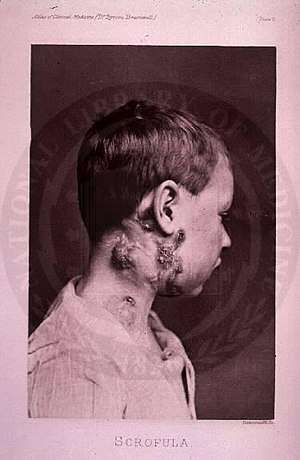

Mycobacterial cervical lymphadenitis

The disease mycobacterial cervical lymphadenitis, also known as scrofula and historically as king's evil, involves a lymphadenitis of the cervical lymph nodes associated with tuberculosis as well as nontuberculous (atypical) mycobacteria.

| Mycobacterial cervical lymphadenitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Scrofula, scrophula, struma, the King's evil |

| |

| Scrofula of the neck | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Look up scrofula in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Disease

Scrofula is the term used for lymphadenopathy of the neck, usually as a result of an infection in the lymph nodes, known as lymphadenitis. It can be caused by tuberculous or nontuberculous mycobacteria. About 95% of the scrofula cases in adults are caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, most often in immunocompromised patients (about 50% of cervical tuberculous lymphadenopathy). In immunocompetent children, scrofula is often caused by atypical mycobacteria (Mycobacterium scrofulaceum) and other nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). Unlike the adult cases, only 8% of cases in children are tuberculous.

With the stark decrease of tuberculosis in the second half of the 20th century, scrofula became a less common disease in adults, but remained common in children. With the appearance of AIDS, however, it has shown a resurgence, and presently affects about 5% of severely immunocompromised patients.

Signs and symptoms

The most usual signs and symptoms are the appearance of a chronic, painless mass in the neck, which is persistent and usually grows with time. The mass is referred to as a "cold abscess", because there is no accompanying local color or warmth and the overlying skin acquires a violaceous (bluish-purple) color. NTM infections do not show other notable constitutional symptoms, but scrofula caused by tuberculosis is usually accompanied by other symptoms of the disease, such as fever, chills, malaise and weight loss in about 43% of the patients. As the lesion progresses, skin becomes adhered to the mass and may rupture, forming a sinus and an open wound.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually performed by needle aspiration biopsy or excisional biopsy of the mass and the histological demonstration of stainable acid-fast bacteria in the case of infection by M. tuberculosis (Ziehl-Neelsen stain), or the culture of NTM using specific growth and staining techniques.

Pathology

The classical histologic pattern of scrofula features caseating granulomas with central acellular necrosis (caseous necrosis) surrounded by granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells. Although tuberculous and nontuberculous lymphadenitis are morphologically identical, the pattern is somewhat distinct from other causes of bacterial lymphadenitis.[1]

Treatment

Treatments are highly dependent on the kind of infection. Surgical excision of the scrofula does not work well for M. tuberculosis infections, and has a high rate of recurrence and formation of fistulae. Furthermore, surgery may spread the disease to other organs. The best approach is to use conventional treatment of tuberculosis with antibiotics. The cocktail-drug treatment of tuberculosis (and inactive meningitis) includes rifampicin along with pyrazinamide, isoniazid, ethambutol, and streptomycin ("PIERS"). Scrofula caused by NTM, however, responds well to surgery, but is usually resistant to antibiotics. The affected nodes can be removed either by repeated aspiration, curettage or total excision (with the risk in the latter procedure, however, often causing unsightly scarring, damage to the facial nerve, or both).

Prognosis

With adequate treatment, clinical remission is practically 100%. In NTM infections, with adequate surgical treatment, clinical remission is greater than 95%. It is recommended that persons in close contact with the diseased person, such as family members, be tested for tuberculosis.

History

The word comes from the medieval Latin scrofula, diminutive of scrofa, meaning brood sow.

In the Middle Ages it was believed that royal touch, the touch of the sovereign of England or France, could cure diseases owing to the divine right of sovereigns. Henry VI of England is alleged to have cured a girl with it. Scrofula was therefore also known as the King's evil. From 1633, the Book of Common Prayer of the Anglican Church contained a ceremony for this, and it was traditional for the monarch (king or queen) to present to the touched person a coin—usually an angel, a gold coin the value of which varied from about 6 shillings to about 10 shillings. In England this practice continued until the early 18th century, and was continued by the Jacobite pretenders until the extinction of the House of Stuart with the death of the pretender Henry IX. King Henry IV of France is reported as often touching and healing as many as 1,500 individuals at a time. Queen Anne touched the infant Samuel Johnson in 1712,[2] but King George I put an end to the practice as being "too Catholic". The kings of France continued the custom until Louis XV stopped it in the 18th century, though it was briefly revived by Charles X in 1825.

Physicians, healers, and patent medicine sellers offered a wide range of cures for scrofula or The King's Evil. Since ancient times, mercury, referred to as cinnabar, quicksilver or calomel, was administered as an ointment or pill or inhaled as a vapor to treat skin diseases such as scrofula. Mercury taken internally induced vomiting and sweating, reactions believed to cleanse the body and balance the humors, thus curing the disease. For example, in 1830, The New-York Medical and Physical Journal recommended mercury as the best cure. Alternative treatments were also recommended. Many rejected the harsh side effects of mercury, claiming their cures were made of "natural" or "vegetable" ingredients. For example, patent medications labeled as sarsaparilla were recommended for scrofula.[3]

Examples of treatments recommended between the 17th and 19th century include the following:

- Herbalist Nicholas Culpepper (1616–1654), is claimed to have treated his daughter for scrofula with lesser celandine, and cured her within a week.[4]

- In the 18th century, Elizabeth Pearson, an Irish herbalist, proposed a treatment for scrofula involving herbs and a poultice and extract of vegetable, and in 1815, Sir Gerard Noel presented a petition to the House of Commons advocating her treatment.[5]

- In 1768 the Englishman John Morley produced a handbook entitled Essay on the Nature and Cure of Scrophulous Disorders, Commonly Called the King's Evil. The book starts by listing the typical symptoms and indications of how far the disease had progressed. It then goes into detail with a number of case studies, describing the specific case of the patient, the various treatments used and their effectiveness. The forty-second edition was printed in 1824.

- Richard Carter, a frontier herb doctor in Kentucky, recommended several treatments for the King's Evil, or scrofula, in his 1815 home medical guide Valuable Vegetable Medical Prescriptions for the cure of all Nervous and Putrid Disorders.

- In the 19th century in the United States, the patent medicine Swaim's Panacea was advertised to cure scrofula.[6] Swaim's Panacea contained mercury.

In 1924, French historian Marc Bloch wrote a book[7] on the history of the royal touch: The Royal Touch: Sacred Monarchy and Scrofula in England and France (original in French).

See also

- Scrofuloderma

- Tuberculosis diagnosis

- Tuberculosis treatment

- Touch pieces

References

- Rosado FG, Stratton CW, Mosse CA Clinicopathologic correlation of epidemiologic and histopathologic features of pediatric bacterial lymphadenitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011 Nov; 135(11):1490–93. http://www.archivesofpathology.org/doi/pdf/10.5858/arpa.2010-0581-OA

- Henry Hitchings (2005). Dr Johnson's Dictionary: The Extraordinary Story of the Book that Defined the World. John Murray. p. 11.

- Resor, Cynthia (March 18, 2020). "What is scrofula? Can it be cured?".

- Reader's Digest Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain. Reader's Digest. 1981. p. 26. ISBN 9780276002175.

- "Petition of Mrs. Pearson Respecting Her Discovery For the Cure of Scrofula, or King's Evil". Hansard. 31: 1086–87. 3 July 1815.

- Young, James Harvey. The Toadstool Millionaires, ch. 5 (1961)

- Bloch, M. (Anderson, J. E., trans), The Royal Touch: Sacred Monarchy and Scrofula in England and France (Les Rois Thaumaturges), Routledge & Kegan Paul, (London), 1973.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Werrett, Simon. "Healing the Nation’s Wounds: Royal Ritual and Experimental Philosophy in Restoration England." History of Science 38 (2000): 377-99.

- Scrofula MedPix(r) Images