Meluhha

Meluḫḫa or Melukhkha (Me-luḫ-ḫaKI 𒈨𒈛𒄩𒆠) is the Sumerian name of a prominent trading partner of Sumer during the Middle Bronze Age. Its identification remains an open question, but most scholars associate it with the Indus Valley Civilization.[4]

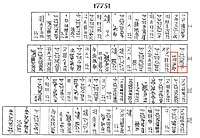

𒈨𒈛𒄩𒆠

Etymology

Asko Parpola identifies Proto-Dravidians with the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) and the Meluhha people mentioned in Sumerian records. According to him, the word "Meluhha" derives from the Dravidian words mel-akam ("highland country"). It is possible that the IVC people exported sesame oil to Mesopotamia, where it was known as ilu in Sumerian and eḷḷu in Akkadian. One theory is that these words derive from the Dravidian name for sesame (eḷḷ or eḷḷu). However, Michael Witzel, who associates IVC with the ancestors of Munda speakers, suggests an alternative etymology from the para-Munda word for wild sesame: jar-tila. Munda is an Austroasiatic language, and forms a substratum (including loanwords) in Dravidian languages.[5]

Asko Parpola relates Meluhha with Mleccha who were considered non-Vedic "barbarian" in Vedic Sanskrit.[6][7]

Trade with Sumer

_Magan_Meluha_with_transcription.jpg)

Sumerian texts repeatedly refer to three important centers with which they traded: Magan, Dilmun, and Meluhha.[12][13] Magan is usually identified with Egypt in later Assyrian texts; but the Sumerian localization of Magan was probably Oman. Dilmun was a Persian Gulf civilization which traded with Mesopotamian civilizations, the current scholarly consensus is that Dilmun encompassed Bahrain, Failaka Island and the adjacent coast of Eastern Arabia in the Persian Gulf.[14][15]

Inscriptions

In an inscription, Sargon of Akkad (2334-2279 BCE) referred to ships coming from Meluhha, Magan and Dilmun.[16] His grandson Naram-Sin (2254-2218 BCE) listing the rebel kings to his rule, mentioned "(..)ibra, man of Melukha".[16] In an inscription, Gudea of Lagash (21st century BCE) referred to the Meluhhans who came to Sumer to sell gold dust, carnelian etc...[16][13] In the Gudea cylinders (inscription of cylinder A, IX:19), Gudea mentions that "I will spread in the world respect for my Temple, under my name the whole universe will gather in it, and Magan and Meluhha will come down from their mountains to attend".[17] In cylinder B, XIV, he mentions his procurement of "blocks of lapis lazuli and bright carnelian from Meluhha."[13][18] There are no known mentions of Meluhha after 1760 BCE.[16]

Meluhha is also mentioned in mythological legends such as "Enki and Ninhursaga":

"May the foreign land of Meluhha load precious desirable cornelian, perfect mes wood and beautiful aba wood into large ships for you"

— Enki and Ninhursaga[19]

Artifacts

There is extensive presence of Harappan seals and cubical weight measures in Mesopotamian urban sites. Specific items of high volume trade are timber and specialty wood such as ebony, for which large ships were used. Luxury items also appear, such as lapis lazuli mined at a Harappan colony at Shortugai (modern Badakhshan in northern Afghanistan), which was transported to Lothal, a port city in Gujarat in western India, and shipped from there to Oman, Bahrain and Sumer.

In the 1980s, important archaeological discoveries were made at Ras al-Jinz (Oman), located at the easternmost point of the Arabian Peninsula, demonstrating maritime Indus Valley connections with Oman, and the Middle East in general.[20][21]

"Meluhha dog"

In one of his inscriptions, Ibbi-Sin mentions that he received as a booty from Marḫaši a Meluhha red dog:[23][24]

"Ibbi-Sîn, the god of his country, the mighty king, king of Ur and king of the four world quarters, his speckled Meluḫḫa 'dog', from Marḫaši brought by them as tribute, a replica of it he fashioned, and for his life he dedicated it to him (Nanna)."

— Meluhha dog inscription of Inni-Sin.[25]

The qualifier used to describe the dog is 𒁱, which can be read either dar "red" as an adjective,[26] or gun3 "speckled" as an intransitive verb,[27] and interpretations vary based on these two possible meanings.[28]

It is thought that this "red dog" could be a dhole, also called "Asiatic red dog", a type of red-colored dog native to southern and eastern Asia.[22]

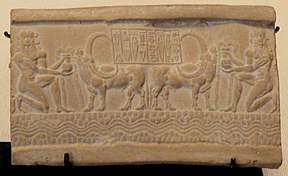

Animal figurines

Various figurines of exotic animals in gold or carnelian are thought to have been imported from Meluhha. Many such statuettes have been found in Mesopotamian excavations.[22] The carnelian statuette of an Asian monkey was found in the excavation of the Acropolis of Susa, and dated to circa 2340 - 2100 BCE. It is thought that it may have been imported from Indus Valley. It is now in the Louvre Museum, reference Sb5884.[29]

Meluhhan trading colony in Sumer

Towards the end of the Sumerian period, there are numerous mentions in inscriptions of a Meluhha settlement in southern Sumer near the city-state of Girsu.[30] Most of the references seem to date to the Akkadian Empire and especially the Ur III period.[30] The location of the settlement has been tentatively identified with the city of Guabba.[30] The references to "large boats" in Guabba suggests that it may have functionned as a trading colony which initially had direct contact with Meluhha.[30]

It seems that direct trade with Meluhha subsided during the Ur III period, and was replaced by trade with Dilmun, possibly corresponding to the end of urban systems in the Indus Valley around that time.[30]

.jpg)

Transcription of tablet BM 17751, with the word "Meluhha" (𒈨𒈛𒄩𒆠).[31] Column II continues Column I on the reverse.

Transcription of tablet BM 17751, with the word "Meluhha" (𒈨𒈛𒄩𒆠).[31] Column II continues Column I on the reverse.

Conflict with the Akkadians and Neo-Sumerians

.jpg)

According to some accounts of the Akkadian Empire ruler Rimush, he fought against the troops of Meluhha, in the area of Elam:[35]

"Rimuš, the king of the world, in battle over Abalgamash, king of Parahshum, was victorious. And Zahara[38] and Elam and Gupin and Meluḫḫa within Paraḫšum assembled for battle, but he (Rimush) was victorious and struck down 16,212 men and took 4,216 captives. Further, he captured Ehmahsini, King of Elam, and all the nobles of Elam. Further he captured Sidaga'u the general of Paraḫšum and Sargapi, general of Zahara, in between the cities of Awan and Susa, by the "Middle River". Further a burial mound at the site of the town he heaped up over them. Furthermore, the foundations of Paraḫšum from the country of Elam he tore out, and so Rimuš, king of the world, rules Elam, (as) the god Enlil had shown..."

Gudea too, in one of his inscriptions, mentioned his victory over the territories of Magan, Meluhha, Elam and Amurru.[16]

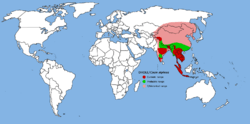

Identification with the Indus Valley

Most scholars suggest that Meluhha was the Sumerian name for the Indus Valley Civilization.[40] Finnish scholars Asko and Simo Parpola identify Meluhha (earlier variant Me-lah-ha) from earlier Sumerian documents with Dravidian mel akam "high abode" or "high country". Many items of trade such as wood, minerals, and gemstones were indeed extracted from the hilly regions near the Indus settlements. They further claim that Meluhha is the origin of the Sanskrit mleccha, meaning "barbarian, foreigner".[41]

.jpg)

Early texts (c. 2200 BC) seem to indicate that Meluhha is to the east, suggesting either the Indus valley or India. However, much later texts documenting the exploits of King Assurbanipal of Assyria (668–627 BC), long after the Indus Valley civilization had ceased to exist, seem to imply that Meluhha is to be found either in Africa, somewhere near Egypt.[43]

There is sufficient archaeological evidence for the trade between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley. Impressions of clay seals from the Indus Valley city of Harappa were evidently used to seal bundles of merchandise, as clay seal impressions with cord or sack marks on the reverse side testify. A number of these Indus seals have been found at Ur and other Mesopotamian sites.[44][45]

The Persian-Gulf style of circular stamped rather than rolled seals, also known from Dilmun, that appear at Lothal in Gujarat, India, and Failaka Island (Kuwait), as well as in Mesopotamia, are convincing corroboration of the long-distance sea trade network, which G.L. Possehl has called a "Middle Asian Interaction Sphere".[46] What the commerce consisted of is less sure: timber and precious woods, ivory, lapis lazuli, gold, and luxury goods such as carnelian and glazed stone beads, pearls from the Persian Gulf, and shell and bone inlays, were among the goods sent to Mesopotamia in exchange for silver, tin, woolen textiles, perhaps oil and grains and other foods. Copper ingots, certainly, bitumen, which occurred naturally in Mesopotamia, may have been exchanged for cotton textiles and chickens, major products of the Indus region that are not native to Mesopotamia—all these have been instanced.

Later era

In the Assyrian and Hellenistic eras, cuneiform texts continued to use (or revive) old place names, giving a perhaps artificial sense of continuity between contemporary events and events of the distant past.[48] For example, Media is referred to as "the land of the Gutians",[49] a people who had been prominent around 2000 BC.

Meluhha also appears in these texts, in contexts suggesting that "Meluhha" and "Magan" were kingdoms adjacent to Egypt. Assurbanipal writes about his first march against Egypt, "In my first campaign I marched against Magan, Meluhha, and Taharqa, king of Egypt and Ethiopia, whom Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, the father who begot me, had defeated, and whose land he brought under his sway."[50] In this context, "Magan" has been interpreted as "Muṣur" (ancient name of Egypt) and "Meluhha" as "Meroe" (capital of Nubia).[51]

In the Hellenistic period, the term is sometimes used to refer to Ptolemaic Egypt, as in its account of a festival celebrating the conclusion of the Sixth Syrian War.[52]

These references do not necessarily mean that early references to Meluhha also referred to Egypt. Direct contacts between Sumer and the Indus Valley had ceased even during the Mature Harappan phase when Oman and Bahrain (Magan and Dilmun) became intermediaries. After the sack of Ur by the Elamites and subsequent invasions in Sumer, its trade and contacts shifted west and Meluhha passed almost into mythological memory. The resurfacing of the name could simply reflect cultural memory of a rich and distant land, its use in records of Achaemenid and Seleucid military expeditions serving to aggrandize those kings.

See also

References

- "Cylinder Seal of Ibni-Sharrum". Louvre Museum.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- Brown, Brian A.; Feldman, Marian H. (2013). Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Walter de Gruyter. p. 187. ISBN 9781614510352.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- McIntosh 2008, p. 354.

- Parpola, Asko; Parpola, Simo (1975), "On the relationship of the Sumerian toponym Meluhha and Sanskrit mleccha", Studia Orientalia, 46: 205–238

- Witzel, Michael (1999), "Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Ṛgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic)" (PDF), Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies, 5 (1), p. 25, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-06, retrieved 2018-12-11

- Parpola, Asko (2015). The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 353. ISBN 9780190226930.

- "Meluhha interpreter seal. Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- "I will spread in the world respect for my Temple, under my name the whole universe will gather in it, and Magan and Meluhha will come down from their mountains to attend" "J'étendrai sur le monde le respect de mon temple, sous mon nom l'univers depuis l'horizon s'y rassemblera, et [même les pays lointains] Magan et Meluhha, sortant de leurs montagnes, y descendront" (cylinder A, IX:19)" in "Louvre Museum".

- "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk.

- Moorey, Peter Roger Stuart (1999). Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence. Eisenbrauns. p. 352. ISBN 978-1-57506-042-2.

- Moorey, Peter Roger Stuart (1999). Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence. Eisenbrauns. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-57506-042-2.

- Nayeem, M. A. (1990). Prehistory and Protohistory of the Arabian Peninsula: Bahrain. M. A. Nayeem. p. 32. ISBN 9788185492025.

- "Sa'ad and Sae'ed Area in Failaka Island". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- "MS 2814 - The Schoyen Collection". www.schoyencollection.com.

- "J'étendrai sur le monde le respect de mon temple, sous mon nom l'univers depuis l'horizon s'y rassemblera, et [même les pays lointains] Magan et Meluhha, sortant de leurs montagnes, y descendront" (cylinder A, IX:19)" in "Louvre Museum".

- Moorey, Peter Roger Stuart (1999). Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence. Eisenbrauns. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-57506-042-2.

- Michalowski, Piotr (2011). The correspondance of the Kings of Ur (PDF). p. 257, note 28.

- Maurizio Tosi: Die Indus-Zivilisation jenseits des indischen Subkontinents, in: Vergessene Städte am Indus, Mainz am Rhein 1987, ISBN 3805309570, S. 132-133

- Story of Ras Al Jinz. Archived 2016-09-10 at the Wayback Machine Oman Information

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- Gelb, I. J. (1970). "Makkan and Meluḫḫa in Early Mesopotamian Sources". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'Archéologie Orientale. 64 (1): 4. JSTOR 23294921.

- Kohl, Philip L. (2015). The Bronze Age Civilization of Central Asia: Recent Soviet Discoveries. Routledge. p. 389. ISBN 978-1-317-28225-9.

- "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- "Sumerian Dictionary "Dar" entry". oracc.iaas.upenn.edu.

- "Sumerian Dictionary "Gunu" entry". oracc.iaas.upenn.edu.

- Lawler, Andrew (2016). Why Did the Chicken Cross the World?: The Epic Saga of the Bird that Powers Civilization. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-2990-9.

- "Asian monkey statuette from Susa".

- Vermaak, Fanie (2008). "Guabba, the Meluhhan village in Mesopotamia". Journal for Semitics. 17/2: 454–471.

- Simo Parpola, Asko Parpola and Robert H. Brunswig, Jr "The Meluḫḫa Village: Evidence of Acculturation of Harappan Traders in Late Third Millennium Mesopotamia?" in Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient Vol. 20, No. 2, 1977, p. 136-137

- "Collections Online British Museum". www.britishmuseum.org.

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Frayne, Douglas. Sargonic and Gutian Periods. pp. 55–56.

- Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. Routledge. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Frayne, Douglas. Sargonic and Gutian Periods. pp. 57–58.

- Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: From the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. Taylor & Francis. p. 784. ISBN 978-0-415-39485-7.

- "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2002), The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective, Rowman Altamira, p. 219, ISBN 978-0-7591-0172-2

- Parpola, Asko; Parpola, Simo (1975). "On the relationship of the Sumerian Toponym Meluhha and Sanskrit Mleccha". Studia Orientalia. 46: 205–238.

- British Museum notice: "Gold and carnelians beads. The two beads etched with patterns in white were probably imported from the Indus Valley. They were made by a technique developed by the Harappan civilization" Photograph of the necklace in question

- Hansman, John (1973). "A "Periplus" of Magan and Meluhha". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 36 (3): 554–587. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00119858.

- "urseals". hindunet.org. Archived from the original on 2000-12-11.

- John Keay (2000). India: A History. p. 16.

- Possehl, G.L. (2007), “The Middle Asian Interaction Sphere”, Expedition 49/1

- Mathew, K. S. (2017). Shipbuilding, Navigation and the Portuguese in Pre-modern India. Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-351-58833-1.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc (1997). The Ancient Mesopotamian City. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 44.

- Sachs & Hunger (1988). Astronomical Diaries & Related Texts from Babylonia, vol.1. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. –330 Obv.18.

- Pritchard, James B. (2016). Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament with Supplement. Princeton University Press. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-4008-8276-2.

- History of Assurbanipall, Translated from the Cuneiform Inscriptions by George Smith. Williams and Norgate. 1871. pp. 15 and 48.

- Sachs & Hunger (1988). Astronomical Diaries & Related Texts from Babylonia, vol.2. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. –168 A Obv.14–15.

Bibliography

- McIntosh, Jane R. (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley : New Perspectives. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576079072.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Julian Reade (ed.) The Indian Ocean in Antiquity. London: Kegan Paul Intl. 1996

External links

- Meluhha and Agastya : Alpha and Omega of the Indus Script by Iravatham Mahadevan

_cropped.jpg)

.jpg)