Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād

Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād (c. 1450 – c. 1535), also known as Kamal al-din Bihzad or Kamaleddin Behzad (Persian: کمالالدین بهزاد), was a Persian painter and head of the royal ateliers in Herat and Tabriz during the late Timurid and early Safavid Persian periods.

Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1450 |

| Died | 1535 (aged 85) |

| Occupation | painter |

| Era | Medieval Period, Late Timurid, Early Safavid Empire |

Notable work | Painting photographs of Jami, Sultan Husayn Mirza Bayqara, Ali-Shir Nava'i, Ismail I |

Biography

He was born and lived most of his life in Herat, a city in the western Afghanistan which was an important center of trade and the cultural and economic capital of the Timurid Empire. An orphan, he was raised by the prominent painter Mirak Naqqash, and was a protégé of Mir Ali Shir Nava'i. His major patrons in Herat were the Timurid sultan Husayn Bayqarah (ruled 1469–1506) and other amirs in his circle. After the fall of the Hamad, he was employed by Shah Ismail I Safavi in Tabriz, where, as director of the royal atelier, he had a decisive impact on the development of later Safavid painting. Behzad died in 1535, and his tomb is located in Herat, in Saeede Mukhtar which is located in north of Herat city on the top of a hill. A statue of Behzad is placed in 2-Kamal Tomb.

Career and style

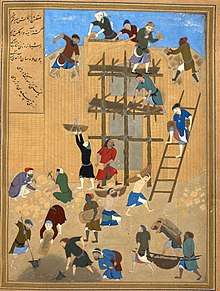

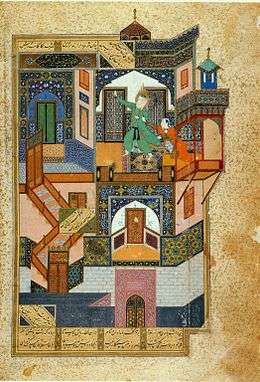

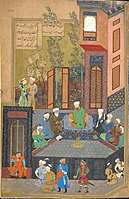

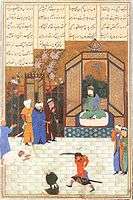

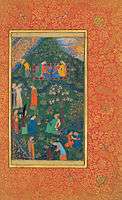

Behzad is the most famous of Persian miniature painters, though he is more accurately understood as the director of a workshop (or kitabkhāna) producing manuscript illuminations in a style he conceived.[1][2][3] Persian painting of the period frequently uses an arrangement of geometric architectural elements as the structural or compositional context in which the figures are arranged.

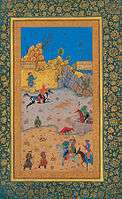

Behzad is equally skilled with the organic areas of landscape, but where he uses the traditional geometric style Behzad stretches that compositional device in a couple ways. One is that he often uses open, unpatterned empty areas around which action moves. Also he pins his compositions to a mastery at moving the eye of the observer around the picture plane in a quirky organic flow. The gestures of figures and objects are not only uniquely natural, expressive and active, they are arranged to keep moving the eye throughout the picture plane.

He uses value (dark-light contrast) more emphatically, and skillfully than other medieval miniaturists. Another quality common to his work is narrative playfulness: the almost hidden eye and partial face of Bahram as he peers out the blinds to watch the frolicking girls in the pool below, the upright goat that looks like a demon along the edge of the horizon in a story about an old woman confronting the sins of Sanjar, the amazing cosmopolitan variety of humans working on the wall in the sample image.

This surprising individuality of character and narrative creativity are some qualities that distinguish Bezhad's works and that match their literary intent. Behzad also uses Sufi symbolism and symbolic colour to convey meaning. He introduced greater naturalism to Persian painting, particularly in the depiction of more individualised figures and the use of realistic gestures and expressions.

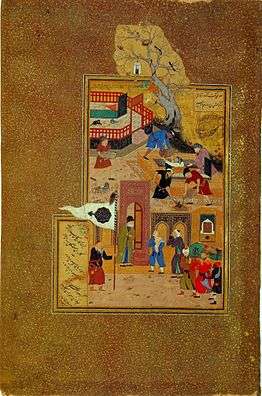

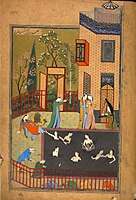

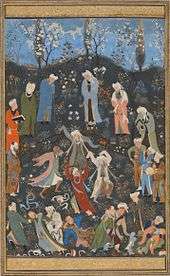

Behzad's most famous works include "The Seduction of Yusuf" from Sa'di's Bustan of 1488, and paintings from the British Library's Nizami manuscript of 1494-95 - particularly scenes from Layla and Majnun and the Haft Paykar (see accompanying image). The attribution of specific paintings to Behzad himself is often problematic (and, many academics would now argue, unimportant),[1] but the majority of works commonly attributed to him date from 1488 to 1495.

Bihzad in literature

Bihzad is mentioned throughout Orhan Pamuk's novel, My Name is Red, in which a workshop of Ottoman miniaturists regards him as one of the greatest Persian miniaturists.

Gallery

A miniature painting by Bihzad illustrating the funeral of the elderly Attar of Nishapur after he was held captive and killed by a Mongol invader.

A miniature painting by Bihzad illustrating the funeral of the elderly Attar of Nishapur after he was held captive and killed by a Mongol invader. Yusef and Zuleykha

Yusef and Zuleykha A miniature painting from the Iskandarnama

A miniature painting from the Iskandarnama A miniature painting from the Iskandarnama

A miniature painting from the Iskandarnama The hunting ground.

The hunting ground. Beheading of a King

Beheading of a King Sultan Hussein

Sultan Hussein.jpg) Timur granting audience on the occasion of his accession

Timur granting audience on the occasion of his accession Dancing dervishes (c. 1480/1490)

Dancing dervishes (c. 1480/1490)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kamal-ud-din Bihzad. |

- Persian miniature

- List of Persian painters

- (in French) Behzad on the French Wikipedia

- Begzada

Notes

- Roxburgh, David J., “Kamal al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting,” Muqarnas, Vol. XVII, 2000, pp. 119-146.

- Lentz, Thomas, “Changing Worlds: Bihzad and the New Painting,” Persian Masters: Five Centuries of Painting, ed., Sheila R. Canby, Bombay, 1990, pp. 39–54.

- Lentz, Thomas, and Lowry, Glenn D., Timur and the Princely Vision, Los Angeles, 1989.

References

- Balafrej, Lamia. The Making of the Artist in Late Timurid Painting, Edinburgh University Press, 2019, ISBN 9781474437431

- Brend, Barbara, Islamic Art, London, 1991.

- Chapman, Sarah, “Mathematics and Meaning in the Structure and Composition of Timurid Miniature Painting”, Persica, Vol. XIX, 2003, pp. 33–68.

- Grabar, Oleg, "Mostly Miniatures: An introduction to Persion Painting" Princeton, 2000

- Gray, Basil, Persian Painting, London, 1977.

- Hillenbrand, Robert, Islamic Art and Architecture, London, 1999.

- Lentz, Thomas, and Lowry, Glenn D., Timur and the Princely Vision, Los Angeles, 1989.

- Lentz, Thomas, “Changing Worlds: Bihzad and the New Painting,” Persian Masters: Five Centuries of Painting, ed., Sheila R. Canby, Bombay, 1990, pp. 39–54.

- Milstein, Rachel, “Sufi Elements in Late Fifteenth Century Herat Painting”, Studies in Memory of Gaston Wiet, ed., M. Rosen-Ayalon, Jerusalem, 1977, pp. 357–70.

- Rice, David Talbot, Islamic Art, 2nd ed., London, 1975.

- Rice, David Talbot, Islamic Painting: a Survey, Edinburgh, 1971.

- Robinson, Basil W., Fifteenth Century Persian Painting: Problems and Issues, New York, 1991.

- Roxburgh, David J., “Kamal al-Din Bihzad and Authorship in Persianate Painting,” Muqarnas, Vol. XVII, 2000, pp. 119–146.