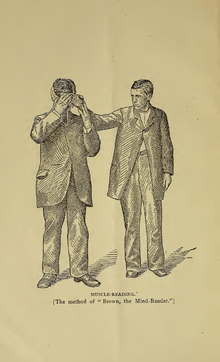

Muscle reading

Muscle reading, also known as "Hellstromism", "Cumberlandism" or "contact mind reading", is a technique used by mentalists to determine the thoughts or knowledge of a subject, the effect of which tends to be perceived as a form of mind reading. The performer can determine many things about the mental state of a subject by observing subtle, involuntary responses to speech or any other stimuli.[1][2] It is closely related to the ideomotor effect, whereby subtle movements made without conscious awareness reflect a physical movement, action or direction which the subject is thinking about. The term "muscle reading" was coined in the 1870s by American neurologist George M. Beard to describe the actions of mentalist J. Randall Brown, an early proponent of the art.[3][4]

History

Muscle reading is also known by the names of those who have used it in popular performances. The success of one early performer, Stuart Cumberland, led to the technique's alternate name of Cumberlandism. The fame of the mentalist Axel Hellstrom led to it widely being called Hellstromism. Performers such as J. Randall Brown, Erik Jan Hanussen, Franz Polgar, and Kreskin have also used muscle reading successfully in their acts.

In 1924, magician Carl Hertz noted that "mind-reading is nothing but muscle-reading. In all the cases where the mind-reader is supposed to lead a person to a hidden object, the spectator is guided entirely by an involuntary movement of the subject's muscles."[5] The mentalist Washington Irving Bishop could drive a car blindfolded by muscle reading techniques.[6]

Kreskin, one of the most accomplished performers of muscle reading in modern times, can tell a driver where to go in a car while a subject holds his wrist (or vice versa). In one of his books he relates the technique to the children's game within which a hidden object is located by feedback of "hot" or "cold".

June Downey had studied the practice of muscle reading from a psychological perspective.[7] She has been described as an expert on the subject of muscle reading.[8]

Technique

The technique relies on the assertion that the subject will subconsciously reveal their thoughts through very slight involuntary physical reactions, also known as ideomotor responses. The performer can determine what the subject is thinking by recognising and interpreting those responses. Muscle reading may be billed by some entertainers as a psychic phenomenon, where the audience will be told that by creating physical contact with the subject, a better psychic connection can be formed. In fact, the contact allows the performer to read more subtle reactions in the subject's motor functions that may not be apparent without contact, such as muscle control and heart rate.

Because muscle reading relies so heavily on the subject's subconscious reactions to their environment and situation, this technique is used commonly when performing stunts dealing with locating objects in an auditorium or on stage, and as such, it can be done 'clean' by the magician skilled in reading body language.

Performers often instruct the subject to imagine voicing instructions, which presumably amplifies the reactions of the subject, thus promoting the idea that the trick involves genuine thought transference or mind-reading. However the subject who is "thinking directions" has a physical, kinaesthetic reaction that guides the performer so that he or she can, for example, locate a specific place on a wall on which to place a pin, without prior knowledge of where the pin should go.

Knowledge of muscle reading is a technique that is also reportedly used by poker players to hide their reactions to the game, as well as to read the other players for potential bluffs and/or better hands.

See also

- Billet reading

- Cold reading

- Ideomotor effect

References

- Christopher, Milbourne. (1996). The Illustrated History of Magic. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 389

- Gardner Martin. (2012 edition, originally published in 1957). Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-20394-8 "The unwitting translation of thoughts into muscular action is one of the most firmly established facts of psychology. In individuals particularly prone to it, it is responsible for such "occult" phenomena as the movement of a Ouija board, table tipping, and automatic writing. It is the basis of a type of mind reading known in the magic profession as "muscle reading." Someone hides a pin in a room, and the performer finds it quickly by having a spectator take hold of his hand. The spectator thinks he is being led by the magician, but actually the performer permits the spectator to lead him by unconscious muscular tensions. Many famous muscle readers are able to dispense with bodily contact altogether, finding the hidden object merely by observing the reactions of spectators in the room."

- Jay, Ricky (1986). Learned Pigs and Fireproof Women. New York City: Villard Books. p. 175.

- During, Simon. (2004). Modern Enchantments: The Cultural Power of Secular Magic. Harvard University Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0674013711

- Hertz, Carl. (1924). A Modern Mystery Merchant. Hutchinson & Company. p. 277

- Neher, Andrew. (2011). Paranormal and Transcendental Experience: A Psychological Examination. Dover Publications. p. 33. ISBN 0-486-26167-0 "Washington Irving Bishop could drive blindfolded through city streets, guided by the involuntary muscle reactions of a passenger who placed his hand on Bishop. In addition, Bishop could drive to a location anywhere in the city where his passenger had hidden an object and, still through reading his guide's muscle reactions, would locate the object in its hiding place."

- Roeckelein, Jon E. (2004). Imagery in Psychology: A Reference Guide. Praeger. p. 238. ISBN 0-313-32197-3

- "June Etta Downey (1875-1932)". Society for the Psychology of Women.

Further reading

- George M. Beard. (1882). The Study of Trance, Muscle-Reading and Allied Phenomena in Europe and America. New York.

- H. J. Burlingame. (1891). Mind-Readers and Their Tricks. In Leaves from Conjurers' Scrap books: Or, Modern Magicians and Their Works. Chicago: Donohue, Henneberry & Co. pp. 108-127

- June Downey. (1908). Automatic Phenomena of Muscle-Reading. The Journal of Philosophy 5: 650-658.

- June Downey. (1909). Muscle-Reading: A Method of Investigating Involuntary Movements and Mental Types. Psychological Review 16: 257-301.

External links

- http://www.randi.org/encyclopedia/muscle%20reading.html - James Randi on the subject

- http://dict.die.net/muscle%20reading/ - dictionary definition

- Marom mor mentalist