Nadvirna

Nadvírna, also referred to as Nadwirna or Nadvorna (Ukrainian: Надві́рна, Polish: Nadwórna, Yiddish: נאַדוואָרנאַ, Nadvorna) is a city located in Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast in western Ukraine. It is the administrative centre of Nadvirna Raion. Population: 22,281 (2016 est.)[1].

Nadvirna Надвiрна Nadwórna | |

|---|---|

Pniv Castle | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

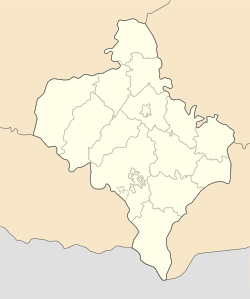

Nadvirna Location of Nadvirna within Ukraine  Nadvirna Nadvirna (Ukraine) | |

| Coordinates: 48°38′N 24°35′E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | |

| Raion | Nadvirna Raion |

| Area | |

| • Total | 25.53 km2 (9.86 sq mi) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 22,281 |

| • Density | 870/km2 (2,300/sq mi) |

From the mid-14th century until 1772 (see Partitions of Poland) Nadvirna, known in Polish as Nadwórna, was part of the Kingdom of Poland. In 1772, it was annexed by the Habsburg Empire, and remained in the province of Galicia until late 1918. In the inter-war years, the borders changed and the town became part of the Second Polish Republic. Following the 1939 Invasion of Poland, it was annexed into the Ukrainian SSR (see also Molotov-Ribbentrop pact). Nadvirna was occupied by the Germans in 1941 during World War II. After the war it was once again absorbed into the Ukrainian SSR. Since its independence in 1991, the city has been part of Ukraine.

The town is located in a slightly hilly, verdant area twenty miles (32 km) northeast of the Carpathian mountains. Major exports and raw materials from the town include salt, oil and petroleum products, and timber. The town was popular at the start of the 20th century as a summertime resort, with restaurants and hotels.

History

Evidence of the early settlement in the region around Nadvirna dates back to 2000 BC. Numerous finds of Bronze Age artifacts attest to a vibrant culture. The town was built around the Pniv castle. The Pniv (Polish: Pniów) Castle was probably built in the second half of the 16th century by the Stolnik of Halych (Halicz), Paweł Kuropatwa, as a residence of his family. The castle was successfully defended in 1621, in 1648, and in 1676, during the Polish–Ottoman War (1672–76). Abandoned in the 18th century, it turned into a ruin.

The town itself is first mentioned in chronicles dating back to 1589, in an act describing an attack on the inhabitants by Tatars. In the second half of the 16th century the town received self-governing status. In the period of Halych, the town was situated on a major trading route and a taxation office was located there. The shield of the Kuropat family has been adopted for use by the town of Nadvirna. After an attack by the Tartars, the Kuropat family built a more inaccessible fortress in 1589. In 1621, the Opryshky under the leadership of Hrynia Kardash had their base of operations close by. In 1648 the inhabitants took part in the Cossack insurrection under Bohdan Khmelnytsky. Soldiers from Nadvirna joined the forces of Bohdan Khmelnytsky in his drive to Lviv. In the 17th century the town became an important centre for the building professions and also an important centre for trade. Trade from Hungary to central Ukraine traveled through Nadvirna.

In 1805, a court was set up in the town. In the 19th century the trades began to be replaced by factory manufacturing. One of the largest factories in Galicia for the construction of farm machinery was built in 1843. These machines were demonstrated at the second world exhibition held in Vienna in 1844. In 1870 a match factory was built in the town. In 1886 deposits of oil were discovered locally. In 1893 a railway line was built to Stanislaviv. The first train traveled the line on October 21, 1894. In the late 18th century, Count Ignacy Cetner founded here a tobacco field, excavated local salt deposits, and invited German settlers. After World War I and the Polish–Ukrainian War, Nadwórna returned to Poland, where it remained until the 1939 Invasion of Poland.

During World War I, the 2nd Brigade of the Polish Legions operated in the area of Nadvirna. In the winter of 1914/1915, the brigade faced here the Imperial Russian Army, which planned to cross the Carpathian Mountains, and enter Hungary. In 1929, in a nearby village of Starunia, almost complete Woolly rhinoceros was found, preserved in ozokerite. This unique trove, one of its kind, is now kept at Kraków’s Nature Museum. Altogether, in 1907 – 1932, four rhinoceroses and one mammoth were found in the area of Nadvirna. In the interbellum period, the mammoth and one of the rhinoceroses were kept at the Dzieduszycki Nature Museum in Lviv (then Lwow). After World War II, they remained in the city, and are still kept in the now-Ukrainian museum.

In June 1941, some 80 inmates of the local NKVD prison were murdered along the Bystrytsya river, their bodies were unearthed and properly buried in July 1941. Among the victims were women and children (see NKVD prisoner massacres). During the war, almost all of the 4500 Jewish residents of Nadvirna, men, women, and children, were murdered by Germans and by Ukrainian townspeople and police.[2] In 1945, Polish residents of the town were forced to leave the area and the handful of survivors of the Jewish population did not return. Most of the Poles later settled in Prudnik and Opole.

Nadvirna has a Greek-Catholic church and a Roman Catholic Cathedral in the name of the Trinity built in 1599. A Roman Catholic parish was formed in 1609.

In the 16th and 17th centuries most of the population of 2233 was illiterate. In the 18th century a school was built to serve 100 students using a German and a Jewish curriculum .

Jewish population

Nadvirna once had a large Jewish population, whose recorded history in the city dates from at least 1765. The city is still known for its Hasidic dynasty and rabbinical families, many of whom now live in Israel.

In 1880, a census showed that there were 6,552 people living in Nadvirna, of whom 4,182 (64%) were Jewish. But by 1890, there were 7,227 inhabitants, 3,618 (50%) of them Jewish, and by 1921, there were 6,062 inhabitants, 2,042 (34%) of them Jewish. By the end of 1942 all but a very few of the Nadvirna Jews had been murdered in the Holocaust, some in ghettos created in the city, but many killed in the Belzec concentration camp.

There is a memorial to the victims of the Holocaust from Nadvirna in the Baron Hirsch Cemetery Staten Island, New York where the Nadworna landsmanshaft has a section. A photo can be found here.[3]

The emblematic blue box of the Jewish National Fund was invented by a bank clerk from Nadvirna named Haim Kleinman. Kleinman visited Israel in the 1930s and planned to make aliyah, but was murdered in the Holocaust.[4]

On August 12th, 2018, the Nadworna Shtetl Research Group dedicated a monument to the victims of the Holocaust from Nadvirna in the Nadvirna Jewish Cemetery.

.jpg)

Jewish genealogical records

As of late 2006, the following vital records of the town's former Jewish community were known to have survived, and were available for genealogical research:

- Birth records: early 1850 – late 1865 – stored at the Central State Historical Archives of Ukraine, in Lviv, Ukraine

- Birth records: 1866–1897; 1903 – stored at the Central Archives of Historical Records (a.k.a. AGAD), in Warsaw, Poland

- Birth records: 1898–1938 – stored at Urzad Stanu Cywilnego, Warszawie Archiwum (a.k.a. the Warsaw USC Office), in Warsaw, Poland

- Marriage records: 1890–1939; 1942 – stored at Urzad Stanu Cywilnego, Warszawie Archiwum (a.k.a. the Warsaw USC Office), in Warsaw, Poland

- Death records: 1868–1892 – stored at the Central Archives of Historical Records (a.k.a. AGAD), in Warsaw, Poland

- Death records: 1893–1940; 1942 – stored at Urzad Stanu Cywilnego, Warszawie Archiwum (a.k.a. the Warsaw USC Office), in Warsaw, Poland

- Kehilla (Jewish community) records: 1924–1939 – stored at the State Archive of Ivano-Frankovsk Oblast, in Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine

- Kehilla (Jewish community) records: 1933–1935 (Registry of local Zionist organization) – stored at the Central State Historical Archives of Ukraine, in Lviv, Ukraine

- Holocaust records: 1941–1944 – stored at the State Archive of Ivano-Frankovsk Oblast, in Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine

- Property records: 1785–1788; 1819–1820; 1847–1879 – stored at the Central State Historical Archives of Ukraine, in Lviv, Ukraine

- Police and KGB records: 1920–1932 – stored at the State Archive of Ivano-Frankovsk Oblast, in Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine

This is only a partial list of available records, and it only references records from the actual town of Nadvirna proper. There are also records available from the "Nadworna Poviat", which is the larger administrative district that included several smaller local villages.

Note that records less than 100 years old stored in Poland — which in this case means either AGAD or the Warsaw USC office — are not open to the public due to strict Polish privacy laws. This does not affect records stored in Ukraine.

Some of these vital records, particularly the ones stored at AGAD in Warsaw, have been microfilmed by the Mormons (LDS Church) and the microfilms are available to research at their Family History Centers, free of charge.

People from Nadvirna

- in 1929, Volodymyr Luciv (Ukrainian: Володимир Луців) was born. He grew up to be a worldwide famous Bandurist and tenor. He now resides in London.

- Zygmunt Antkowiak – Polish historian and journalist

- Roman Korban – Polish athlete, olympian

- Jozef Oktawiec – Socialist politician, a deputy to the Polish Sejm in 1927.

- Jadwiga Woloszynska – Polish scientist, professor of biology.

- Mariyka Pidhiryanka – Ukrainian poet

- Manfred Joshua Sakel, Polish neurophysiologist, psychiatrist

- Abraham David ben Asher Anshel Buchach, rabbi

- Mordechai of Nadvorna, rabbi

- Olena Saiko – Sambo and judo international competitor[5]

International relations

External links

- Detailed topographical map (in Russian) of Nadvirna and its surrounding towns

- Shtetl Nadworna – includes names of many immigrants from Nadvirna to the United States through benevolent societies and cemetery records

- Selected translations from the Nadvirna Yizkor (memorial) book describing everyday life

- History of the city, including a detailed timeline of the Holocaust against its Jews

- Jewish history and Photographs of Jewish sites in Nadvirna in Jewish History in Galicia and Bukovina

- Nadworna Shtetl Research Group

- Nadworna Jewish Cemetery fully documented at Jewish Galicia and Bukovina ORG

References

- "Чисельність наявного населення України (Actual population of Ukraine)" (PDF) (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Megargee, Geoffrey (2012). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. p. Volume II, 810-811. ISBN 978-0-253-35599-7.

- http://www.museumoffamilyhistory.com/hm-nadvirna-bh.htm

- Moshe Kol-Kalman, The Blue Box, The Israel Philatelist, June 2009, Vol LX, No. 3, p. 116-7.

- http://www.baku2015.com/athletes/athlete/SAYKO-Olena-1006672/index.html?intcmp=sport-hp