First Dynasty of Ur

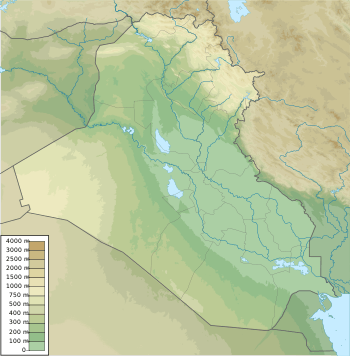

The First Dynasty of Ur was a 26th century-25th century BCE dynasty of rulers of the city of Ur in ancient Sumer.[1] It is part of the Early Dynastic period III of the History of Mesopotamia. It was preceded by the earlier First dynasty of Kish and First Dynasty of Uruk.[2]

(26th-25th century BCE)

Rule

According to the Sumerian King List, the final ruler of the First Dynasty of Uruk Lugal-kitun was overthrown by Mesannepada of Ur. There were then four kings in the First Dynasty of Ur: Mesannepada, Mes-kiagnuna, Elulu, and Balulu.[3] Two other kings earlier than Mes-Anepada are known from other sources, namely Mes-kalam-du and A-Kalam-du.[3] It would seem that Mes-Anepada was the son of Mes-kalam-du, according to the inscription found on a bead in Mari, and Mes-kalam-du was the founder of the dynasty.[3] A probable Queen Puabi is also known from her lavish tomb at the Royal Cemetery at Ur. The First Dynasty of Ur had extensive influence over the area of Sumer, and apparently led a union of south Mesopotamian polities.[3][4]

Ethnicity and language

Like other Sumerians, the people of Ur were a non-Semitic people who may have come from the east circa 3300 BCE, and spoke a language isolate.[5][6] But during the 3rd millennium BC, a close cultural symbiosis developed between the Sumerians and the East-Semitic Akkadians,[7] which gave rise to widespread bilingualism.[8] The reciprocal influence of the Sumerian language and the Akkadian language is evident in all areas, from lexical borrowing on a massive scale, to syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence.[8] This has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and Akkadian in the 3rd millennium BC as a Sprachbund.[8] Sumer was conquered by the Semitic-speaking kings of the Akkadian Empire around 2270 BC (short chronology), but Sumerian continued as a sacred language. Native Sumerian rule re-emerged for about a century in the Third Dynasty of Ur at approximately 2100–2000 BC, but the Akkadian language also remained in use.[9]

International trade

.jpg)

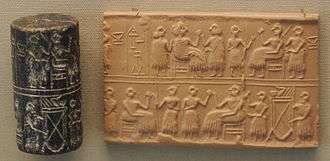

The artifacts found in the royal tombs of the dynasty show that foreign trade was particularly active during this period, with many materials coming from foreign lands, such as Carnelian likely coming from the Indus or Iran, Lapis Lazuli from the Badakhshan area of Afghanistan, silver from Turkey, copper from Oman, and gold from several locations such as Egypt, Nubia, Turkey or Iran.[11] Carnelian beads from the Indus were found in Ur tombs dating to 2600-2450, in an example of Indus-Mesopotamia relations.[12] In particular, carnelian beads with an etched design in white were probably imported from the Indus Valley, and made according to a technique developed by the Harappans.[10] These materials were used into the manufacture of beautiful objects in the workshops of Ur.[11]

The Ur I dynasty had enormous wealth as shown by the lavishness of its tombs. This was probably due to the fact that Ur acted as the main harbour for trade with India, which put her in a strategic position to import and trade vast quantities of gold, carnelian or lapis lazuli.[4] In comparison, the burials of the kings of Kish were much less lavish.[4] High-prowed Summerian ships may have traveled as far as Meluhha, thought to be the Indus region, for trade.[4]

Demise

.jpg)

According to the Sumerian King List, the First Dynasty of Ur was finally defeated, and power went to the Elamite Awan dynasty.[13] The Sumerian king Eannatum (c.2500–2400 BCE) of Lagash, then came to dominate the whole region, and established one of the first verifiable empires in history.[14]

The power of Ur would only revive a few centuries later with the Third Dynasty of Ur for a short Sumerian Renaissance.[14][15]

List of rulers

| Ruler | Image | Epithet | Length of reign | Approx. dates | Mentions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A-Imdugud) | ? | c. 26th century BC | Tomb inscriptions at the Royal Cemetery at Ur | ||

| (Ur-Pabilsag) |  | ? | c. 26th century BC | Tomb inscriptions at the Royal Cemetery at Ur | |

| (Meskalamdug) (Queen Puabi) | ? | c. 26th century BC | Dynastic beads, tomb inscriptions at the Royal Cemetery at Ur | ||

| (Akalamdug) | .jpg) | ? | c. 26th century BC | Dynastic beads, tomb inscriptions at the Royal Cemetery at Ur | |

| Mesannepada | 80 years | c. 26th century BC | Sumerian King List, Tummal Chronicle | ||

| A'annepada | "son of Mesh-Ane-pada" | ? | c. 26th century BC | Dedication tablets with inscriptions | |

| Mesh-ki-ang-Nanna | .jpg) Sumerian King List | "son of Mesh-Ane-pada" | 36 years | Sumerian King List, Tummal Chronicle | |

| Elulu | 25 years | Sumerian King List | |||

| Balulu | 36 years | Sumerian King List | |||

Sumerian King List

Only the final kings of the First Dynasty of Ur, from Mesannepada to Balulu and possibly 4 unnamed kings, are mentioned in the Sumerian King List:[16]

"... Uruk with weapons was struck down, the kingship to Ur was carried off. In Ur Mesannepada was king, 80 years he ruled; Mesh-ki-ang-Nanna, son of Mesannepada, was king, 36 years he ruled; Elulu, 25 years he ruled; Balulu, 36 years he ruled; 4 kings, the years: 171(?) they ruled. Ur with weapons was struck down; the kingship to Awan was carried off.

Artifacts

The Royal Cemetery of Ur held the tombs of several rulers of the First Dynasty of Ur.[3] The tombs are particularly lavish, and testify to the wealth of the First Dynasty of Ur.[4] One of the most famous tombs is that of Queen Puabi.[4]

_(14581033499).jpg) A gold dagger and a dagger with a gold-plated handle, Ur excavations (1900).

A gold dagger and a dagger with a gold-plated handle, Ur excavations (1900).- Reconstructed Sumerian headgear necklaces found in the tomb of Puabi, housed at the British Museum

Queen's Lyre, one of the Lyres of Ur, Ur Royal Cemetery.

Queen's Lyre, one of the Lyres of Ur, Ur Royal Cemetery.

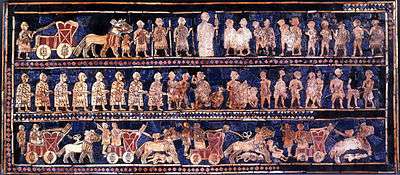

The Standard of Ur

The Standard of Ur

- Lyre of a Bull's Head from Queen Puabi's tomb. (British Museum)

.jpg) Nacre plate with anthropomorphic animals, circa 2600 BCE

Nacre plate with anthropomorphic animals, circa 2600 BCE

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Dynasty of Ur. |

References

- The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. 1970. p. 228. ISBN 9780521070515.

- Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. Infobase Publishing. 2009. p. 664. ISBN 9781438126760.

- Frayne, Douglas (2008). Pre-Sargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC). University of Toronto Press. pp. 901–902. ISBN 9781442690479.

- Diakonoff, I. M. (2013). Early Antiquity. University of Chicago Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 9780226144672.

- "The Sumerians, a non-Semitic people who perhaps came from the east" in Curtis, Adrian (2009). Oxford Bible Atlas. Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 9780191623325.. Mention of Gen 11:2 "And as people migrated from the east, they found a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there." (English Standard Version)

- Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (1979). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 392. ISBN 9780802837813.

- Hasselbach, Rebecca (2005). Sargonic Akkadian: A Historical and Comparative Study of the Syllabic Texts. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 2. ISBN 9783447051729.

- Deutscher, Guy (2007). Syntactic Change in Akkadian: The Evolution of Sentential Complementation. Oxford University Press US. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-19-953222-3.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2003), "Mesopotamia, the Invention of the City" (Penguin)

- British Museum notice: "Gold and carnelians beads. The two beads etched with patterns in white were probably imported from the Indus Valley. They were made by a technique developed by the Harappan civilization" Photograph of the necklace in question

- British Museum notice "Grave goods from Ur"

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. pp. 182–190. ISBN 9781576079072.

- "Then Urim was defeated and the kingship was taken to Awan." in Kriwaczek, Paul (2014). Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Atlantic Books. p. 136. ISBN 9781782395676.

- Incorporated, Facts On File (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. Infobase Publishing. p. 664. ISBN 9781438126760.

- Knapp, Arthur Bernard (1988). The history and culture of ancient Western Asia and Egypt. Wadsworth. p. 92. ISBN 9780534106454.

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- British Museum notice WA 121544

- Crawford, Harriet (2013). The Sumerian World. Routledge. p. 622. ISBN 9781136219115.

- Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and; Hansen, Donald P.; Pittman, Holly (1998). Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. p. 78. ISBN 9780924171550.

- James, Sharon L.; Dillon, Sheila (2015). A Companion to Women in the Ancient World. John Wiley & Sons. p. 13. ISBN 9781119025542.