Mjölnir

Mjölnir (/ˈmjɔːlnɪər/;[1] Old Norse: Mjǫllnir, IPA: [ˈmjɔlːnir])[2] is the hammer of Thor, the Norse god associated with thunder. Mjölnir is depicted in Norse mythology as one of the most fearsome and powerful weapons in existence, capable of leveling mountains. The Prose Edda relates how the hammer's characteristically short handle was due to a mistake during its manufacture.

Name

Old Norse Mjǫllnir [ˈmjɔlːnir] (later [ˈmjœlːnir]) is normally written miollnir in Old Icelandic early manuscripts from the 13th and 14th centuries.[2] The modern Icelandic form is Mjölnir, Faroese Mjølnir, Norwegian Mjølne, Danish Mjølner, Swedish Mjölner.

The name is derived from a Proto-Germanic form *meldunjaz, from the Germanic root of *malanan "to grind" (*melwan, Old Icelandic meldr, mjǫll, mjǫl "meal, flour"),[3] yielding an interpretation of "the grinder; crusher".

Additionally, there is a suggestion that the mythological "thunder weapon" being named after the word for "grindstone" is of considerable, Proto-Indo-European (if not Indo-Hittite) age; according to this suggestion, the divine thunder weapon (identified with lightning) of the storm god was imagined as a grindstone (Russian molot and possibly Hittite malatt- "sledgehammer, bludgeon"), reflected in Russian молния (molniya) and Welsh mellt "lightning" (possibly cognate with Old Norse mjuln "fire").[4]

In the Old Norse texts, Mjölnir is identified as hamarr "a hammer", a word that in Old Norse and some modern Norwegian dialects can mean "hammer" as well as "stone, rock, cliff", ultimately derived from an Indo-European word for "stone, stone tool", h₂éḱmō; as such it is cognate with Sanskrit aśman, meaning "stone, rock, stone tool; hammer" as well as "thunderbolt".[5]

Norse mythology

Origins in the Prose Edda

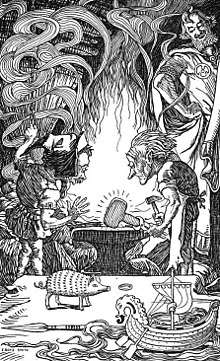

One account regarding the origins of Mjölnir, and arguably the most well known, is found in the Skáldskaparmál which is the second half of medieval Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda. The story depicts the creation of several iconic creature(s) and objects central to Norse mythology.

In this story, Loki the trickster finds himself in an especially mischievous mood and cuts off the gorgeous golden hair of Sif, the wife of Thor. On learning of Loki's trick, Thor is enraged and threatens to break every bone in his body. Loki pleads to Thor and asks for permission to go down to Svartalfheim, the cavernous home of the dwarves, to see if these master craftspeople could fashion a new head of hair for Sif. Thor is convinced and sends Loki to Svartalfheim.

On his arrival, Loki is able to complete his promise to Thor as The Sons Ivaldi forge not only a new head of hair for Sif, but also two other marvels: Skidbladnir, the best of all ships, and Gungnir, the deadliest of all spears. Having accomplished his task, Loki remains in the caves with the intention of causing mayhem. He approaches the brothers Brokkr and Sindri and taunts them, saying that he is sure the brothers could never forge three creations equal in caliber to the sons of Ivaldi, even betting his head against their lack of ability. Brokkr and Sindri, being prideful dwarves, accept the wager and begin their creation of three marvels.

The first begins with Sindri putting a pig's skin in the forge and telling Brokkr to work the bellows nonstop until his return. Loki, in disguise as a fly, comes and bites Brokkr on the arm to ensure the brothers lose their bet. Nevertheless, Brokkr continues to pump the bellows as ordered. When Sindri returns and pulls their creation from the fire, it is revealed to be a living boar with golden hair which they name Gullinbursti. This legendary creature gives off light in the dark and runs better than any horse, even through water or air.

Next, Sindri puts gold in the forge and gives Brokkr the same order. Loki comes again, still in the guise of a fly, and bites Brokkr's neck, this time twice as hard to ensure the brothers lose the bet. Brokkr, however, continues to work the bellows despite the pain. When Sindri returns they draw out a magnificent ring which they name Draupnir. From this ring, every ninth night, eight new golden rings of equal weight emerge.

Finally, Sindri puts iron in the forge and repeats his previous order once more. Loki comes a third time and bites Brokkr on the eyelid even harder, the bite being so deep that it draws blood. The blood runs into Brokkr's eyes and forces him to stop working the bellows just long enough to wipe his eyes. This time, when Sindri returns, he takes Mjölnir out of the forge. The handle is shorter than Sindri had originally planned which is the reason for the hammer's iconic imagery as a one handed weapon throughout Thor's religious iconography. Nevertheless, the pair are sure of the great worth of their three treasures and they make their way to Asgard to claim the wages due to them.

Loki makes it to the halls of the gods just before the dwarves and presents the marvels he has acquired. To Thor he gave Sif's new hair and the hammer Mjollnir. To Odin, the ring Draupnir and the spear Gungnir. Finally to Freyr he gives Skidbladnir and Gullinbursti.

As grateful as the gods were to receive these gifts they all agreed that Loki still owed his head to the brothers. When the dwarfs approach Loki with knives, the cunning god points out that he had promised them his head but not his neck, ultimately voiding their agreement. Brokkr and Sindri contented themselves with sewing Loki's mouth shut and returning to their forge.

Ceremonial and ritual significance

Though most famous for its use as a weapon, Mjolnir played a vital role in Norse religious practices and rituals. Its use in formal ceremonies to bless marriages, births, and funerals is described in several episodes within the Prose Edda.[6]

Historian and pagan studies scholar Hilda Ellis Davidson summarizes and explains the significance of Mjolnir in these rites, particularly marriage, stating:

The existence of this rite is assumed in the tale of Thor as a Transvestite, where the giants stole Thor’s hammer and he went to retrieve it by dressing as a bride to be married to one of the giants, knowing that the hammer would be presented during the ceremony. When it was presented, he seized it and promptly smashed the skulls of all of the giants in attendance. A Bronze Age rock carving from Scandinavia apparently depicts a couple being blessed by a larger figure holding a hammer, which indicates the considerable antiquity of this notion.

— Hilda Ellis Davidson, Gods and Myths of Northern Europe

Historian Gabriel Turville-Petre also suggests that Mjolnir's blessing was a possible means of imparting fertility to a couple. This is based on Thor's association with both agriculture and the fertilization of fields.[4]

Modern Pagans have emphasized the role of Mjolnir in their religious rituals and doctrine, though its primary function is to publicly signify faith (similarly to the way Christians wear or hang crucifixes).[7] While Norse in origin, Mjolnir's modern usage is not limited to Nordic pagans and has been utilized in Dutch pagan marriages, American pagan rituals, as well as the symbolic representation for all of Germanic heathenry.[8]

Continuation in the Poetic Edda

Thor possessed a formidable chariot, hreggs váfreiðar or “storm's hovering chariot”, which is drawn by two goats, Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr. A belt, Megingjörð, and iron gloves, Járngreipr, were used to lift Mjölnir. Mjölnir is the focal point of some of Thor's adventures.

This is clearly illustrated in a poem found in the Poetic Edda titled Þrymskviða. The myth relates that the giant, Þrymr, steals Mjölnir from Thor and then demands the goddess Freyja in exchange. Loki, the god notorious for his duplicity, conspires with the other Æsir to recover Mjölnir by disguising Thor as Freyja and presenting him as the "goddess" to Þrymr.

At a banquet Þrymr holds in honor of the impending union, Þrymr takes the bait. Unable to contain his passion for his new maiden with long, blond locks (and broad shoulders), Þrymr approaches the bride by placing Mjölnir on "her" lap; Thor rips off his disguise and destroys Þrymr and his giant cohorts.

Archaeological record

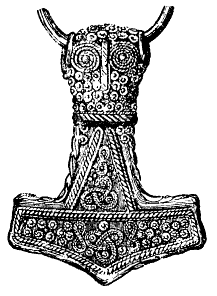

'Thor's hammer' pendants

As of 1997, about seventy-five early medieval Scandinavian pendants in the form of hammers had been found,[9] and more have since come to light.[10] Archaeologists have long inferred that these pendants are images of Thor's hammer.[9] Supporting evidence for this emerged for the first time in 2014, when the Købelev Runic-Thor's Hammer was found on the Danish island of Lolland. This is so far the only pendant bearing an inscription, which reads "hamr × is": here the mark × is a word-divider, making clear that the inscription means "[this] is [a] hammer".[11]

Christianisation of Thor's hammer pendants

A fairly large number of pendants in the 'Thor's hammer' style show a convergence with Christian crucifixes and therefore stand as evidence for the adaptation of traditional 'Thor's hammer' pendants to Christian culture as medieval Scandinavia converted to Christianity.[9] Hilda Ellis Davidson interpreted such images as signs of defiance, as unwilling Scandinavian converts to Christianity maintained their traditional symbols.[6]

Prominent examples include:

- An iron pendant, excavated in Yorkshire and dated to 1000 AD, bearing an uncial inscription preceded and followed by a cross, indicating a Christian owner repurposing traditional religious iconography to fit Christian symbolism.[12]

- The Trendgårdenstenen, a soapstone mold discovered in Trendgården, Denmark, dating to the tenth century. The mold has three chambers, two for crucifixes and one for a hammer. This particular mold is significant as it dates back to the height of Viking religious conversion but proves that one manufacturer was making objects fitting both traditional and Christian iconography.[13][14]

- National Museum of Iceland item 6077 is a pendant found in Foss in Hrunamannahreppur thought to be a variation on Thor's hammer.[15] It clearly bears a Christian-style cross, but its terminus is a wolf's head, and it has been viewed as integrating Christian and traditional imagery. As such it suggests the continuation of pagan beliefs in Iceland despite the country's conversion to Christianity in 1000.[16] Modern reproductions of the pendant are popular amongst certain neopagan groups and Viking enthusiasts for both religious and personal purposes.[17]

Stone carvings

Some early medieval image stones and runestones found in Denmark and southern Sweden bear an inscription of a hammer. Runestones depicting Thor's hammer include runestones U 1161 in Altuna, Sö 86 in Åby, Sö 111 in Stenkvista, Sö 140 in Jursta, Vg 113 in Lärkegapet, Öl 1 in Karlevi, DR 26 in Laeborg, DR 48 in Hanning, DR 120 in Spentrup, and DR 331 in Gårdstånga.[18][19] Other runestones included an inscription calling for Thor to safeguard the stone. For example, the stone of Virring in Denmark had the inscription þur uiki þisi kuml, which translates into English as "May Thor hallow this memorial." There are several examples of a similar inscription, each one asking for Thor to "hallow" or protect the specific artifact. Such inscriptions may have been in response to the Christians, who would ask for God's protection over their dead.[20]

Origins and comparanda

A precedent for Viking Age Mjolnir amulets have been documented in the migration period Alemanni, who took to wearing Roman "Hercules' Clubs" as symbols of Donar.[21] A possible remnant of these Donar amulets was recorded in 1897, as it was a custom of the Unterinn (South Tyrolian Alps) to incise a T-shape above front doors for protection against evil (especially storms).[22]

Similar hammers, such as Ukonvasara, were a common symbol of the god of thunder in other North European mythologies.

Relation to the swastika

In the early-modern Icelandic tradition of books of magic, the label Þórshamar ("Thor's hammer") is given to the image known in English as the swastika.[23][24][4]

It is uncertain whether this association existed earlier in Scandinavian culture, however. Images of the swastika are found fairly frequently in Scandinavia from as early as the Bronze Age (when they are commonly found alongside sunwheels and figures sometimes interpreted as sky gods).[4] The use of the symbol continued into the Viking Age, appearing for example on the Sæbø sword and the Snoldelev Stone. Some scholars have suggested that such swastika images are linked to ancient Scandinavian hammer images. In the words of Hilda Ellis Davidson, "it seems likely that the swastika as well as the hammer sign was connected with" Thor;[25] some nineteenth-century scholarship suggested that the hammer symbol was (in origin) a form of the swastika;[26] and this claim is repeated in some later work. Thus Henry Mayr-Harting speculated that "it may be that Thor's symbol, the swastika, originated as a device of hammers",[27] while Christopher R. Fee and David Adams Leeming claimed that "the image of Thor's weapon spinning end-over-end through the heavens is captured in art as a swastika symbol".[28]

Although these scholars do not discuss the basis for their association of the swastika with Thor and his hammer clearly, Ellis Davidson implies that the association was because, as she supposed, both symbols were associated with luck, prosperity, power, protection, as well as the sun and sky.[6][29]

The idea that Thor's hammer and the swastika are connected has been adopted by Neo-Nazis keen to link Nazi symbolism with medieval Norse culture;[30] both symbols feature, for example, in the logo of the explicitly Neo-Nazi band Absurd.[31]

Modern use

Most practitioners of Germanic Heathenry have adopted the symbol of Mjölnir as a symbol of faith, most commonly represented as pendants or other small jewelry. Renditions of Mjölnir are designed, crafted and sold by Germanic Heathen groups and individuals for public consumption as well as religious practice.

In May 2013 the "Hammer of Thor" was added to the list of United States Department of Veterans Affairs emblems for headstones and markers.[32][33][34]

Some Neo-Nazi groups have adopted the symbol and as such it is designated as a hate symbol by the Anti-Defamation League.[35] However, there is a movement among many Viking/pagan enthusiast groups to take back Mjölnir and other Norse symbols from the neo-nazis, and have said insignia removed from the Anti-Defamation League's listing.[36]

In the adventures of the Marvel Comics character Thor, based on the Norse god, a magical hammer similarly based on the original Mjölnir plays a major role. The hammer also has a spell written with Runic inscriptions engraved on it.

The coat of arms of the Torsås Municipality, Sweden, features a depiction of Mjölnir

The coat of arms of the Torsås Municipality, Sweden, features a depiction of Mjölnir The insignia of Tórshavn, capital of the Faroe Islands, features Thor's hammer

The insignia of Tórshavn, capital of the Faroe Islands, features Thor's hammer USVA Headstone Emblem of Mjölnir

USVA Headstone Emblem of Mjölnir Faroese stamp depicting the Viking Tróndur í Gøtu raising Mjölnir against Christianity

Faroese stamp depicting the Viking Tróndur í Gøtu raising Mjölnir against Christianity

See also

Notes

- "Mjolnir". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Normalized mjǫllnir in editions of GKS 2367 4º (Codex regius, early 14th century), 298, 9420; ed. Ólafur Halldórsson 1982, Finnur Jónsson 1931. Dictionary of Old Norse Prose (University of Copenhagen).

- Old Norse mala, Gothic, Old High German and Old Saxon malan, compared to Lithuanian malŭ, malti, Latvian maíu, Old Church Slavonic meljǫ, mlěti, Old Irish melim, Greek μύλλω (μυλjω), Latin molō "to grind"; Sanskrit mr̥ṇā́ti "to crush, smash, slay". Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch; Derksen (2008), Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Inherited Lexicon, p. 307.

- Turville-Petre, E.O.G. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidfeld and Nicoson, 1998. p. 84.

- Julius Pokorny, Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch (1959).

- Ellis Davidson, H.R. (1965). Gods And Myths Of Northern Europe, p. 83, ISBN 0-14-013627-4

- Strutynski, Udo (March 1984). "The Survival of Indo-European Mythology in Germanic Legendry: Toward an Interdisciplinary Nexus". The Journal of American Folklore. 97 (383): 43–56. doi:10.2307/540395. JSTOR 540395.

- Minkjan, Hanneke (December 2012). "Meeting Freya and the Cailleich, Celebrating Life and Death: Rites of Passage beyond Dutch Contemporary Pagan Community". The Pomegranate.

- E. Wamers, 'Hammer und Kreuz: Typologische Aspekte einer nordeuropäischen Amulettsitte aus der Zeit des Glaubenswechsels', in Rom und Byzanz im Norden: Mission und Glaubenswechsel im Ostseeraum während des 8.-14. Jahrhunderts. Internationale Fachkonferenz der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Verbindung mit der Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Litertur, Mainz Kiel 18.-25. September 1994, ed. by M. Müller-Wille, 2 vols. (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1997), I, 83-107.

- "Denmark Vikings-Era Discoveries". Archived from the original on 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

- Peter Pentz, 'Viking Art, Snorri Sturluson and Some Recent Metal Detector Finds', Fornvännen: Journal of swedish Antiquarian Research, 113 (2018), 17-33 (p. 22).

- "23. Religions - the Schoyen Collection". Archived from the original on 2007-07-17. Retrieved 2007-12-13.Schoyen Collection, MS 1708 Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- This has been interpreted as the property of a craftsman "hedging his bets" by catering to both a Christian and a pagan clientele."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-06-29. Retrieved 2007-12-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Simek, Rudolf (1993). A Dictionary of Northern Mythology. Cambridge, England: D.S. Brewer.

- Þór Magnússon, '[timarit.is/view_page_init.jsp?pageId=2052554&issId=140036&lang=da Bátkumlið í Vatnsdal í Patreksfirði]', Árbók Hins íslenzka fornleifafélags, 63 (1966), 5-32 (p. 18).

- Heath, Ian (1985). The Vikings (Elite). Osprey Publishing: Reprint Edition. ISBN 978-0850455656.

- Popular Nordic jewelry sites offer exact replicas and various Viking enthusiast blogs reference the pendant. https://thornews.com/2014/03/17/thors-hammers-disguised-as-crucifixes/; https://www.seiyaku.com/customs/crosses/thor.html.

- Holtgård, Anders (1998). "Runeninschriften und Runendenkmäler als Quellen der Religionsgeschichte". In Düwel, Klaus; Nowak, Sean (eds.). Runeninschriften als Quellen Interdisziplinärer Forschung: Abhandlungen des Vierten Internationalen Symposiums über Runen und Runeninschriften in Göttingen vom 4–9 August 1995. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 727. ISBN 3-11-015455-2. Archived from the original on 10 November 2015.

- McKinnell, John; Simek, Rudolf; Düwel, Klaus (2004). "Gods and Mythological Beings in the Younger Futhark". Runes, Magic and Religion: A Sourcebook (PDF). Vienna: Fassbaender. pp. 116–133. ISBN 3-900538-81-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-18.

- Turville-Petre, E.O.G. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964. p. 82–83.

- Werner: "Herkuleskeule und Donar-Amulett". in: Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz, Nr. 11, Mainz, 1966.

- Joh. Adolf Heyl, Volkssagen, Bräuche und Meinungen aus Tirol (Brixen: Verlag der Buchhandlung des Kath.-polit. Pressvereins, 1897), p. 804.

- Flowers, Stephen (September 1989). The Galdrabók: An Icelandic Grimoire. York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser. p. 39. ISBN 0-87728-685-X.

- MacLeod, Mindy, and Bernard Mees (2006). Runic Amulets and Magic Objects. p. 252.

- H. R. Ellis Davidson, Gods and Myths of Northern Europe (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1964), pp. 82-83.

- William Thornton Parker, "The Swastika: A Prophetic Symbol", Open Court (1907), 539-546 (p. 543).

- Henry Mayr-Harting, The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England Archived 2016-05-27 at the Wayback Machine (1991), p. 26. Cf. p. 3: "many cremation pots of the early Anglo-Saxons have the swastika sign marked on them, and in some the swastikas seems to be confronted with serpents or dragons in a decorative design. This is a clear reference to the greatest of all Thor's struggles, that with the World Serpent which lay coiled round the earth".

- Christopher R. Fee, David Adams Leeming, Gods, Heroes, and Kings: The Battle for Mythic Britain (2001), p. 31.

- Cf. Green, Miranda (1989). Symbol and Image in Celtic Religious Art. pp. 4, 154.

- Joanne Mundorf & Guo-Ming Chen, 'Transculturation of Visual Signs: A Case Analysis of the Swastika', Intercultural Communication Studies, 25.2 (2006), 33-48 (p. 35).

- Lindsey L. Turnbull, 'The Evolution of the Swastika: From Symbol of Peace to Tool of Hate' (Honors thesis, University of Central Floria, 2010), p. 63.

- "National Cemetery Administration: Available Emblems of Belief for Placement on Government Headstones and Markers". U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

55 – Hammer of Thor

- Elysia. "Hammer of Thor now VA accepted symbol of faith". Llewellyn. Archived from the original on 12 June 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- Brownlee, John (July 9, 2013). "How Thor's Hammer Made Its Way Onto Soldiers' Headstones: Thor's hammer, Mjölnir, is a weapon of honor and virtue, making it an appealing icon for American soldiers. But its path to becoming an acceptable headstone symbol was anything but easy". www.fastcodesign.com. Archived from the original on June 14, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

In Norse mythology, Mjölnir (which means "crusher" or "grinder") is a fearsome weapon that can destroy entire mountains with a single blow.... On May 10, 2013, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs quietly made an update to its official list of approved emblems, adding Thor's hammer, Mjölnir.

- "Thor's Hammer". Anti-Defamation League. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- "We can't let racists re-define Viking culture". The Local.se. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

References

- Turville-Petre, E.O.G. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Archaeological record of Mjöllnir. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mjöllnir. |

| Look up Mjollnir in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |