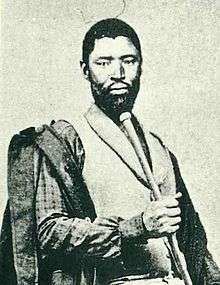

Mgolombane Sandile

Mgolombane Sandile (1820–1878) was a Chief of the Ngqika ("Gaikas") and Paramount-Chief of the Rharhabe tribe - a sub-group of the Xhosa nation. A dynamic and charismatic chief, he led the Xhosa armies in several of the Cape-Xhosa Frontier Wars.

Having recently been equipped with modern fire-arms, Sandile's forces successfully inflicted losses on their enemies that led to Sandile gaining a reputation as a Xhosa hero. He was captured during the War of the Axe in 1847, but on his release he was granted land in "British Kaffraria" for his people.

He later supported Sarhili (Kreli), Paramount-Chief of the Gcaleka, in a war against the Cape Colony and the Fingo tribe, and he was killed in 1878 in a shootout with Fingo soldiers.

Early life

He was born at Burnshill in 1820, at which time the Xhosa lands were still independent. His father Ngqika (after whom the entire Ngqika clan of Xhosa were named) died in 1829 while Sandile was still quite young and Maqoma, Sandile’s brother, acted as Regent until 1872 when Sandile was installed as King. Sandile was born with one leg shorter than the other, which made it difficult for him to walk, but he nevertheless played an important role in the Frontier Wars. The Xhosa nation had long been divided between the eastern Gcaleka (ruled at the time by Sarhili) and Sandile's Rharhabe to the west. However Sarhili, also known as "Kreli", had a role akin to paramount-king of all the Xhosa.

The Seventh Frontier War (1846-47)

The 7th Frontier War was also known as the "War of the Axe" or the "Amatola War".

Background to the war

Tension had been simmering between farmers and marauders, on both sides of the frontier, since the previous conflict. A severe drought forced desperate Xhosa to engage in cattle raids across the frontier in order to survive. In addition, land that had been captured in the previous war was scheduled by the government to be given back to the Xhosa. However there was great agitation via the Graham's Town Journal, of Eastern Cape settlers who wanted to annexe and settle this territory.

The event that actually ignited the war was a trivial dispute over a raid. A Khoikhoi escort was transporting a manacled Xhosa thief to Grahamstown to be tried for stealing an axe, when he was attacked and killed by Xhosa raiders. Sandile refused to surrender the murderer and war broke out in March 1846.

In addition to the regular British columns, the war involved several groups of mixed "Burgher forces", comprising mainly Khoi, Fengu and Boer Commandos, who were recruited locally to fight on the colonial side under their leader Andries Stockenstrom.

In the ensuing war, Sandile's Ngqika were assisted by portions of the Ndlambe,[1] and the Thembu. His forces outnumbered the colonials by over ten times, and had by this time replaced their traditional weapons with modern firearms. It was their new use of guns that made the Xhosa considerably more effective in fighting the British.[2]

Sandile's initial victories

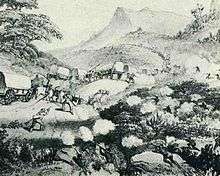

Sandile's forces won initial victories over the regular British forces. A slow British column, sent to confront Sandile, was temporarily delayed at the Amatola Mountains and Xhosa raiders were able to quickly capture the centre of the three-mile-long wagon train, which was not being defended - carrying away the British supplies.

Sandile then poured his forces across the border as the outnumbered British fell back, abandoning their outposts. The only successful resistance was from the local Mfengu people, who defended their villages from the far larger Xhosa forces. On 28 May, 8,000 of Sandile's men attacked the last remaining British garrison, at Fort Peddie, but fell back after a long shootout with British and Fingo troops. His army then marched on Grahamstown itself, but was held up when a sizeable army of Ndlambe Xhosa were defeated on 7 June 1846 by General Somerset on the Gwangu, a few miles from Fort Peddie. Both Xhosa and colonials were by now considerably hampered by drought.

Involvement of the Cape "Burgher" commandos

In desperation, the British called in Stockenstrom and the local Cape Burgher forces whose fast-moving commandos, with their considerable local knowledge, inflicted a string of defeats on Sandile's Ngqika.[3][4]

The commandos then rode deep into the Transkei Xhosa heartland, eventually riding right into the village of Gcaleka King Sarhili himself, the paramount chief of all the Xhosa, and negotiating with him an overall treaty, for peace with all Xhosa.

Later stages of the war

However, disagreements between these local Burghers and the regular British Imperial army caused Stockenstrom's commandos to withdraw from the war, leaving the British and the Xhosa - both starving and afflicted by fever - to a long, drawn-out war of attrition.

The effects of the drought were worsened through the use, by both sides, of scorched earth tactics. Gradually, as the armies weakened, the conflict subsided into waves of petty and bloody recriminations. At one point, violence flared up again after Ngqika tribesmen supposedly stole four goats from the neighbouring Kat River Settlement.

Sandile gained considerable respect for successfully eluding the British during their intensive sweeps of the Amatola forests, in spite of his physical disability. The war continued until Sandile was eventually captured during negotiations, and sent to Grahamstown. Though he was later released, the other Xhosa chiefs gradually laid down their arms. On 23 December 1847, the Keiskamma to upper Kei region was annexed as the British Kaffraria Colony, with King William's Town as capital.

The Eighth Frontier War (1850–53)

Also known as "Mlanjeni's War". Bitter at their recent defeat in the War of the Axe, the Xhosa found hope in a new prophet Mlanjeni, who predicted that the Xhosa would be unaffected by the colonists' bullets and promised supernatural aid to assist in the overthrow of their white neighbours.

Initial victories

Believing that the chiefs were responsible for the unrest caused by Mlanjeni's preaching, Governor Sir Harry Smith travelled to British Kaffraria to meet with the prominent chiefs. Sandile refused to attend a meeting outside Fort Cox, as he distrusted Governor Smith's motives, so Smith ordered him deposed and declared him a fugitive. On 24 December, a British detachment sent to arrest Sandile was ambushed by Xhosa warriors in the Boomah Pass. The party was forced to retreat to Fort White under heavy fire.

The Xhosa forces advanced into the colony and British Kaffraria erupted in a massive uprising in December 1850, joined by half-Khoi, half-Xhosa chief Hermanus Matroos, and by large numbers of the Kat River Khoikhoi. British military villages along the frontier were burned, and the post at Line Drift captured.[5]

Setbacks

After these initial successes, however, the Xhosa experienced a series of setbacks. Xhosa forces were repulsed in separate attacks on Fort White and Fort Hare. Similarly, on January 7, Hermanus and his supporters launched an offensive on the town of Fort Beaufort, which was defended by a small detachment of troops and local volunteers. The attack failed and Hermanus was killed.[6]

Involvement of the local Cape commandos

By the end of January, the imperial troops had received local reinforcements from the Cape Colony, and a force under Colonel Mackinnon was able to successfully drive north from King William's Town to re-supply the beleaguered garrisons at Fort White, Fort Cox and Fort Hare. They expelled the remainder of Hermanus' rebel forces (now under the command of Willem Uithaalder) from Fort Armstrong, and drove them west toward the Amatola Mountains.

Insurgents led by Sandile's brother Maqoma established themselves in the forested Water Kloof, and held out for a considerable time in this stronghold.

Aftermath and the Cattle-killing

The 8th frontier war was the most bitter and brutal in the series of Xhosa wars. It lasted over two years and ended in the complete subjugation of the Ciskei Xhosa.

Following the cessation of hostilities, the Xhosa, in desperation, turned to the millennialist movement (1856–1858) of the Prophetess Nongqawuse, which began in neighbouring Transkei 1856, and led them to destroy their own means of subsistence in the belief that it would bring about salvation by supernatural spirits. While the ensuing famine effected primarily the Gcaleka on the other side of the Kei, it also caused hardship among Sandile's people, and a wave of impoverished refugees.

After 1858 however, hostilities died down and peace returned to the frontier. The Cape Colony received representative and then responsible government and instituted the multi-racial Cape Qualified Franchise in an attempt to make its political system more inclusive. As expansionist pressure against the Xhosa also eased, and the Cape economy boomed in the early 1870s, the frontier saw over a decade of relative quiet.

The Ninth Frontier War (1877–79)

A series of devastating droughts across the Transkei began to place severe strain on the relative peace which had prevailed for the previous few decades. As the historian De Kiewiet memorably said: "In South Africa, the heat of drought easily becomes the fever of war ."[7] The droughts had begun as early as 1875 in Gcalekaland and had spread to other parts of the Transkei and Basutoland, and even into the Cape Colony controlled Ciskei. Their severity increased up until 1877 when they were the worst ever recorded, and ethnic tensions began to break out, particularly between the Mfengu, the Thembu and the Gcaleka Xhosa.[8][9][10]

This 9th War (also known as the Mfengu-Gcaleka War) started outside of the Cape's frontier in neighbouring Transkei, after the supposed harassing of the Mfengu/Fingo people, by Sarhili's Gcaleka Xhosa. An initial bar fight rapidly expanded into inter-tribal violence across the Cape frontier. The Cape Colony was swiftly pulled into the conflict as they were traditional allies of the Fengu, and the British Governor got involved with the intention of using the war as a pretext to annex the final independent Xhosa state, Gcalekaland. In the complex, multi-sided war that followed, the Gcaleka called upon Sandile to join the conflict by declaring war on the Cape Colony. Sandile, who on his previous release had been granted land in "British Kaffraria" for his people, was initially uncertain about going to war. His Councillors and Chiefs all advised him not to, but his younger generation of warriors were persuaded by the Gcaleka appeal. Eventually, he fatally threw in his lot with Sarhili and his Gcaleka armies. The armies of the Fingo and the Cape Colony soon emerged victorious, Sandile was killed in a shootout with Fingo soldiers in 1878, and all remaining Xhosa territory then became part of the Cape Colony.[11]

Death

On 29 May 1878, Sandile was mortally wounded in a shoot-out with a detachment of Fengu troops (the Fengu were a Xhosa-speaking nation who had long suffered oppression at the hands of the Gcaleka Xhosa, and had consequently become traditional allies of the Cape Colony). He died a few days later and his body was brought to a nearby military camp. Widely admired by this time, he was given a full military funeral at which his body was carried on eight rifles by Fingo pall-bearers. Sandile was buried by the graves of British soldiers A. Dicks and F. Hillier, who were killed in the same war.[12]

Sandile's grave is today about 16 kilometres from Stutterheim at the foothills of the Amatola Mountains where he fought many of his campaigns. A memorial plaque erected at the grave site in 1941 reads as follows:

SANDILE

Chief of the Gaikas. Born about 1820

Killed in the Ninth Kaffir War 1877/1878

and buried here on 9.6.1878

Recent excavations - overseen by the local Xhosa community - have confirmed the body's identity and dispelled centuries-old rumours that Sandile was posthumously decapitated.

He was survived by his daughter, Emma Sandile, who later became a landowner in the Cape Colony.[13]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mgolombane Sandile. |

References

- Cana 1911, p. 239.

- "Conquest of the Eastern Cape 1779-1878" Archived 2012-05-03 at the Wayback Machine, South African History Online.

- "Fort Peddie". Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- "General South African History Timeline: 1800s" Archived 2019-04-21 at the Wayback Machine, South African History Online.

- Abbink, J; Jeffrey B. Peires (1989). The Dead Will Arise: Nongqawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle-Killing. LULE. ISBN 9780253205247.

- Abbink, J; Mirjam de Bruijn; Klaas van Walraven (2008). Rethinking Resistance: Revolt and Violence in African History. LULE. ISBN 978-9004126244. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- Kiewiet, Cornelis W. de (1941), A History of South Africa, Social and Economic., Oxford, England: Clarendon Press. p.105

- J. Fage, R. Oliver: The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 6 (1870-1905). Cambridge University Press, 1985. p.387.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-12. Retrieved 2013-03-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- C. Bundy: The Rise and Fall of South African Peasantry. University of California Press, 1979. p.83.

- "Xhosa Wars". Reader's Digest Family Encyclopedia of World History. The Reader's Digest Association. 1996.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-11. Retrieved 2010-08-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Daymond, Margaret J. (2003). Women Writing Africa: The Southern Region. New York: New York Feminist Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-155861-407-9.