Messier 95

Messier 95, also known as M95 or NGC 3351, is a barred spiral galaxy located about 33 million light-years away in the zodiac constellation Leo. It was discovered by Pierre Méchain in 1781, and catalogued by fellow French astronomer Charles Messier four days later. On 16 March 2012, a supernova was discovered in M95.

| Messier 95 | |

|---|---|

M95. Credit: NASA | |

| Observation data (J2000 epoch) | |

| Constellation | Leo |

| Right ascension | 10h 43m 57.7s[1] |

| Declination | +11° 42′ 14″[1] |

| Redshift | 778 ± 4 km/s[1] |

| Distance | 32.6 ± 1.4 Mly (10.0 ± 0.4 Mpc)[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 11.4[1] |

| Characteristics | |

| Type | SB(r)b[1] |

| Apparent size (V) | 3′.1 × 2′.9[1] |

| Other designations | |

| NGC 3351,[1] UGC 5850,[1] PGC 32007[1] | |

The galaxy has a morphological classification of SB(r)b,[1] with the SBb notation indicating it is a barred spiral with arms that are intermediate on the scale from tightly to loosely wound, and an "(r)" meaning an inner ring surrounds the bar.[3] The latter is a ring-shaped, circumnuclear star-forming region with a diameter of approximately 2,000 light-years (610 pc).[4] The spiral structure extends outward from the ring.[3]

The ring structure of M95 has a mass of 3.5×108 M☉ in molecular gas and a star formation rate of 0.38 M☉ yr−1. The star formation is occurring in at least five regions with diameters between 100 and 150 pc that are composed of several star clusters ranging in size from 1.7 to 4.9 pc. These individual clusters contain (1.8–8.7)×106 M☉ of stars, and may be on the path to forming globular clusters.[5]

A Type II supernova, designated as SN 2012aw, was discovered in M95 on 16 March 2012.[6][7][8] The light curve of the supernova displayed a significant flattening after 27 days, thus classifying it as a Type II-P, or "plateau", core-collapse supernova.[9] The disappearance of the progenitor star was later confirmed from near-infrared imaging of the region. The brightness of the presumed red supergiant progenitor allowed its mass to be estimated as 12.5±1.5 M☉.[10]

M95 is one of several galaxies within the M96 Group, a group of galaxies in the constellation Leo. The group also includes the Messier objects M96 and M105.[11][12][13][14]

Gallery

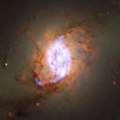

Messier 95 shows the process of redistributing energy into the interstellar medium within star-forming galaxies.[15]

Messier 95 shows the process of redistributing energy into the interstellar medium within star-forming galaxies.[15] Hubble Space Telescope image of Messier 95.[16]

Hubble Space Telescope image of Messier 95.[16]

References

- "NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database". Results for NGC 3351. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- Jensen, Joseph B.; Tonry, John L.; Barris, Brian J.; Thompson, Rodger I.; et al. (2003). "Measuring Distances and Probing the Unresolved Stellar Populations of Galaxies Using Infrared Surface Brightness Fluctuations". Astrophysical Journal. 583 (2): 712–726. arXiv:astro-ph/0210129. Bibcode:2003ApJ...583..712J. doi:10.1086/345430.

- Buta, Ronald J.; et al. (2007), Atlas of Galaxies, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1−25, ISBN 978-0521820486.

- Colina, L.; Garcia Vargas, M. L.; Mas-Hesse, J. M.; Alberdi, A.; Krabbe, A. (1997). "Nuclear Star-forming Structures and the Starburst–Active Galactic Nucleus Connection in Barred Spirals NGC 3351 and NGC 4303". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 484 (1): L41–L45. Bibcode:1997ApJ...484L..41C. doi:10.1086/310766.

- Hägele, Guillermo F.; et al. (June 2007), "Kinematics of gas and stars in the circumnuclear star-forming ring of NGC3351", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 378 (1): 163−178, arXiv:astro-ph/0703140, Bibcode:2007MNRAS.378..163H, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.11751.x

- "Deep Sky Videos". Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- "Supernova 2012aw: the pictures!". Retrieved 19 March 2012.

- "List of Recent Supernovae". Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- Bayless, Amanda J.; et al. (February 2013), "The Long-lived UV "Plateau" of SN 2012aw", The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 764 (1): 6, arXiv:1210.5496, Bibcode:2013ApJ...764L..13B, doi:10.1088/2041-8205/764/1/L13, L13.

- Fraser, Morgan (February 2016), "The disappearance of the progenitor of SN 2012aw in late-time imaging", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters, 456 (1): L16−L19, arXiv:1507.06579, Bibcode:2016MNRAS.456L..16F, doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slv168.

- Tully, R. B. (1988). Nearby Galaxies Catalog. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-35299-4.

- Fouque, P.; Gourgoulhon, E.; Chamaraux, P.; Paturel, G. (1992). "Groups of galaxies within 80 Mpc. II – The catalogue of groups and group members". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement. 93: 211–233. Bibcode:1992A&AS...93..211F.

- Garcia, A. (1993). "General study of group membership. II – Determination of nearby groups". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement. 100: 47–90. Bibcode:1993A&AS..100...47G.

- Giuricin, G.; et al. (2000). "Nearby Optical Galaxies: Selection of the Sample and Identification of Groups". Astrophysical Journal. 543 (1): 178–194. arXiv:astro-ph/0001140. Bibcode:2000ApJ...543..178G. doi:10.1086/317070.

- "Caught in the act". www.eso.org. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Rings upon rings". www.spacetelescope.org. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Messier 95. |

- Messier 95 on WikiSky: DSS2, SDSS, GALEX, IRAS, Hydrogen α, X-Ray, Astrophoto, Sky Map, Articles and images

- SEDS: Spiral Galaxy M95

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Barred Spiral Galaxy M95 (14 March 2007)

- Merrifield, Michael. "Supernova in M95 – SN 2012aw and its progenitor". Deep Sky Videos. Brady Haran.