Meridian City Hall

City Hall in Meridian, Mississippi in the United States is located at 601 24th Avenue. Originally designed by architect P.J. Krouse in 1915, the building underwent several renovations during the 1950s that diminished the historic quality of the building. City Hall was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979 and as a Mississippi Landmark in 1988. After complaints of a faulty HVAC system, the building underwent a restoration to its original 1915 appearance beginning in September 2006. The project was originally estimated to cost $7–8 million and last two years. Because of several factors including the building's listings on historic registers, a lawsuit filed by a subcontractor, and unforeseen structural problems, the final cost and duration of the renovation far exceeded original estimates. The renovation was completed in January 2012 at a total cost projected to reach around $25 million after interest on debt.

Municipal Building | |

Mississippi Landmark

| |

.jpg) City Hall after restoration, in 2018 | |

| |

| Location | 601 24th Ave, Meridian, Mississippi |

|---|---|

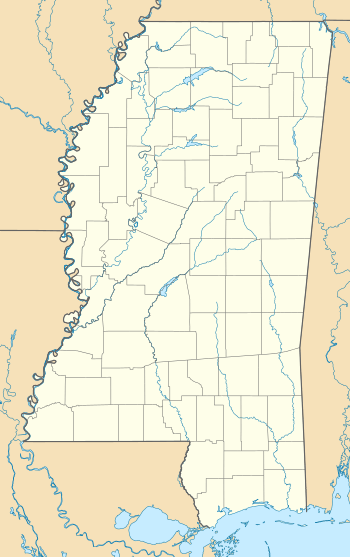

| Coordinates | 32°21′49″N 88°42′8″W |

| Area | 1 acre (0.40 ha) |

| Built | 1915 |

| Built by | Hancock & McArthur |

| Architect | P.J. Krouse |

| Architectural style | Beaux Arts |

| Restored | 2006–2012 |

| MPS | Meridian MRA |

| NRHP reference No. | 79003399[1] |

| USMS No. | 075-MER-0150-NR-ML |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 18, 1979 |

| Designated USMS | May 6, 1988[2] |

The building is home to many city offices, including that of Percy Bland, the current mayor of Meridian.

History

Before the current city hall was built in 1915, the city government operated out of a building built in 1885 and designed by Gustav Torgenson,[3] the same architect that designed the Riley Center in 1889.[4] Architects R.H. Hunt, C.L. Hutchisson, and P.J. Krouse competed for the chance to design the new city hall in March 1914. Krouse was chosen to design the building on April 15, 1914,[3] and Hutchisson was named the consulting architect. C.O. Craft is listed as the superintendent of the building, C.H. Miller as the superintendent for the architect, and Hancock & MacArthur are listed as contractors.[5]

The building was originally built in the Beaux Arts style. There were no major alterations to the building until the 1950s, when modern conveniences were added. Air conditioning was added to the building, necessitating drop ceilings to make room for the ducts, which obscured the original plaster moulding in the interior. Wood panelling was added to create more offices out of the large chambers present in the original design, and mahogany windows were replaced with aluminum ones.[6] Windows on the ground floor were filled with concrete during the 1950s as well.[7] City governments, believing they were making improvements to the building, actually harmed it or diminished its historical value. Terracotta tiles were painted over, which trapped moisture inside the tiles and caused parts of the building to rot. Scagliola columns were painted blue, wood and marble floors were covered with linoleum, and the grand staircase was replaced with an elevator.[8]

The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979[1] and as a Mississippi Landmark in 1988.[2]

Restoration

By 2003, some city workers had complained about faulty HVAC systems in the building. The city then hired consultants to repair the systems, but they found so many other problems with the building that the city decided to renovate the entire building.[9] The city began planning the operation in 2005, and the first bonds to finance the renovation were sold in 2006. The renovation was split up into four phases: planning, selective demolition, exterior renovation, and interior renovation. The first phase took place in 2005 before construction began. Phase II began in 2006, Phase III began in 2007, and Phase IV began in 2009.[6] During the renovation, temporary City Hall was located at 2412 7th Street.[10]

During Phase III, the terracotta tiles on the exterior were methodically replaced, cross and jack sunscreens were returned to their original black shade, and the fountain constructed on the front lawn in the 1950s was replaced.[8] Thirty-two of the decorative column capitals were replaced, and a new parapet cap and flashing system was designed for the roof.[11] The renovation was awarded the Masonry Construction Online Project of the Year Award for 2009.[11]

By March 2010, two of three fire stairs had been installed, and the elevator shaft had been moved to make way for a marble staircase.[6] By January 2011, the building's scagliola columns had been restored, the decorative glazing on the floors had been finished, and progress was being made on the installation of the elevators.[12] In September 2011, most electrical and mechanical systems had been installed, and only minor details on the inside of the building were missing. Several handrails and a few panes of glass had not yet been installed, as well as minor details such as paint and finish. Exterior landscaping was farther behind, partially because it was not part of the original plan laid out by former mayor John Robert Smith.[13]

An open house was held on January 31, 2012, after the building was completed,[14] and the first post-restoration meeting of the city council was held on February 21.[15]

Cost and Funding

The original estimate of the cost was $7–8 million, which would be paid for by a single general obligation bond of $10 million that was also supposed to fund the construction of a new fire station and several smaller projects. By 2010, that estimate had more than doubled to $17 million. One reason for the increase was unforeseen necessary repairs, such as iron supports that had rusted to less than half their original size and a damaged drainage system. The building's listing on the National Register of Historic Places also increased cost. The Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH) required that anything salvageable from the original building must be repaired and reused rather than replaced. The terracotta tiles on the outside of the building, if not salvaged, were required to be replaced with exact replicas, and only two companies in the world could make them.[6] In some cases, MDAH forced the city to spend more than they planned for historical accuracy. For example, the city had originally planned to install relatively cheap windows painted to look like the 1915 originals, but MDAH required the city to buy more expensive mahogany.[9]

By September 2011, the cost of the renovation was tagged at $17,224,230. The eventual cost of the renovation is projected to approach $25.2 million, with $8 million paid in interest and fees on debt. Cost breakdown is as follows:[13]

- $8,542,000 for interior renovation and landscaping

- $6,462,253 for exterior renovation

- $1,234,244 (as of September 2011) for design

- $544,075 for selective demolition

- $300,000 for interior furnishings

- $126,102 (as of September 2011) for a historic finishes consultant

- $15,556 other

Each phase of construction is financed individually, but the original $10 million bond in 2006 was enough to cover the first three phases of construction.[9] For Phase IV, the city received a block grant from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act totaling $182,400 for the installation of energy efficient equipment in the building.[9][16] A second $10 million bond was acquired to pay for the remaining costs.[13]

Delays

The unforeseen structural problems and the strictness of MDAH not only increased the cost of the project, but they also continued to push back the estimated date of completion. When the renovation began in 2006, it was expected to take only two years. Phase III took longer than expected because of the historical standards imposed by MDAH. Since only two companies in the world could make the terracotta tiles for the exterior of the building, there was a long wait for them.[6] On top of that, it also took a long time to place them on the walls because they each had a specific place and none were standardized.[6] Though Phase III began in 2007, the installation of the tiles didn't begin until January 2009.[17] By February, 400 of the 1,643 tiles had been replaced.[18] Because of this wait, the completion date was moved back to Spring 2010.[17] By March 2010, the scheduled completion date was February 2011.[19]

Another hiccup in the renovation process was a lawsuit filed by EverGreene Architectural Arts, one of the project's subcontractors, against Panola Construction, the general contractor, and B.B. Archer, the architect. Evergreene claimed that negligent and incompetent actions had led to cost increases and scheduling delays for both Evergreene and the city.[20] Archer characterized Evergreene's work as "shoddy" and "falling apart."[12] Evergreene, who was in charge of producing a decorative plaster for the building's interior, was later fired, causing further delays as the contractor searched for a replacement.[21] As a result of this controversy, the scheduled completion date was pushed back to May 23, 2011.[12] As that deadline approached, the deadline was pushed back to September 1, 2011. Cheri Barry, the city's mayor, said that the building renovations and furnishings would be complete by that time so that the building could be occupied again, but the landscaping would not yet be complete. Landscaping was scheduled to begin sometime between fall 2011 and spring 2012.[22] As the September deadline approached, Mayor Barry stopped issuing new deadlines, and city officials began referring to the building as being "close to completion."[13]

After restoration

The restoration was completed in January 2012, and Cheri Barry announced the holding of an open house for the building on January 31.[23][24] The open house included guest speakers such as former mayor Jimmy Kemp, state commissioner Dick Hall, and several members of the design team.[14] Attendees were given a historical tour of the building, and a reception was held in the third floor ballroom with music, art, and refreshments.[23]

The completed building matches the original architectural drawings as much as possible while still conforming to modern building codes. The panelling used to create small offices was removed, and the rooms are in the same places they were in 1915.[6] All vinyl and plastic were removed from the interior and replaced with historic materials like wood, marble, plaster, and glass. A set of fire stairs on all three floors was added, and the elevator was moved to a different location to make way for a restored grand staircase of marble.[8] Other interior changes include replacing the aluminum windows added in the 1950s with mahogany replicas of the originals, removing vinyl flooring to expose the original oak and marble beneath, and replacing aluminum doors and unsightly fluorescent lights.[7]

The renovated building is also more energy efficient. Automatic lighting controls, insulated glass, efficient HVAC systems, and shades that automatically lower to keep out sunlight at specific times of day were added.[7] The HVAC system is housed in a mechanical building across the street.[6]

The first floor of the building houses the Human Resources department, the Information Technology department, and a conference room.[8] The second floor is the main entrance of the building and is home to the mayor's office and the Finance and Records department as well as the Public Works department.[8][25] The third floor originally housed an auditorium with a large stage and the Community Development department. The auditorium was rebuilt, though smaller in size than the original, and serves as a public space available to be rented for receptions and as the city council chambers.[8][25] A kitchen for event catering was constructed beside the auditorium, and the floor also contains office space and a conference room.[8]

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "Mississippi Landmarks" (PDF). Mississippi Department of Archives and History. May 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-10-09. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- W. White (May 27, 2010). "An Alabama–Mississippi Architectural Partnership". Preservation in Mississippi. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- "Grand Opera House Project". City of Meridian. Archived from the original on 2010-02-09. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- Jody Cook (February 1979). "State of Mississippi Historic Sites Survey: Municipal Building". National Park Service. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jennifer Jacob Brown (March 21, 2010). "City Hall Renovations: The Making of a Modern Relic". The Meridian Star. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- Jennifer Jacob (June 18, 2008). "Council Updated on City Hall". The Meridian Star. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- Jennifer Jacob (June 24, 2008). "Rebuilding a Legacy: Inside the Renovation of City Hall". The Meridian Star. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- Jennifer Jacob Brown (March 7, 2009). "The Costs and Complications of City Hall Reconstruction". Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- "City Hall Relocation". Official website of Meridian, MeridianMS.org. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

- "Projects of the Year". Masonry Construction Online. 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-12-20. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- Jennifer Jacob Brown (January 19, 2011). "New 'drop dead' date for City Hall reopening". The Meridian Star. Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- Jennifer Jacob Brown (September 18, 2011). "Taj Ma-City Hall – Renovations: Where are we now?". The Meridian Star. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- Ida Brown (February 1, 2012). "Doors of newly renovated city hall opened to the public". The Meridian Star. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- Jennifer Jacob Brown (February 22, 2012). "New City Hall in full operation: City council holds first meeting in new chambers". The Meridian Star. Retrieved 2012-02-22.

- "Recipient Project Summary". Recovery.gov. September 18, 2009. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- "New Progress on City Hall". The Meridian Star. January 7, 2009. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- Jennifer Jacob Brown (February 18, 2009). "City Hall Update". The Meridian Star. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- Jennifer Jacob Brown (March 17, 2010). "Last Phase of City Hall Renovations on Schedule". The Meridian Star. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- Jennifer Jacob Brown (September 12, 2010). "City Hall renovations on schedule, but tricky work sparks lawsuit". The Meridian Star. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- Jennifer Jacob Brown (November 3, 2010). "City Hall renovations could be delayed". The Meridian Star. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- Jennifer Jacob Brown (May 18, 2011). "City Hall project delayed again". The Meridian Star. Retrieved 2011-05-27.

- Jennifer Jacob Brown (January 18, 2012). "City Hall dedication set for January 31". The Meridian Star. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- Chip Scarborough (January 31, 2012). "Public Gets First Look at Renovated City Hall". WTOK-TV. Retrieved 2012-01-31.

- Wade Phillips (February 16, 2012). "City Hall Gets Back to Business". WTOK-TV. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Meridian City Hall. |