village. The French and their Choctaw allies then retaliated against the Natchez villages, capturing hundreds of Natchez and selling them into slavery, although many managed to escape to the north and take refuge among the Chickasaw people. The Natchez waged low-intensity warfare against the French over the following years, but retaliatory expeditions against Natchez refugees among the Chickasaw in 1730 and 1731 forced them to move on and live as refugees among the Creek and Cherokee tribes. By 1736 the Natchez had ceased to exist as an independent people.

The attack on Fort Rosalie destroyed some of the Louisiana colony's most productive farms and endangered shipments of food and trade goods on the Mississippi River. As a result, the French state returned control of Louisiana from the Company of the Indies to the crown in 1731, as the company had been having trouble running the colony. Louisiana governor Étienne Périer was held responsible for the massacre and its aftermath, and he was recalled to France in 1732.

Background

While descending the Mississippi River in 1682, Robert de La Salle became the first Frenchman to encounter the Natchez and declared them an ally. The Natchez were sedentary and lived in nine semi-autonomous villages; the French considered them the most civilized tribe of the region. By 1700 the Natchez' numbers had been reduced to about 3,500 by the diseases that ravaged indigenous populations in the wake of contact with Europeans, and by 1720 further epidemics had halved that population.[1] Their society was strictly divided into a noble class called "the Suns" (Natchez: ʔuwahʃiːɫ) and a commoner class called in French "the Stinkards" (Natchez: miʃmiʃkipih).[2] Between 1699 and 1702, the Natchez received the explorer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville in peace and allowed a French missionary to settle among them. At this time, the Natchez were at war with the Chickasaw people, who had received guns from their English allies, and the Natchez expected to benefit similarly from their relation with the French. Nonetheless, the British presence in the territory led the Natchez to split into pro-British and pro-French factions.[3] The central village, called Natchez or the Grand Village, was led by the paramount chief Great Sun (Natchez: ʔuwahʃiːɫ liːkip[2]) and the war chief Tattooed Serpent (Serpent Piqué in the French sources, Natchez obalalkabiche[4]), both of whom were interested in pursuing an alliance with the French.[5][6]

First, Second and Third Natchez Wars

The first conflict between the French and the Natchez took place in 1716, when the Governor of Louisiana, Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac, passed through Natchez territory and neglected to renew the alliance with the Natchez by smoking the peace calumet. The Natchez reacted to this slight by killing four French traders. Cadillac sent his lieutenant Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville to punish the Natchez. He deceived the Natchez leaders by inviting them to attend a parley, where he ambushed and captured them, and forced the Natchez to exchange their leaders for the culprits who had attacked the French. A number of random Natchez from the pro-British villages were executed. This caused French–Natchez relations to further deteriorate.[7][8] As part of the terms of the peace accord following this First Natchez War, the Natchez promised to supply labor and materials for the construction of a fort for the French. The fort was named Fort Rosalie, and it was aimed at protecting the French trade monopoly in the region from British incursions.[7]

By 1717, French colonists had established the fort and a trading post in what is now Natchez, Mississippi. They also granted numerous concessions for large plantations, as well as smaller farms, on land acquired from the Natchez. Relations between Natchez and colonists were generally friendly—some Frenchmen even married and had children with Natchez women—but there were tensions. There were reports of colonists abusing Natchez, forcing them to provide labor or goods, and as more colonists arrived, their concessions gradually encroached on Natchez lands.[9][10][11]

From 1722 to 1724, brief armed conflicts between the Natchez and French were settled through negotiations between Louisiana governor Bienville and Natchez war chief Tattooed Serpent. In 1723, Bienville had been informed that some Natchez had harassed villagers, and he razed the Natchez village of White Apple and enslaved several villagers, only to discover that the alleged harassment had been faked by the colonists to frame the Natchez.[12] One of the later skirmishes in 1724 consisted of the murder of a Natchez chief's son by a colonist, to which the Natchez responded by killing another Frenchman named Guenot. Bienville then sent French soldiers from New Orleans to attack the Natchez at their fields and settlements, and the Natchez surrendered. Their plea for peace was met following the execution of one of their chiefs by the French.[10]

Chronicler Le Page du Pratz, who lived among the Natchez and was a close friend of Tattooed Serpent, records that he once asked his friend why the Natchez were resentful towards the French. Tattooed Serpent answered that the French seemed to have "two hearts, a good one today, and tomorrow a bad one",[9] and proceeded to tell how Natchez life had been better before the French arrived. He finished by saying, "Before the arrival of the French we lived like men who can be satisfied with what they have, whereas today we live like slaves, who are not suffered to do as they please."[9] The most faithful ally of the French, Tattooed Serpent died in 1725, another blow to the relations between the Natchez and the colonists.[13]

According to archaeologist Karl Lorenz, who excavated several Natchez settlements, another factor that complicated relations between the Natchez and the colonists was the fact that the French did not well understand the Natchez political structure. The French assumed that the Great Sun, the chief of the Grand Village, also held sway over all the other Natchez villages. In truth, each village was semi-autonomous, and the Great Sun's power only extended to the villages of Flour and Tioux (with which the Grand Village was allied) and not to the three pro-British villages of White Apple, Jenzenaque and Grigra. When the Great Sun died in 1728 and was succeeded by his inexperienced nephew, the pro-British villages became more powerful than the pro-French villages centered at Natchez.[14]

Commandant Chépart

In 1728, Sieur de Chépart (also known as Etcheparre and Chopart), whom Governor Étienne Périer had recently appointed as commandant of Fort Rosalie, was brought to New Orleans and put on trial before the governor for abuse of power, specifically behavior toward the Natchez that was unpopular among the French. Chépart was saved from punishment, however, by "the interference of influential friends",[15] and upon returning to the fort, he continued to administer it as he had before.[15] Chépart told the Natchez that November that he wished to seize land for a plantation in the center of White Apple, where the Natchez had a temple of their people's graves.[16][17][18] Governor Périer sided with Chépart and planted a cross on the land he sought.[11] By this point, most of the colonists disapproved of Chépart's actions, including Jean-François-Benjamin Dumont de Montigny, a French historian who wrote that Chépart's demand marked the first time that a French colonial leader had simply claimed Natchez land as his own, without prior negotiations.[11][18]

When the Natchez began to protest the seizure of their land for the plantation, Chépart said he would burn down the temple that contained their ancestors' graves. In response to this threat, the Natchez seemed to promise to cede the land, wrote Dumont de Montigny, but only if they were given two months to relocate their temple and graves. Chépart agreed to give them the time in exchange for pelts, oil, poultry, and grain—a request the Natchez promised to fulfill later.[11]

Attack

The Natchez then began to prepare for a strike on the French at Fort Rosalie, borrowing firearms from some French colonists with promises to go hunting and to share the game with the guns' owners. Some French men and women overheard the Natchez planning such an attack. According to Le Page du Pratz, it was the Natchez female chief Tattooed Arm who attempted to alert the French of an upcoming attack led by her rivals at White Apple.[19][20] When colonists told Chépart, he disregarded them and placed some in irons on the night before the massacre, when he was drunk.[21][22][23]

On the morning of November 29, 1729, the Natchez came to Chépart with corn, poultry, and deerskins, also carrying with them a calumet—well known as a peace symbol. The commandant, still somewhat intoxicated from drinking the night before, was certain that the Natchez had no violent intentions, and he challenged those who had warned of an attack to prove that the rumors were accurate.[24][25]

While Chépart was accepting the goods, the Natchez started firing, giving the signal for a coordinated attack on Fort Rosalie and on the outlying farms and concessions in the area now covered by the city of Natchez. Chépart ran to call his soldiers to arms, but they had already been killed. The details of the attack are mostly unknown, as chroniclers such as Le Page du Pratz, who talked with several eyewitnesses, stated that the events were "simply too horrific" to recount.[26]

The Natchez had prepared by seizing the galley of the Company of the Indies anchored on the river, so that no Frenchmen could board it and attempt to escape. They had also stationed warriors on the other side of the river to intercept those who might flee in that direction.[27] The commandant at the Yazoo trading post of Fort St. Pierre, Monsieur du Codère, was visiting Fort Rosalie with a Jesuit priest when they heard gunshots. They turned around to return to their ship, but warriors caught up with them, killing and scalping them.[28][29]

The Natchez killed almost all of the 150 Frenchmen at Fort Rosalie, and only about 20 managed to escape.[30] Most of the dead were unarmed. Women, children, and African slaves were mostly spared; many were locked inside a house on the bluff, guarded by several warriors, from where they could see the events.[31] According to Dumont de Montigny's account of the attack, women seen defending their husbands from the violence, or trying to avenge them, were taken captive or killed. One woman's unborn baby was reportedly torn from her before she herself was killed.[32] A year after the event, the tally of dead was put at 138 men, 35 women and 56 children, or approximately 230 overall.[30][33] Some scholars argue that the Natchez spared the African slaves due to a general sense of affinity between the Natchez and the Africans; some enslaved people joined the Natchez against the people who held them against their will, while others took the chance to effect their own freedom.[30] A group of Yazoo people who were accompanying Commandant du Codère remained neutral during the conflict but were inspired by the Natchez revolt. When they returned to Fort St. Pierre, they destroyed the fort, killing the Jesuit priest and 17 French soldiers.[34]

The Natchez lost only about 12 warriors during the attack.[35] Eight warriors died attacking the homestead of the La Loire des Ursins family, where the men had been able to prepare a defense against the intruding Natchez.[30]

Chépart himself was taken captive by the Natchez, who were at first unsure what to do with him, but finally decided that he should be killed by a stinkard—a member of the lowest caste in the tribe's hierarchy.[32] The Natchez kept two Frenchmen alive, a carter named Mayeux who was made to carry all the goods of the French to the Great Village, and a tailor named Le Beau who was employed by the Natchez to refit the colonists' clothing to new owners.[30] They set fire to the fort, the store, and all the homesteads, burning them to the ground.[36] Just as Governor Bienville had done with the executed Indians in 1717 and 1723, the Natchez beheaded the dead Frenchmen and brought the severed heads for the Great Sun to view.[30]

French response

News of the Fort Rosalie attack reached New Orleans in early December, and the colonists there began to panic.[37] The city depended upon grain and other supplies from the Illinois settlement, and shipments up and down the Mississippi River would be threatened by the loss of Fort Rosalie.[38] Governor Périer reacted to the massacre by forbidding the entry of a delegation of Choctaw people into the city, for fear that they were using the pretext of a friendly visit to launch an attack.[39] He then ordered slaves and French troops to march downstream and massacre a small village of Chaouacha people who had played no part in the uprising in Natchez. His superiors in Paris reprimanded the leader for this act, which may have been intended to prevent any alliance between slaves and Native Americans against the French colonists.[13][40] Many Louisiana colonists—Dumont de Montigny in particular—blamed Chépart (who was killed by the Natchez) and Périer for the massacre; Louis XV, the French king, ordered Périer back to France in 1732. Périer's replacement was his predecessor, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, whom the French state thought to be more experienced at dealing with the Native Americans of the region.[41] A year earlier, the Company of the Indies had given up control of the colony to Louis XV because it had been costly and difficult to manage even before the rebellion.[42]

More serious retaliation against the Natchez began late in December and in January 1730, with expeditions led by Jean-Paul Le Sueur and Henri de Louboëy.[43][44] The two commanders besieged the Natchez in forts built near the site of the Grand Village of the Natchez, a mile or so east of Fort Rosalie, which had been rebuilt. They killed about 80 men and captured 18 women, and released some French women who had been captured during the massacre of Fort Rosalie.[35] The French relied on allied support from Tunica and Choctaw warriors. The Choctaw attacked the Natchez without the French, killing 100 and capturing women and children.[45] This ruined the element of surprise for the French as the Natchez had already scattered.[46] At first, the Natchez were well prepared for French retaliatory strikes, having stocked up several cannons as well as the firearms that they had used in the massacre two months earlier.[47][48] The Natchez captured by the Choctaw and Tunica allies of the French were given over to the governor and sold into slavery, and some were publicly tortured to death in New Orleans.[49]

In late February 1730, with Louboëy seeking to catch the Natchez by surprise, the Natchez negotiated a peace treaty and freed French captives, but the French planned an attack on the Natchez fort the following day. The Natchez then brought gifts to Louboëy, but left their fort that night and escaped across the Mississippi River, taking African slaves with them.[50][51] The next day, Louboëy and his men burned down the abandoned Grand Village fort as the Natchez hid in the bayous along the Black River. A subsequent expedition led by Périer in 1731 to dislodge the Natchez captured many of them and their leaders, including Saint Cosme, who was the new Great Sun, and his mother—the Female Sun, Tattooed Arm. The 387 captives, most of whom had belonged to the pro-French faction of the Natchez, were sold into slavery in Saint-Domingue.[52] Many other Natchez escaped again, now taking refuge with the Chickasaw.[53][54] Over the next decade, the few hundred remaining Natchez lived a life on the run, waging a low-intensity guerrilla campaign against the French.[55] French historian Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix wrote in his history, "We were not slow in perceiving that the Natchez could still render themselves formidable, and that the step of sending the Sun and all who had been taken with him to be sold as slaves in Saint-Domingue, had rather exasperated than intimidated the remnant of that nation, in whom hatred and despair had transformed their natural pride and ferocity into a valor of which they were never deemed capable."[56]

The French continued to press for the destruction of the Natchez who now lived among the Chickasaw, traditional allies of the British—this sparked the Chickasaw Wars. The Chickasaw at first agreed to drive out the Natchez from among them, but they did not keep good on the promise.[57] In the Chickasaw Campaign of 1736, the French, under Governor Bienville, attacked the Chickasaw villages of Apeony and Ackia, and then retreated, suffering significant casualties, but inflicting few.[58] In the Chickasaw Campaign of 1739, Bienville summoned more than 1,000 troops to be sent over from France. Bienville's army ascended the Mississippi River to the site of present-day Memphis, Tennessee, and attempted to build a military road westward toward Chickasaw villages. After waiting for months in the winter of 1739–40, the French never mounted an attack and retreated back to New Orleans.[59] After having suffered the attacks against the Chickasaw, the remaining Natchez moved on to live among the Cherokee and Creek people. By that time the Natchez, reduced to scattered refugees, had ceased to exist as a political entity.[46][60]

Historical interpretations

.jpg)

The Natchez revolt figured as an event of monumental significance in French historiography and literature of the 18th and 19th centuries. In France, the massacre and its aftermath was described in numerous historical works and inspired several works of fiction.[61] Eighteenth-century historians generally attributed the Natchez uprising to oppression by Commandant Chépart.[62]

In the French sources, one important discussion has centered on the question of whether the Natchez planned a simultaneous attack on the French with the other major tribes of the region. French colonial governor Étienne Périer, in a report to superiors in France written one week after the revolt, claimed that many of the Indian nations in the lower Mississippi Valley had plotted with the Natchez to attack the French on the same day and that even the Choctaw, who had been close allies of the French, were part of the plot. Périer then cancelled a meeting with the Choctaw planned for the first two days of December in New Orleans, contending that it was to be the occasion for an attack.[63] Périer in this way defended his actions as governor by insinuating that the results of the massacre could have been worse if not for his prompt action.[64][65] However, historians Gordon Sayre and Arnaud Balvay have pointed out that Jean-Baptiste Delaye, a militia commander in the French retaliations following the massacre, wrote in a 1730 unpublished narrative that Périer's claims were groundless, and that the Tioux, Yazoo, and other nations were not complicit and had no foreknowledge of the attack.[61][66][67] Another document in French, of anonymous authorship, asserted that the Natchez revolt was a British plan to destroy a new French tobacco business in Louisiana.[68]

To describe the details of the attack and its background, Dumont de Montigny and Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz, the leading 18th-century historians of Louisiana, drew on information collected from French women taken captive during the massacre. They explained that the Natchez had conspired with other nations but had attacked a few days earlier than the date agreed upon and that they had used a system of bundles of sticks held by each of the conspiring tribes in order to count down the number of days remaining until the strike.[69] The undetected destruction of a couple of the sticks in the Natchez Grand Village derailed the count, although the reason for the lost sticks differed in each historian's account. The other nations called off their participation in the plot because of the Natchez' premature attack, and therefore the very existence of the conspiracy remained conjectural.[70][71][72]

François-René de Chateaubriand depicted the massacre in his 1827 epic Les Natchez,[73] incorporating his earlier best-selling novellas Atala and René into a longer narrative that greatly embellished the history of the French and the Natchez in Louisiana. In Chateaubriand's work, the grand conspiracy behind the massacre implausibly included native tribes from all across North America. Chateaubriand saw the Natchez Massacre as the defining moment in the history of the Louisiana colony,[74] a position consistent with the views of other 18th-century historians, such as Le Page du Pratz and Dumont de Montigny.[75][76]

The 19th-century Louisiana historian Charles Gayarré also embellished the story of a conspiracy behind the Natchez revolt, composing in his book a lengthy speech by the Great Sun in which the leader exhorted his warriors to invite the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Yazoo to join in the attack on the French.[77] In his 2008 book on the Natchez revolt, Arnaud Balvay wrote that more likely than not, the conspiracy claim was false because of incoherence in primary sources.[78]

In contrast to the French tradition, the Natchez and their conflicts with the French have been mostly forgotten in contemporary American historiography. Historian Gordon Sayre attributes this to the fact that both the French and the Natchez were defeated in colonial wars before the birth of the United States.[61][79]

See also

References

- Liebersohn 2001, p. 49.

- Kimball 2005, p. 450.

- Balvay 2013, pp. 140–41.

- Sayre 2005, p. 217.

- Lorenz 1997, passim.

- Albrecht 1946, p. 334.

- Balvay 2013, p. 143.

- Albrecht 1946, p. 335.

- Balvay 2013, p. 147.

- Barnett 2007, pp. 80–95.

- Dumont de Montigny 2012, pp. 227–28.

- Balvay 2013, p. 146.

- Balvay 2013, p. 148.

- Lorenz 2000, pp. 163, 172.

- Cushman 1899, p. 540.

- Barnett 2007, pp. 80–85.

- Le Page du Pratz 1758, pp. 230–31.

- Usner 1998, p. 26.

- Le Page du Pratz 1758, p. 252.

- Barnett 2007, p. 108.

- Dumont de Montigny 2012, pp. 230–31.

- Barnett 2007, pp. 104, 108, 115.

- Usner 1998, p. 27.

- Dumont de Montigny 2012, p. 232.

- Barnett 2007, p. 115.

- Le Page du Pratz 1758, pp. 256–58.

- Le Page du Pratz 1758, p. 258.

- Le Page du Pratz 1758, p. 257.

- Barnett 2007, p. 104.

- Barnett 2007, p. 105.

- Le Page du Pratz 1774, p. 34.

- Dumont de Montigny 2012, p. 233.

- Boler, Jaime (February 2006). "Slave Resistance in Natchez, Mississippi (1719–1861)". Mississippi History Now. Mississippi Historical Society. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- Barnett 2007, p. 106.

- Mooney 1899, p. 512.

- Le Page du Pratz 1758, pp. 260–61.

- Le Page du Pratz 1774, p. 73.

- Sayre 2009, p. 410.

- Dumont de Montigny 2012, pp. 238, 250.

- Rowland, Sanders & Galloway 1984, pp. 45–52.

- Balvay 2008, p. 176.

- Barnett 2007, pp. 125–26.

- Giraud 1991, pp. 410–15.

- Dumont de Montigny & Le Mascrier 1753, pp. 183–91.

- Barnett 2007, p. 114.

- Balvay 2013, p. 149.

- Dumont de Montigny 2012, pp. 240, 242–48.

- Barnett 2007, p. 118.

- Barnett 2007, p. 119.

- Dumont de Montigny 2012, pp. 246–47.

- Delaye 1730, pp. 57–58.

- Barnett 2007, p. 125.

- Dumont de Montigny 2012, p. 247.

- Le Page du Pratz 1758, pp. 291–303.

- Barnett 2007, p. xvii.

- Mooney 1899, p. 514.

- Atkinson 2004, p. 41.

- Atkinson 2004, pp. 55–60.

- Atkinson 2004, pp. 39–73, 247–57.

- Mooney 1899, passim.

- Sayre 2005, p. 204.

- Balvay 2013, p. 151.

- Sayre 2005, pp. 232–34.

- Sayre 2005, p. 245.

- Barnett 2007, pp. 106–07.

- Delaye 1730, p. 62.

- Balvay 2008, pp. 156–57.

- Balvay 2013, pp. 150–51.

- Sayre 2002, pp. 396–97, 400–01, 403, 409.

- Dumont de Montigny & Le Mascrier 1753, pp. 134–38.

- Le Page du Pratz 1758, p. 250.

- Sayre 2005, p. 237.

- Balvay 2008, pp. 15–20.

- Chateaubriand 1827, p. 2.

- Le Page du Pratz 1758, p. 331.

- Dumont de Montigny & Le Mascrier 1753, pp. 145–46, 160, 166–72, 176, 192.

- Gayarré 1854, pp. 396–402.

- Balvay 2008, p. 159.

- Sayre 2002, p. 407.

Bibliography

- Albrecht, Andrew C. (1946). "Indian-French Relations at Natchez". American Anthropologist. New Series. Arlington County, Virginia: American Anthropological Association. 48 (3): 321–354. doi:10.1525/aa.1946.48.3.02a00010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Atkinson, James R. (2004). Splendid Land, Splendid People: The Chickasaw Indians to Removal. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 9780817313395. OCLC 52057896.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Balvay, Arnaud (2008). La Révolte des Natchez (in French). Paris, France: Éditions du Félin. ISBN 9782866456849. OCLC 270986289.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Balvay, Arnaud (2013). "The French and the Natchez: A Failed Encounter". In Robert Englebert; Guillaume Teasdale (eds.). French and Indians in the Heart of North America, 1630–1815. East Lansing, Michigan: Michigan State University Press. OCLC 847023545.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barnett, James F. Jr. (2007). The Natchez Indians: A History to 1735. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781578069880. OCLC 86038006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chateaubriand, François-René de (1827). Les Natchez (in French). Paris, France: Eugène et Victor Penaud Frères. OCLC 3412373.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cushman, Horatio Bardwell (1899). History of the Choctaw, Chickasaw and Natchez Indians. Greenville, Texas: Headlight Printing House. OCLC 1572608.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Delaye, Jean-Baptiste (1730). Relation du massacre des françois aux Natchez et de la guerre contre ces sauvages, 1er juin 1730 (in French). Centre des Archives d'outre-mer, 04DFC 38.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Translation by Gordon Sayre)

- Dumont de Montigny, Jean-François-Benjamin; Le Mascrier, Jean-Baptiste (1753). Mémoires historiques sur la Louisiane (in French). II. Paris, France: Cl. J. B. Bauche. OCLC 55548267.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dumont de Montigny, Jean-François-Benjamin (2012) [1747]. Sayre, Gordon; Zecher, Carla (eds.). The Memoir of Lieutenant Dumont, 1715–1747: A Sojourner in the French Atlantic. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807837221. OCLC 785863931.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gayarré, Charles (1854). History of Louisiana: The French Domination. I. New York, New York: Redfield. OCLC 10994331.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Giraud, Marcel (1991). A History of French Louisiana: Volume V: The Company of the Indies, 1723–1731. V. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807115718. OCLC 493382682.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kimball, Geoffrey (2005). "Natchez". In Janine Scancarelli; Heather Kay Hardy (eds.). Native Languages of the Southeastern United States. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803242357. OCLC 845818920.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Le Page du Pratz, Antoine-Simon (1758). Histoire de la Louisiane (in French). III. Paris, France: De Bure & Delaguette. OCLC 310876492.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Translation by Gordon Sayre)

- Le Page du Pratz, Antoine-Simon (1774) [French version published in 1763]. The History of Louisiana. London, United Kingdom: T. Becket. OCLC 1949294.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Liebersohn, Harry (2001). Aristocratic Encounters: European Travelers and North American Indians. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521003605. OCLC 47917547.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lorenz, Karl G. (1997). "A Re-examination of Natchez Sociopolitical Complexity: A view from the Grand Village and Beyond". Southeastern Archaeology. Southeastern Archaeological Conference. 16 (2): 97–112.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lorenz, Karl G. (2000). "The Natchez of Southwest Mississippi". In Bonnie G. McEwan (ed.). Indians of the Greater Southeast: Historical Archaeology and Ethnohistory. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813017785. OCLC 313827424.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mooney, James (1899). "The End of the Natchez". American Anthropologist. New Series. Arlington County, Virginia: American Anthropological Association. 1 (3): 510–21. doi:10.1525/aa.1899.1.3.02a00050.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rowland, Dunbar; Sanders, A. G.; Galloway, Patricia Kay, eds. (1984). Mississippi Provincial Archives: 1729–1748. IV. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807110683. OCLC 490934898.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sayre, Gordon (2002). "Plotting the Natchez Massacre: Le Page du Pratz, Dumont de Montigny, Chateaubriand". Early American Literature. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. 37 (3): 381–413. doi:10.1353/eal.2002.0030. OCLC 479480590.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sayre, Gordon (2005). The Indian Chief as Tragic Hero. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807829707. OCLC 58788866.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sayre, Gordon (Fall 2009). "Natchez Ethnohistory Revisited: New Manuscript Sources by Le Page du Pratz and Dumont de Montigny". Louisiana History. Lafayette, Louisiana: Louisiana Historical Association. 50 (4): 407–36.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Usner, Daniel H. Jr. (1998). American Indians in the Lower Mississippi Valley. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803245563. OCLC 38976251.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Description of the massacre from Gettysburg College

- "Massacre at Fort Rosalie" – description and list of known survivors from Adams County, Mississippi Genealogical and Historical Research

- "A Failed Enterprise: The French Colonial Period in Mississippi" from the Mississippi Historical Society