Motya

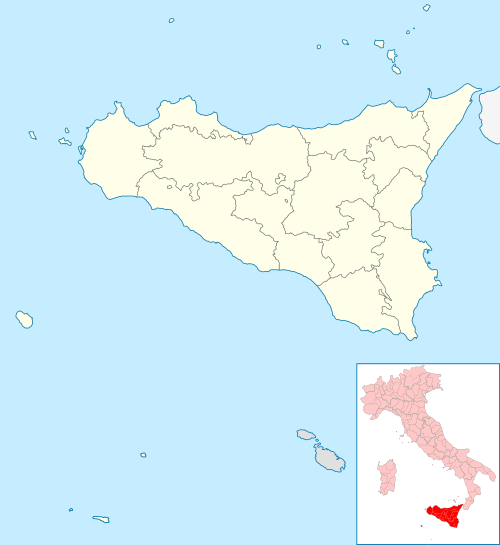

Motya was an ancient and powerful city on San Pantaleo Island off the west coast of Sicily, in the Stagnone Lagoon between Drepanum (modern Trapani) and Lilybaeum (modern Marsala). It is within the present-day commune of Marsala, Italy.

Motya | |

Shown within Sicily | |

| Location | Marsala, Sicily, Italy |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°52′06″N 12°28′07″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

.png)

Many of the city's impressive ancient monuments have been excavated and can be admired today.[1]

Motya has become known recently for the[2] marble statue of the Motya Charioteer,[3] found in 1979 and on display at the local Giuseppe Whitaker museum.[4]

Names

The Carthaginian settlement was written in their abjad as HMṬWʾ (Punic: 𐤄𐤌𐤈𐤅𐤀)[5] or MṬWʾ (Punic: 𐤌𐤈𐤅𐤀, possibly Motye).[6] The name seems to derive from the Phoenician triliteral root MṬR, which would give it the meaning of "a wool-spinning center".

Motya is the latinization of the island's Greek name, variously written Motýa (Μοτύα) or Motýē (Μοτύη). The Greeks claimed the place was named for a woman named Motya whom they connected with the myths around Hercules.[7] The town's Italian name appears as both Mozia and Mothia; its Sicilian name is Mozzia.

The island first received the name San Pantaleo in the 11th century from Basilian monks.

Geography

The island is nearly 850 m (2,790 ft) long and 750 m (2,460 ft) wide, and about 1 km (0.62 mi) (six stadia) from the mainland of Sicily. It was joined to the mainland in ancient times by a causeway, over which chariots with large wheels could reach the town.[8]

History

The foundation of the city probably dates from the eighth century BC, about a century after the foundation of Carthage in Tunisia. It was originally a colony of the Phoenicians, who were fond of choosing similar sites, and probably in the first instance merely a commercial station or emporium, but gradually rose to be a flourishing and important town. The Phoenicians transformed the inhospitable island into one of the most affluent cities of its time, naturally defended by the lagoon as well as high defensive walls. Ancient windmills and salt pans were used for evaporation, salt grinding and refinement, and to maintain the condition of the lagoon and island itself. Recently the mills and salt pans (called the Ettore Infersa) have been restored by the owners and opened to the public.

In common with the other Phoenician settlements in Sicily, it passed under the government or dependency of Carthage, whence Diodorus calls it a Carthaginian colony; but it is probable that this is not strictly correct.[9]

As the Greek colonies in Sicily increased in numbers and importance the Phoenicians gradually abandoned their settlements in the immediate neighbourhood of the newcomers, and concentrated themselves in the three principal colonies of Soluntum, Panormus (modern Palermo), and Motya.[10] The last of these, from its proximity to Carthage and its opportune situation for communication with North Africa, as well as the natural strength of its position, became one of the chief strongholds of the Carthaginians, as well as one of the most important of their commercial cities in the island.[11] It appears to have held, in both these respects, the same position which was attained at a later period by Lilybaeum.

Notwithstanding these accounts of its early importance and flourishing condition, the name of Motya is rarely mentioned in history until just before the period of its memorable siege. It is first mentioned by Hecataeus of Miletus,[12] and Thucydides notices it among the chief colonies of the Phoenicians in Sicily which existed at the time of the Athenian expedition, 415 BC.[13] A few years later (409 BC) when the Carthaginian army under Hannibal Mago landed at the promontory of Lilybaeum, that general laid up his fleet for security in the gulf around Motya, while he advanced with his land forces along the coast to attack Selinus.[14] After the fall of the latter city, we are told that Hermocrates, the Syracusan exile, who had established himself on its ruins with a numerous band of followers, laid waste the territories of Motya and Panormus;[15] and again during the second expedition of the Carthaginians under Hamilcar (407 BC), these two cities became the permanent station of the Carthaginian fleet.[16]

Siege of Motya

It was the important position to which Motya had thus attained that led Dionysius I of Syracuse to direct his principal efforts to its reduction, when in 397 BC he in his turn invaded the Carthaginian territory in Sicily. The citizens on the other hand, relying on succour from Carthage, made preparations for a vigorous resistance; and by cutting off the causeway which united them to the mainland, compelled Dionysius to have recourse to the tedious and laborious process of constructing a mound or mole of earth across the intervening space. Even when this was accomplished, and the military engines of Dionysius (among which the formidable catapult on this occasion made its appearance for the first time) were brought up to the walls, the Motyans continued a desperate resistance; and after the walls and towers were carried by the overwhelming forces of the enemy, still maintained the defence from street to street and from house to house. This obstinate struggle only increased the previous exasperation of the Sicilian Greeks against the Carthaginians; and when at length the troops of Dionysius made themselves masters of the city, they put the whole surviving population, men, women, and children, to the sword.[17]

After this, the Syracusan despot placed it in charge of a garrison under an officer named Biton, while his brother Leptines of Syracuse made it the station of his fleet. But the next spring (396 BC) Himilcon, the Carthaginian general, having landed at Panormus with a very large force, recovered possession of Motya with comparatively little difficulty.[18] Motya, however, was not destined to recover its former importance; for Himilcon, being apparently struck with the superior advantages of Lilybaeum, founded a new city on the promontory of that name, to which he transferred the few remaining inhabitants of Motya.[19]

From this period the latter altogether disappears from history; and the little islet on which it was built, has probably ever since, as now, been inhabited only by a few fishermen. By the time the Romans conquered Sicily, during the First Punic War (264–241 BC), Motya had been eclipsed by Lilybaeum.

It is a singular fact that, though we have no account of Motya having received any Greek population, or fallen into the hands of the Greeks before its conquest by Dionysius, there exist coins of the city with the Greek legend "ΜΟΤΥΑΙΟΝ". They are, however, of great rarity, and are apparently imitated from those of the neighboring city of Segesta.[20]

Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, Basilian monks settled on the island and renamed it San Pantaleo, and in 1888 was rediscovered by Joseph Whitaker.

Current situation

The site of Motya, on which earlier geographers were in much doubt, has been clearly identified and described by William Henry Smyth. Between the promontory of Lilybaeum (Capo Boéo) and that of Aegithallus (San Teodoro), the coast forms a deep bight, in front of which lies a long group of low rocky islets, called the Stagnone. Within these, and considerably nearer to the mainland, lies the small island formerly called San Pantaleo, on which the remains of an ancient city may still be distinctly traced. Fragments of the walls, with those of two gateways, still exist, and coins as well as pieces of ancient brick and pottery – the never failing indications of an ancient site – were found scattered throughout the island. The circuit of the latter does not exceed 2.5 km, and it is inhabited only by a few fishermen; but is not devoid of fertility.[21] The confined space on which the city was built agrees with the description of Diodorus that the houses were lofty and of solid construction, with narrow streets (στενωποί) between them, which facilitated the desperate defence of the inhabitants.[22]

The island of Mozia is owned and operated by the Whitaker Foundation (Palermo), famous for Marsala wines. Tours are available for the small museum, and the well-preserved ruins of a crossroads civilisation: in addition to the cultures mentioned above, Motian artifacts display Egyptian, Corinthian, Attic, Roman, Punic and Hellenic influences. The Tophet, a type of cemetery for the cremated remains of children, possibly (but not entirely proven) as sacrifice to Tanit or Ba‘al Hammon, is also well known. Many of the ancient residences are open to the public, with guided tours in English and Italian.

- Ruins of a part of the ancient city

Cothon of Motya

Cothon of Motya Silted up Cothon of Motya in 2013

Silted up Cothon of Motya in 2013 Submarine causeway

Submarine causeway

Archaeology

The beautiful Motya Charioteer sculpture found in 1979 is on display at the Giuseppe Whitaker museum. It is a rare example of a victor of a chariot race who must have been very wealthy in order to commission such a work. It was found built into Phoenician fortifications which were quickly erected before Dionysios I of Syracuse invaded and sacked Motya in 397 BC.

Its superb quality implies that it was made by a leading Greek artist in the period following their defeat of the Persians, but its style is unlike any other of this period. It is believed it must have been looted from a Greek city conquered by Carthage in 409-405 BC.[2]

In March 2006, archaeological digs uncovered rooms of a previously undiscovered house at one of the town's siege walls. The finds have shown that the town had a "thriving population long after it is commonly believed to have been destroyed by the Ancient Greeks." Discovered items include cooking pans, Phoenician-style vases, altars, and looms.[23]

In fiction

The 399 BC Battle of Motya, part of the war of Syracuse's tyrant Dionysios I against Carthage is a major event in the 1965 historical novel The Arrows of Hercules by L. Sprague de Camp.

References

Citations

- Motya: https://www.sitiarcheologiciditalia.it/en/motya/

- The Motya Charioteer and Pindar's "Isthmian 2" Malcolm Bell, III Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome Vol. 40 (1995), pp. 1-42

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-10-27. Retrieved 2017-01-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Motya, Museum Whitaker - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- Head & al. (1911), p. 877.

- Huss (1985), p. 571.

- Stephanus of Byzantium s. v.

- Diodorus Siculus xiv. 48.

- Thucydides vi. 2 ; Diod. xiv. 47.

- Thuc. l. c.

- Diod. xiv. 47.

- ap. Stephanus of Byzantium s. v..

- Thuc. vi. 2.

- Diod. xiii. 54, 61.

- Id. xiii. 63.

- Id. xiii. 88.

- Diod. xiv. 47-53.

- Ibid. 55.

- Diod. xxii. 10. p. 498.

- Eckhel, vol. i. p. 225.

- William Henry Smyth, Sicily, pp. 235, 236.

- Diod. xiv. 48, 51.

Bibliography

- Head, Barclay; et al. (1911), "Zeugitana", Historia Numorum (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 877–882.

- Huss, Werner (1985), Geschichte der Karthager, Munich: C.H. Beck. (in German)

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Motya. |

- Archaeological expedition to Motya, by Sapienza University of Rome

- Livius Picture Archive, including maps of the island and the lagoon

- Picture archive