Billet reading

Billet reading, or the envelope trick, is a mentalist effect in which a performer pretends to use clairvoyance to read messages on folded papers or inside sealed envelopes. It is a widely performed "standard" of the mentalist craft since the middle of the 19th century. Billet is the French term for note or letter, referring to the rectangular shape of the paper.

.png)

Effect

The mentalist provides paper, pencils and envelopes to the audience, who are asked to write statements on the paper and then seal them in the envelopes. The envelopes are then collected and handed to the mentalist. The mentalist takes the first envelope and magically examines it, typically by holding it to their forehead. After concentrating, they announce what is written on the paper. The envelope is then opened to check that they have read it correctly. The mentalist then selects the next envelope and proceeds to mind-read the contents of the rest, one by one.

History

Billet reading has been a popular trick for mentalists and mediums and spiritualists. It was one of the main acts that brought fame to Charles H. Foster, an American medium who popularized a version using folded slips some time in the 1850s or 60s. In the 1870s he was joined for a time by Bert Reese, who further popularized it. Magician Theodore Annemann talks about several of Reese's variations on the theme in articles in his mentalist's journal The Jinx which were republished after Annemann's death in the book Practical Mental Magic.[1] Reese's work became well known, and was the subject of several explanatory full-page articles in The New York Times.[2]

In his book The Physical Phenomena of Spiritualism, Hereward Carrington revealed the tricks of billet reading (with diagrams) that fraudulent mediums would use.[3] The psychical researcher Eric Dingwall observed Reese in New York and claimed to have discovered his cheating methods; according to Dingwall the exploits of Reese were "not worth any serious scientific consideration" and that Reese came into contact with the sealed notes.[4] Martin Gardner wrote that Reese was an expert mentalist no different from stage magicians of the period such as Joseph Dunninger but managed to fool a number of people into believing he was a genuine psychic.[5] Another magician to expose the methods of billet readers was Joseph Rinn.[6]

Many magicians take delight fooling billet readers in any number of ways. When used as a spiritualist act, the simplest method is to write questions to people who are not yet dead or are just made up, and then watch as the spiritualist pretends to contact the fake name.[7] Another method is to write a statement that is so ribald, funny or startling that it trips up the performer when they read it. Exposing billet readers has a long history.

Method

One-ahead

Most billet reading is an example of a generalized class of tricks known as "one ahead" reading. It is accomplished by having the performer know one of the statements beforehand, typically through a plant, or through sleight of hand by opening one of them before starting the act.[8][9]

To start the act, the mentalist selects the topmost envelope on the stack and pretends to mind-read the contents, typically by holding it to their forehead. Instead of announcing anything related to that envelope, they instead read aloud the memorized statement. The plant in the audience then cries out some variation of "that's mine!" Another variation is to claim to be unable to read the first card due to some problem, perhaps that the audience member's mind is closed or too powerful. In either event, the mentalist then opens the envelope to "make sure they got it right" or perhaps to "see what is so confusing" and is then able to read what a real audience member wrote on their billet.[8][9]

The trick proceeds to the next envelope. The mentalist pretends to mind read it, but reads aloud the statement from the envelope previously opened. This time a real audience member is impressed and agrees they got it right. The mentalist then reads the contents of the second envelope and repeats this sequence. The trick then continues until the envelopes are exhausted, the last one being empty or the envelope of the plant.[8] Throughout, the mentalist is "one ahead" in the envelope stack, pretending to be reading one while actually reading the next one.

To disguise the reason for opening the envelope, the typical variation used by mentalists has the audience members write questions on their cards, which the magician will answer. The magician then starts by making a statement like "I feel beautiful!", expresses some confusion about why he would say that, and then opens the envelope to read the question, "will the weather be nice tomorrow?" (while actually reading the next card, "what is my shoe size?"). As the questions may be impossible to guess, like a random person's shoe size, comedy or misdirection is often worked into the routine. For instance, "a size larger than last year" makes a reasonable answer to shoe size no matter who asks the question. Mediums may use the question and answer format as well, except that the questions are to be asked of the deceased, or perhaps are simply names of people to be contacted in the spirit world.[8]

Other methods

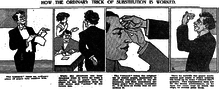

There are numerous variations on the theme of reading sealed notes which use sleight of hand to achieve the basic effect. Many of these involve quick palming of the billet, substitutions with pre-made billets, and other similar tricks. Annemann describes several such methods in depth, and many hundreds can be found in other works or on the internet.[1]

Parodies

Johnny Carson's "Carnac the Magnificent" sketches parodied the billet reading trick by having Carnac announce the (seemingly normal) answer to an unseen question, then open the envelope and read the question, which revealed the answer to be a pun. No attempt at magic is even suggested; Carson simply used the trappings of the well-known trick as stagecraft for his jokes. The bit was borrowed from similar routines performed by Steve Allen ("The Answer Man") and Ernie Kovacs ("Mr. Question Man").

References

Citations

- Theodore Annemann,"Practical Mental Magic" Archived November 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Dover, 1983, pp. 7-11.

- Edward Marschall, "Seeking the Explanation of Reese's "Mind Reading'" Archived February 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 20 November 1910.

- Hereward Carrington. (1907).The Physical Phenomena of Spiritualism Archived March 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Herbert B. Turner & Co. pp. 276-290.

- Eric Dingwall. (1927). How to Go to a Medium. K. Paul, Trench, Trübner. pp. 31-32. Also see Eric Dingwall. (1968). Abnormal Hypnotic Phenomena: France. Barnes & Noble. p. 272

- Martin Gardner. (1957). Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science. Dover Publications. p. 311. ISBN 978-0486203942

- Martin Gardner. (2001). Did Adam and Eve Have Navels?: Debunking Pseudoscience. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 217. ISBN 978-0393322385

- Joe Nickell, "The Mystery Chronicles: More Real-Life X-Files" Archived February 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, University Press of Kentucky, 2010, p. 40.

- Irwin & Watt 2007, p. 43.

- Abbott 1907, pp. 263-265.

Bibliography

- Irwin, Harvey; Watt, Caroline (2007). An Introduction to Parapsychology (5th ed.). McFarland.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Abbott, David (1907). Behind the Scenes with the Mediums.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Ho, Oliver. How to Read Minds & Other Magic Tricks. ISBN 0-8069-7645-4

- Irwin, Harvey J. Introduction to Parapsychology. ISBN 0-8069-7645-4

- Anneman, Theodore. Practical Mental Magic. ISBN 0-486-24426-1