Nam tiến

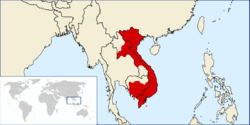

Nam tiến (Vietnamese: [nam tǐən], lit. "southward advance" or "march to the south") refers to the southward expansion of the territory of Vietnam from the 11th century to the mid-19th century. The Vietnamese domain was gradually expanded to the south from its original heartland in the Red River Delta. In a span of some 700 years, Vietnam tripled its territory in size and more-or-less acquired its elongated shape of today.[1]

The direction of expansion to the south could be explained by geographic and demographic factors. With the South China Sea to the east, the Truong Son Mountains to the west, and China to the north, the Vietnamese polity pushed south, following the coastal plains. The 11–14th centuries saw battle gains and losses as the frontier territory changed hands between the Vietnamese and Chams. In the 15–17th centuries following the failed Ming conquest (1407–1420), the resurgent Vietnamese took the upper hand, defeating the less-centralized state of Champa, forcing the cession of more land. By the 17–19th centuries, Vietnamese settlers had penetrated the Mekong Delta. The Nguyen Lords of Hue by diplomacy and by force wrested the southernmost territory from Cambodia, completing the "March to the South".

History

Later Lê Dynasty to the Nguyễn Lords

The native inhabitants of the Central Highlands are the Degar (Montagnard People) peoples. Vietnam conquered and annexed the area during its southward expansion.

Cham provinces were seized by the Vietnamese Nguyen lords.[2] Provinces and districts originally controlled by Cambodia were taken by Vo Vuong.[3][4]

Cambodia was constantly invaded by the Nguyen lords. Around a thousand Vietnamese settlers were slaughtered in 1667 in Cambodia by a combined force of Chinese and Cambodians. Vietnamese settlers started to inhabit the Mekong Delta that was previously inhabited by the Khmer and in response the Vietnamese were subjected to Cambodian retaliation.[5] The Cambodians told Catholic European envoys that the Vietnamese persecution against Catholics justified retaliatory attacks launched against the Vietnamese colonists.[6]

Nguyễn Dynasty

.jpg)

Vietnamese Emperor Minh Mang enacted the final conquest of the Champa Kingdom after the centuries long Cham–Vietnamese wars. The Cham Muslim leader Katip Suma was educated in Kelantan and came back to Champa to declare a Jihad against the Vietnamese after Emperor Minh Mang's annexation of Champa.[7][8][9][10] The Vietnamese coercively fed lizard and pig meat to Cham Muslims and cow meat to Cham Hindus against their will to punish them and assimilate them to Vietnamese culture.[11]

Minh Mang sinicized ethnic minorities such as Cambodians, claimed the legacy of Confucianism and China's Han dynasty for Vietnam, and used the term Han people 漢人 (Hán nhân) to refer to the Vietnamese.[12] Minh Mang declared that "We must hope that their barbarian habits will be subconsciously dissipated, and that they will daily become more infected by Han [Sino-Vietnamese] customs."[13] These policies were directed at the Khmer and hill tribes.[14] The Nguyen lord Nguyen Phuc Chu had referred to Vietnamese as "Han people" in 1712 when differentiating between Vietnamese and Chams.[15] The Nguyen Lords established đồn điền, or state-owned agribusiness, after 1790. Emperor Gia Long (Nguyễn Phúc Ánh), when differentiating between Khmer and Vietnamese, said, "Hán di hữu hạn [ 漢|夷|有限 ]" meaning "the Vietnamese and the barbarians must have clear borders."[16] His successor, Minh Mang, implemented an acculturation integration policy directed at minority non-Vietnamese peoples.[17] Phrases like thanh nhân (清人) or đường nhân (唐人) were used to refer to ethnic Chinese by the Vietnamese while Vietnamese called themselves as Hán dân (漢民) and Hán nhân (漢人) in Vietnam during the 1800s under the rule Nguyễn Dynasty.[18]

Legacy

French colonial rule to the late-twentieth century

During the French colonial era, ethnic strife between Cambodia and Vietnam was somewhat pacified as both were parts of French Indochina. However, inter-group relations deteriorated even further as the Cambodians viewed the Vietnamese as being a privileged group and one that was allowed to migrate into Cambodia. Post-colonial Cambodian regimes, including the governments of Lon Nol and of the Khmer Rouge, all relied on anti-Vietnamese rhetoric to win popular support.[19]

Today

In the twenty-first century, anti-Vietnamese sentiments, due to Vietnam's conquest of previously Cambodian lands which are now the Mekong-Delta part of modern-day Vietnam and hundreds of years of Vietnamese invasions, settling in Cambodia, and military subjugation of Cambodia, persist. This has led to hostilities against ethnic-minority Vietnamese in Cambodia and against Vietnam itself. This is what motivates pro-Chinese sentiment among the Cambodian government and opposition alike on a variety of issues, including in the territorial disputes in the South China Sea. For Cambodia, partnership with Vietnam's traditional enemy, China, is highly beneficial. Cambodian politician Sam Rainsy defended this position thus, "...when it comes to ensuring the survival of Cambodia as an independent nation, there is a saying as old as the world: the enemy of my enemy is my friend."[19]

See also

- History of the Cham–Vietnamese wars

- Champa

- Chey Chettha II

- Khmer Empire

- Cambodian–Vietnamese War of the 1970s and 1980s

References

- Nguyen The Anh, Le Nam tien dans les textes Vietnamiens, in P.B. Lafont; Les frontieres du Vietnam; Edition l’Harmattan, Paris 1989

- Elijah Coleman Bridgman; Samuel Wells Willaims (1847). The Chinese Repository. proprietors. pp. 584–.

- George Coedes (May 15, 2015). The Making of South East Asia (RLE Modern East and South East Asia). Taylor & Francis. pp. 175–. ISBN 978-1-317-45094-8.

- G. Coedes; George Cœdès (1966). The Making of South East Asia. University of California Press. pp. 213–. ISBN 978-0-520-05061-7.

- Ben Kiernan (2008). Blood and Soil: Modern Genocide 1500-2000. Melbourne Univ. Publishing. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-0-522-85477-0.

- Ben Kiernan (2008). Blood and Soil: Modern Genocide 1500-2000. Melbourne Univ. Publishing. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-522-85477-0.

- Jean-François Hubert (May 8, 2012). The Art of Champa. Parkstone International. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-1-78042-964-9.

- "The Raja Praong Ritual: A Memory of the Sea in Cham- Malay Relations". Cham Unesco. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- (Extracted from Truong Van Mon, “The Raja Praong Ritual: a Memory of the sea in Cham- Malay Relations”, in Memory And Knowledge Of The Sea In South Asia, Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences, University of Malaya, Monograph Series 3, pp, 97-111. International Seminar on Maritime Culture and Geopolitics & Workshop on Bajau Laut Music and Dance”, Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences and the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya, 23-24/2008)

- Dharma, Po. "The Uprisings of Katip Sumat and Ja Thak Wa (1833-1835)". Cham Today. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- Norman G. Owen (2005). The Emergence Of Modern Southeast Asia: A New History. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 115–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2890-5.

- A. Dirk Moses (January 1, 2008). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. Berghahn Books. pp. 209–. ISBN 978-1-84545-452-4. Archived from the original on 2008.

- Randall Peerenboom; Carole J. Petersen; Albert H.Y. Chen (September 27, 2006). Human Rights in Asia: A Comparative Legal Study of Twelve Asian Jurisdictions, France and the USA. Routledge. pp. 474–. ISBN 978-1-134-23881-1.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20040617071243/http://kyotoreview.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/issue/issue4/article_353.html

- Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 136–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- Choi Byung Wook (2004). Southern Vietnam Under the Reign of Minh Mạng (1820-1841): Central Policies and Local Response. SEAP Publications. pp. 137–. ISBN 978-0-87727-138-3.

- Greer, Tanner (January 5, 2017). "Cambodia Wants China as Its Neighborhood Bully". Foreign Policy.