Michael John O'Leary

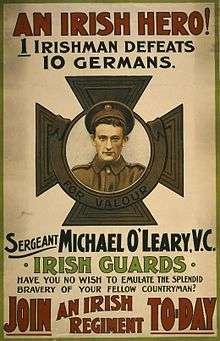

Major Michael John O'Leary VC (29 September 1890 – 2 August 1961) was an Irish recipient of the Victoria Cross, the most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces. O'Leary achieved his award for single-handedly charging and destroying two German barricades defended by machine gun positions near the French village of Cuinchy, in a localised operation on the Western Front during the First World War.

Michael John O'Leary | |

|---|---|

Michael O'Leary, VC. | |

| Born | 29 September 1890 Inchigeela, Macroom, County Cork |

| Died | 1 August 1961 (aged 70) Islington, London, England |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Royal Navy British Army |

| Years of service | 1906 – 1910 (Royal Navy) 1910 – 1913, 1914 – 1921, 1939 – 1945 (British Army) |

| Rank | Major |

| Unit | Irish Guards Connaught Rangers Middlesex Regiment |

| Battles/wars | First World War Second World War |

| Awards | Victoria Cross Mentioned in Despatches Cross of St George, third class (Russian Empire) |

At the time of his action, O'Leary was a nine-year veteran of the British armed forces and by the time he retired from the British Army in 1921, he had reached the rank of lieutenant. He served in the army again during the Second World War, although his later service was blighted by periods of ill-health. At his final retirement from the military in 1945, O'Leary was an Army major in command of a prisoner of war camp. Between the wars, O'Leary spent many years employed as a police officer in Canada and is sometimes considered to be a Canadian recipient of the Victoria Cross. Following the Second World War he worked as a building contractor in London, where he died in 1961.

Early life

O'Leary was born in 1890, one of four children of Daniel and Margaret O'Leary, who owned a farm at Inchigeela, near Macroom in County Cork, Ireland. Daniel O'Leary was a fervent Irish nationalist and keen sportsman who participated in competitive weightlifting and football. Aged 16 and unwilling to continue to work on his parent's land, Michael O'Leary joined the Royal Navy, serving at the shore establishment HMS Vivid at Devonport for several years until rheumatism in his knees forced his departure from the service. Within a few months however, O'Leary had again tired of the farm and joined the Irish Guards regiment of the British Army.[1]

O'Leary served three years with the Irish Guards, leaving in August 1913 to join the Royal Northwest Mounted Police (RNWMP) in Saskatchewan, Canada. Operating from Regina, Constable O'Leary was soon commended for his bravery in capturing two criminals following a two-hour gunbattle, for which service he was presented with a gold ring.[1] At the outbreak of the First World War in Europe during August 1914, O'Leary was given permission to leave the RNWMP and return to Britain in order to rejoin the army as an active reservist. On 22 October, O'Leary was mobilized and on 23 November he joined his regiment in France, then fighting with the British Expeditionary Force, entrenched in Flanders.

First World War service

_(14577632219).jpg)

During December 1914, O'Leary saw heavy fighting with the Irish Guards and was Mentioned in Despatches and subsequently promoted to lance corporal on 5 January 1915. Three weeks later, on 30 January, the Irish Guards were ordered to prepare for an attack on German positions near Cuinchy on the La Bassée Canal, a response to a successful German operation in the area five days before. The Germans attacked first however, and on the morning of 1 February seized a stretch of canal embankment on the western end of the 2nd Brigade line from a company of Coldstream Guards. This section, known as the Hollow, was tactically important as it defended a culvert that passed underneath a railway embankment.[2] 4 Company of Irish Guards, originally in reserve, were tasked with joining the Coldstream Guards in retaking the position at 04:00, but the attack was met with heavy machine gun fire and most of the assault party, including all of the Irish Guards officers, were killed or wounded.[3]

To replace these officers, Second Lieutenant Innes of 1 Company was ordered forward to gather the survivors and withdraw, forming up at a barricade on the edge of the Hollow. Innes regrouped the survivors and, following a heavy bombardment from supporting artillery and with his own company providing covering fire, assisted the Coldstream Guards in a second attack at 10:15.[2] Weighed down with entrenching equipment, the attacking Coldstream Guardsmen faltered and began to suffer heavy casualties. Innes too came under heavy fire from a German barricade to their front equipped with a machine gun.[4]

O'Leary had been serving as Innes's orderly, and had joined him in the operations earlier in the morning and again in the second attack. Charging past the rest of the assault party, O'Leary closed with the first German barricade at the top of the railway embankment and fired five shots, killing the gun's crew. Continuing forward, O'Leary confronted a second barricade, also armed with a machine gun 60 yards (55 m) further on and again mounted the railway embankment, to avoid the marshy ground on either side. The Germans spotted his approach, but could not bring their gun to bear on him before he opened fire, killing three soldiers and capturing two others after he ran out of ammunition.[4] Reportedly, O'Leary had made his advance on the second barricade "intent upon killing another German to whom he had taken a dislike".[2]

Having disabled both guns and enabled the recapture of the British position, O'Leary then returned to his unit with his prisoners, apparently "as cool as if he had been for a walk in the park."[1] For his actions, O'Leary received a battlefield promotion to sergeant on 4 February and was recommended for the Victoria Cross, which was gazetted on 16 February:

No. 3556 Lance-Corporal Michael O'Leary, 1st Battalion, Irish Guards

For conspicuous bravery at Cuinchy on the 1st February, 1915. When forming one of the storming party which advanced against the enemy's barricades he rushed to the front and himself killed five Germans who were holding the first barricade, after which he attacked a second barricade, about 60 yards further on, which he captured, after killing three of the enemy and making prisoners of two more. Lance-Corporal O'Leary thus practically captured the enemy's position by himself and prevented the attacking party from being fired upon.

The London Gazette, 16 February 1915[5]

Later war service

Returning to Britain to receive his medal from King George V at Buckingham Palace on 22 June 1915, O'Leary was given a grand reception attended by thousands of Londoners in Hyde Park on 10 July. He was also the subject of much patriotic writing, including a poem in the Daily Mail and the short play O'Flaherty V.C. by George Bernard Shaw.[1] Tributes came from numerous prominent figures of the day, including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who said that "No writer in fiction would dare to fasten such an achievement on any of his characters, but the Irish have always had a reputation of being wonderful fighters, and Lance-Corporal Michael O’Leary is clearly one of them." and Thomas Scanlan who said: "I heard early this week of the great achievements of the Irish Guards. All Ireland is proud of O’Leary. He fully deserves the high honour that has been conferred upon him. Ireland is grateful to him."[6] His reception was repeated in Macroom when he visited Ireland, with crowds turning out to applaud him. Daniel O'Leary was interviewed in a local newspaper regarding his son's exploit but was reportedly unimpressed, commenting: "I am surprised he didn't do more. I often laid out twenty men myself with a stick coming from Macroom Fair, and it is a bad trial of Mick that he could kill only eight, and he having a rifle and bayonet."[7]

O'Leary was further rewarded for his service, being advanced to a commissioned rank as a second lieutenant with the Connaught Rangers,[8] and he was also presented with a Russian decoration, the Cross of St. George (third class).[9] Despite his popularity with the crowds in London and Macroom, he was jeered by Ulster Volunteers at a recruitment drive in Ballaghaderrin during the autumn of 1915. This treatment caused such a scandal that it was raised in the Houses of Parliament in December.[7]

In 1916, O'Leary travelled to Salonika with the 5th battalion of the Connaught Rangers to serve in the Balkans campaign, remaining in theatre until the end of the war, following which he was stationed in Dover with the 2nd battalion until demobilised in 1921.[7] During his service in the Balkans, O'Leary contracted malaria, which was to have severe negative effects on his health for the rest of his life.[10]

O'Leary was in the same regiment as the British actor Stanley Holloway and they served together in France. After the war ended, they remained close friends and Holloway often stayed in The May Fair Hotel where O'Leary worked as a concierge.[11]

Later life

Leaving his wife Greta and their two children in Britain, O'Leary returned to Canada in March 1921 with the purported intention of rejoining the RNWMP, newly renamed the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. For unknown reasons, this plan came to nothing and after some months giving lectures on his war service and working in a publishing house, O'Leary joined the Ontario Provincial Police, charged with enforcing the prohibition laws. In 1924, with his family recently arrived from England, O'Leary left the Ontario police force and became a police sergeant with the Michigan Central Railway in Bridgeburg, Ontario, receiving £33 a month.[7]

In 1925, O'Leary was the subject of several scandals, being arrested for smuggling illegal immigrants and later for irregularities in his investigations. Although he was acquitted both times, he spent a week in prison following the second arrest and lost his job with the railway.[7] Several months later, the municipal authorities in Hamilton, Ontario loaned him £70 to pay for him and his family to return to Ireland. Although his family sailed on the SS Leticia, O'Leary remained in Ontario, working with the attorney general's office.[10]

With his health in serious decline, the British Legion arranged for O'Leary to return to Britain and work in their poppy factory. By 1932, O'Leary was living in Southborne Avenue in Colindale, had regained his health and found employment as a commissionaire at The May Fair Hotel in London, at which he was involved in charitable events for wounded servicemen. With the mobilisation of the British Army in 1939, O'Leary returned to military service as a captain in the Middlesex Regiment. O'Leary was sent to France as part of the British Expeditionary Force but had returned to Britain before the Battle of France due to a recurrence of his malaria.[10]

No longer fit for full active service, O'Leary was transferred to the Pioneer Corps and took command of a prisoner of war camp in Southern England. In 1945, he was discharged from the military as unfit for duty on medical grounds as a major and found work as a building contractor, in which career he remained until his retirement in 1954. Two of O'Leary's sons had also served in the military during the war, with both receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross for their actions. As a Victoria Cross recipient, O'Leary joined the VE day parade in 1946, but at the 1956 Centenary VC review his place was taken by an imposter travelling in a bath chair. With his health again declining, O'Leary moved to Limesdale Gardens in Edgware shortly before his death in 1961 at the Whittington Hospital in Islington.[10]

O'Leary was buried at Mill Hill Cemetery following a funeral service at the Roman Catholic Annunciation Church in Burnt Oak which was attended by an honour guard from the Irish Guards and six of his children. His medals were later presented to the Irish Guards, and are on display at the Regimental Headquarters.[12] He is also remembered in his birthplace, the macroom-online website listing him as a prominent citizen and states that "while many might consider he was fighting with the wrong army, in the wrong war, he was nevertheless a very brave, resourceful and capable soldieer [sic] who deserved the honours bestowed upon him."[13]

Notes

- Batchelor & Matson, p. 3

- Kipling, p. 76–77

- Batchelor & Matson, p. 1

- Batchelor & Matson, p. 2

- "No. 29074". The London Gazette (Supplement). 16 February 1915. p. 1700.

- Michael O'Leary, V.C., Ballingeary & Inchigeela Historical Society, Retrieved 26 September 2008

- Batchelor & Matson, p. 4

- "No. 29376". The London Gazette (Supplement). 19 November 1915. p. 11574.

- "No. 29275". The London Gazette (Supplement). 24 August 1915. p. 8506.

- Batchelor & Matson, p. 5

-

- Holloway, Stanley; Richards, Dick (1967). Wiv a little bit o’ luck: The life story of Stanley Holloway. London: Frewin. ASIN B0000CNLM5. OCLC 3647363. page 60

- Stewart, Iain. "The Guards Regimental Headquarters". Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- macroom-online history: Michael O'Leary, V.C., Macroom Chamber of Commerce, Retrieved 26 September 2008

References

- Batchelor, Peter F. & Matson, Christopher (1997). VCs of the First World War - The Western Front 1915. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-1980-9.

- Kipling, Rudyard (1997) [1923]. "1915 La Bassée to Laventie". The Irish Guards in the Great War, Vol. 1. Spellmount Limited.

Further reading

- The Register of the Victoria Cross (1981, 1988 and 1997)

- Clarke, Brian D. H. (1986). "A register of awards to Irish-born officers and men". The Irish Sword. XVI (64): 185–287.

- Ireland's VCs ISBN 1-899243-00-3 (Dept of Economic Development, 1995)

- Monuments to Courage (David Harvey, 1999)

- Irish Winners of the Victoria Cross (Richard Doherty & David Truesdale, 2000)

External links

- Grave Location for holders of the Victoria Cross in North West London, www.victoriacross.org.uk, Retrieved 27 September 2008

- Michael John O'Leary at Find a Grave