Minamoto clan

Minamoto (源) was one of the surnames bestowed by the Emperors of Japan upon members of the imperial family who were excluded from the line of succession and demoted into the ranks of the nobility from 1192 to 1333.[1] The practice was most prevalent during the Heian period (794–1185 AD), although its last occurrence was during the Sengoku period. The Taira were another such offshoot of the imperial dynasty, making both clans distant relatives. The Minamoto clan is also called the Genji (源氏), or less frequently, the Genke (源家), using the on'yomi reading for Minamoto.

| Minamoto clan 源氏 | |

|---|---|

The emblem (mon) of the Minamoto clan | |

| Home province | Various |

| Parent house | |

| Titles | Various |

| Founder | Minamoto no Makoto |

| Cadet branches |

|

The Minamoto were one of four great clans that dominated Japanese politics during the Heian period — the other three were the Fujiwara, the Taira, and the Tachibana.

History

The first emperor to grant the surname Minamoto to his children was Emperor Saga, who reportedly had 49 children, resulting in a significant financial burden on the imperial household. In order to alleviate some of the pressure of supporting his unusually many offspring, he made many of his sons and daughters nobles instead of royals. He chose the word minamoto (meaning "origin") for their new surname in order to signify that the new clan shared the same origins as the royal family. Afterwards, Emperor Seiwa, Emperor Murakami, Emperor Uda, and Emperor Daigo, among others, also gave their non-heir sons or daughters the name Minamoto. These specific hereditary lines coming from different emperors developed into specific clans referred to by the emperor's name followed by Genji (e.g. Seiwa Genji). According to some sources, the first to be given the name Minamoto was Minamoto no Makoto, seventh son of Emperor Saga.[2]

The most prominent of the several Minamoto families, the Seiwa Genji, descended from Minamoto no Tsunemoto (897–961), a grandson of Emperor Seiwa. Tsunemoto went to the provinces and became the founder of a major warrior dynasty. Minamoto no Mitsunaka (912–997) formed an alliance with the Fujiwara. Thereafter the Fujiwara frequently called upon the Minamoto to restore order in the capital, Heian-Kyō (modern Kyōto).[3]:240–241

Mitsunaka's eldest son, Minamoto no Yorimitsu (948–1021), became the protégé of Fujiwara no Michinaga; another son, Minamoto no Yorinobu (968–1048) suppressed the rebellion of Taira no Tadatsune in 1032. Yorinobu's son, Minamoto no Yoriyoshi (988–1075), and grandson, Minamoto no Yoshiie (1039–1106), pacified most of northeastern Japan between 1051 and 1087.[3]

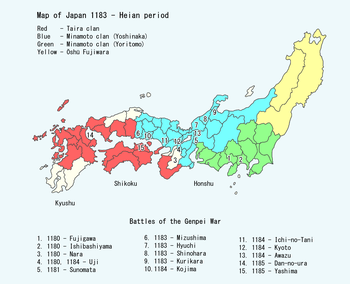

The Seiwa Genji's fortunes declined in the Hōgen Rebellion (1156), when the Taira executed much of the line, including Minamoto no Tameyoshi. During the Heiji Disturbance (1160), the head of the Seiwa Genji, Minamoto no Yoshitomo, died in battle.[3]:256–258 Taira no Kiyomori seized power in Kyoto by forging an alliance with the retired emperors Go-Shirakawa and Toba and infiltrating the kuge. He sent Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147–1199), the third son of Minamoto no Yoshimoto of the Seiwa Genji, into exile. In 1180, during the Genpei War, Yoritomo mounted a full-scale rebellion against the Taira rule, culminating in the destruction of the Taira and the subjugation of eastern Japan within five years. In 1192 he received the title shōgun and set up the first bakufu at Kamakura.[3]:275,259–260, 289–305,331

The later Ashikaga (founders of the Ashikaga shogunate), Nitta, and Takeda clans claim descent from the Seiwa Genji.

The protagonist of the classical Japanese novel The Tale of Genji, Hikaru Genji, was bestowed the name Minamoto for political reasons by his father the emperor and was delegated to civilian life and a career as an imperial officer.

The Genpei War is also the subject of the early Japanese epic The Tale of the Heike (Heike Monogatari).

Members of the Minamoto clan (Genji Clan)

Even within royalty there was a distinction between princes with the title shinnō (親王) ("[having the] ability to advance", i.e., eligible to become the new Emperor), who could ascend to the throne, and princes with the title ō (王) ("great" or "major"), who were not members of the line of imperial succession but nevertheless remained members of the royal class (and therefore outranked members of Minamoto clans). The bestowing of the Minamoto name on a (theretofore-)prince or his descendants excluded them from the royal class altogether, thereby operating as a reduction in legal and social rank even for ō-princes not previously in the line of succession.

Many later clans were formed by members of the Minamoto clan, and in many early cases, progenitors of these clans are known by either family name. There are also known monks of Minamoto descent; these are often noted in genealogies but did not carry the clan name (in favor of a dharma name).

There were 21 branches of the clan, each named after the emperor from whom it descended. Some of these lineages were populous, but a few produced no descendants.

Saga Genji

The Saga Genji were descendants of Emperor Saga. As Saga had many children, many were bestowed the uji Minamoto, declassing them from imperial succession. Among his sons, Makoto, Tokiwa, and Tōru took the position of Minister of the Left (sadaijin); they were among the most powerful in the Imperial Court in the early Heian period. Some of Tōru's descendants in particular settled the provinces and formed buke. Clans such as the Watanabe, Matsuura, and Kamachi descended from the Saga Genji.

Noted Saga Genji and descendants include:

- Makoto, seventh son of the Emperor

- Hiromu, eighth son of the Emperor

- Hitoshi, grandson of Hiromu

- Tokiwa, son of the Emperor

- Okoru, first son of Tokiwa

- Sadamu, son of the Emperor

- Shitagō, great-grandson of Sadamu

- Hiroshi, son of the Emperor

- Tōru, son of the Emperor

- Anbō (secular name Minamoto no Shitagō), great-grandson of Tōru

- Watanabe no Tsuna (formally a Minamoto, who resided at Watanabe in Settsu province, and took the name of the place), great-great-grandson of Tōru

- Matsuura Hisashi, grandson of Tsuna

- Koreshige, grandson of Tōru

- Mitsusue, great-great-grandson of Koreshige

- Tsutomu, son of the Emperor

- Hiraku, son of the Emperor

History records that at least three of Emperor Saga's daughters were also made Minamoto (Kiyohime, Sadahime, and Yoshihime), but few records concerning his daughters are known.

Ninmyō Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Ninmyō. His sons Masaru and Hikaru were udaijin. Among Hikaru's descendants was Minamoto no Atsushi, adoptive father of the Saga Genji's Tsuna and father of the Seiwa Genji's Mitsunaka's wife.

Montoku Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Montoku. Among them, Yoshiari was a sadaijin, and among his descendants were the Sakado clan who were Hokumen no Bushi.

Seiwa Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Seiwa. The most numerous of them were those descended from Tsunemoto, son of Prince Sadazumi. Hachimantarō Yoshiie of the Kawachi Genji was a leader of a buke. His descendants set up the Kamakura shogunate, making his a prestigious pedigree claimed by many buke, particularly for the direct descendants in the Ashikaga clan (that set up the Ashikaga shogunate) and the rival Nitta clan. Centuries later, Tokugawa Ieyasu would claim descent from the Seiwa Genji by way of the Nitta clan.

Yōzei Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Yōzei. While Tsunemoto is termed the ancestor of the Seiwa Genji, there is evidence (rediscovered in the late 19th century by Hoshino Hisashi) suggesting that he was actually the grandson of Yōzei rather than of Seiwa. This theory is not widely accepted as fact, but as Yōzei was deposed for reprehensible behavior, there would have been a compelling motive to claim descent from more auspicious origins if it were the case.

Kōkō Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Kōkō. The great-grandson of his firstborn Prince Koretada, Kōshō, was the ancestor of a line of busshi, from which various styles of Buddhist sculpture emerged. Kōshō's grandson Kakujo established the Shichijō Bussho workshop.

Uda Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Uda. Two sons of Prince Atsumi, Masanobu and Shigenobu became sadaijin. Masanobu's children in particular flourished, forming five dōjō houses as kuge, and as buke the Sasaki clan of the Ōmi Genji, and the Izumo Genji.

Daigo Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Daigo. His son Takaakira became a sadaijin, but his downfall came during the Anna incident. Takaakira's descendants include the Okamoto and Kawajiri clans. Daigo's grandson Hiromasa was a reputed musician.

Murakami Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Murakami. His grandson Morofusa was an udaijin and had many descendants, among them several houses of dōjō kuge. Until the Ashikaga clan took it during the Muromachi period, the title of Genji no Chōja always fell to one of Morofusa's progeny.

Reizei Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Reizei. Though they are included among the listing of 21 Genji lineages, no concrete record of the names of his descendants made Minamoto is known to survive.

Kazan Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Kazan. They became the dōjō Shirakawa family, which headed the Jingi-kan for centuries, responsible for the centralized aspects of Shinto.

Sanjō Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Sanjō's son Prince Atsuakira. Starting with one of them, Michisue, the position of Ōkimi-no-kami (chief genealogist of the imperial family) in the Ministry of the Imperial Household was passed down hereditarily.

Go-Sanjō Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Go-Sanjō's son Prince Sukehito. Sukehito's son Arihito was a sadaijin. Minamoto no Yoritomo's vassal Tashiro Nobutsuna, who appears in the Tale of the Heike, was allegedly Arihito's grandson (according to the Genpei Jōsuiki).

Go-Shirakawa Genji

This line consisted solely of Emperor Go-Shirakawa son Mochihito-ō (Takakura-no-Miya). As part of the succession dispute that led to the opening hostilities of the Genpei War, he was declassed (renamed "Minamoto no Mochimitsu") and exiled.

Juntoku Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Juntoku's sons Tadanari-ō and Prince Yoshimune. The latter's grandson Yoshinari rose to sadaijin with the help of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu.

Go-Saga Genji

This line consisted solely of Emperor Go-Saga's grandson Prince Koreyasu. Koreyasu-ō was installed as a puppet shōgun (the seventh of the Kamakura shogunate) at a young age, and was renamed "Minamoto no Koreyasu" a few years later. After he was deposed, he regained royal status, and became a monk soon after, thereby losing the Minamoto name.

Go-Fusakusa Genji

These were descendants of Emperor Go-Fusakusa's son Prince Hisaaki (the eighth shōgun of the Kamakura shogunate). Hisaaki's sons Prince Morikuni (the next shōgun) and Prince Hisayoshi were made Minamoto. Hisayoshi's adopted "nephew" (actually Nijō Michihira's son) Muneaki became a gon-dainagon (acting dainagon).

Ōgimachi Genji

These were non-royal descendants of Emperor Ōgimachi. At first they were buke, but they later became dōjō-ke, the Hirohata family.

References

- "...the Minamoto (1192-1333)" Warrior Rule in Japan, page 11. Cambridge University Press.

- Frederic, Louis (2002). Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Sansom, George (1958). A History of Japan to 1334. Stanford University Press. pp. 241–242, 247–252. ISBN 0804705232.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Minamoto clan. |