Melaleuca quinquenervia

Melaleuca quinquenervia, commonly known as the broad-leaved paperbark, paper bark tea tree, punk tree or niaouli, is a small- to medium-sized tree of the myrtle family, Myrtaceae. It grows as a spreading tree up to 20 m (70 ft) tall, with its trunk covered by a white, beige and grey thick papery bark. The grey-green leaves are egg-shaped, and cream or white bottlebrush-like flowers appear from late spring to autumn. It was first formally described in 1797 by the Spanish naturalist Antonio José Cavanilles.

| Broad-leaved paperbark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Melaleuca quinquenervia growing in Woolgoolga | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Myrtales |

| Family: | Myrtaceae |

| Genus: | Melaleuca |

| Species: | M. quinquenervia |

| Binomial name | |

| Melaleuca quinquenervia | |

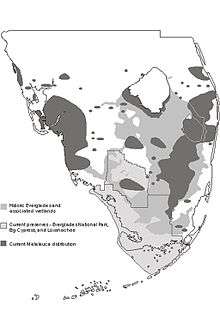

Native to New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea and coastal eastern Australia, from Botany Bay in New South Wales northwards into Queensland, M. quinquenervia grows in swamps, on floodplains and near rivers and estuaries, often on silty soil. It has become naturalised in the Everglades in Florida, where it is considered a serious weed by the USDA.

Description

Melaleuca quinquenervia is a small to medium sized, spreading tree which usually grows to a height of 8–15 m (30–50 ft) high and a spread of 5–10 m (20–30 ft) but is sometimes as tall 25 m (80 ft). Young growth is hairy with long and short, soft hairs. The leaves are arranged alternately and are flat, leathery, lance-shaped to egg-shaped, dull or grey-green, 55–120 mm (2–5 inches) long and 10–31 mm (0.4–1 inch) wide, three to eight times as long as wide.[1][2][3][4]

The flowers are arranged in spikes on the ends of branches which continue to grow after flowering, sometimes also in the upper leaf axils. The spikes contain 5 to 18 groups of flowers in threes and are up to 40 mm (2 in) in diameter and 20–50 mm (0.8–2 in) long. The petals are about 3 mm (0.1 in) long and fall off as the flower ages. The stamens are white, cream-coloured or greenish and are arranged in 5 bundles around the flower, with 5 to 10 stamens per bundle. Flowering occurs from spring to early autumn, September to March in Australia. Flowering is followed by fruit which are woody, broadly cylindrical capsules, 2.5–4 mm (0.1–0.2 in) long and clustered, spike-like along the branches. Each capsule contains many tiny seeds which are released annually.[1][2][3][4][5]

Taxonomy

The broad-leaved paperbark was first formally described in 1797 by the Spanish naturalist Antonio José Cavanilles, who gave it the name Metrosideros quinquenervia. The description was of a specimen collected "near Port Jackson" and it was published in Icones et Descriptiones Plantarum.[6][7] In 1958, Stanley Thatcher Blake of the Queensland Herbarium transferred the species to Melaleuca.[8] The specific epithet (quinquenervia) is from the Latin quinque meaning "five" and nervus, "vein", referring to the leaves usually having five veins.[1][3]

The common names broad-leaved paperbark, broad-leaved tea tree or simply paperbark or tea tree are used in Australia, and punk tree is used in the United States.[5] It is known as niaouli, itachou (paicî) and pichöö (xârâcùù) in New Caledonia.[9]

Distribution and habitat

In Australia, Melaleuca quinquenervia occurs along the east coast, from Cape York in Queensland to Botany Bay in New South Wales. It grows in seasonally inundated plains and swamps, along estuary margins and is often the dominant species. In the Sydney region it grows alongside trees such as swamp mahogany (Eucalyptus robusta) and bangalay (E. botryoides). It grows in silty or swampy soil and plants have grown in acid soil of pH as low as 2.5.[10]

Broad-leaved paperbark is also native in the southern part of Indonesian West Papua and Papua New Guinea. It is widespread in New Caledonia, including Grand Terre, Belep, Isle of Pines and Maré.[9] It is a component of the savannah of western New Caledonia, scattered trees dotting the grassland habitat and its spread through this landscape might have been facilitated by human fire regimes.[11] Major threats to M. quinquenervia are housing developments, roads, sugar cane and pine plantations. Remnants in Australia are not protected in reserves, with majority of its woodland located in private property where clearing continues.[12]

Melaleuca quinquenervia has been introduced as an ornamental plant to many tropical areas of the world, including Southeast Asia, Africa and the Americas and has become a weed in many areas.[13]

Ecology

Melaleuca quinquenervia resprouts vigorously from epicormic shoots after bushfire, and has been recorded flowering within weeks of being burnt. Trees can live for over 100 years, with 40-year-old trees achieving a trunk circumference of 2.7 m (9 ft) in cultivation.[10]

The flowers serve as a rich source of nectar for other organisms, including fruit bats, a wide range of insect and bird species,[5] such as the scaly-breasted lorikeet (Trichoglossus chlorolepidotus).[14] The grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) and little red flying-fox (P. scapulatus) consume the flowers.[15]

Status in the United States

Melaleuca quinquenervia was introduced into Florida as early as 1900 when specimens were first planted near Orlando.[16] There were two major introductions, one by J. Gifford to the East Coast in 1907, and one by A.C. Andrews to the west coast in 1912.[17] The South Florida Water Management District has recorded Melaleuca around the areas where they were originally introduced: southwest of Broward and northern Dade County on the east coast and southern Lee County and north of Collier County on the west coast.[18] The species is mainly found in the more frost-free areas of south Florida and only rarely in the warmer coastal areas of Pasco County.[19]

Melaleuca quinquenervia has been classified by the United States Department of Agriculture as a noxious weed in six US states (Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Massachusetts, Oklahoma and Texas), as well as federally.[20] It is an abundant exotic invasive plant in the Everglades.[21] Its unchecked expansion in South Florida is one of the most serious threats to the integrity of the native ecosystem.[22] This tree takes over sawgrass marshes in the Everglades turning the area into a swamp.[23] Melaleuca causes severe ecological impacts, including displacing native species, modification of hydrology, alteration of soil resources, reducing native habitat value and changing the fire regime.[24]

An experiment comparing the quantity of seeds held in the canopies of Melaleuca trees in Australia and Southern Florida found that the viability and amount of seeds found in Australia were lower when compared to those in Florida.[25] Australian Melaleuca trees held 5,000 seeds with less than 20 viable, and Florida Melaleucas contained 13,000 seeds, with greater than 1,200 viable.[25] So without a predator reducing the amount of reproductive structures in Melaleuca it can reproduce unchecked. The release from natural enemies will cause the invasive exotic plant to evolve, improving its performance in the new area.[26] This idea is supported by the results of a study on Melaleuca done by Pratt et al. (2005) showing that damage by herbivores reduced success in the following season as the reproductive structures declined by 80% with 54% less fruits. Biocontrol agents that have been released in Florida are the Oxyops vitiosa (weevil) and Boreioglycapsis (melaleuca psyllid). These insects are native to Australia and serve to reduce the growth and reproduction of M. quinquenervia by feeding on young expanding leaves and phloem of the tree.[27][28]

Punk tree is known for its capability to withstand floods and droughts.[21] If there is a canopy gap created by a flood or some other disturbance Melaleuca will establish to make use of the extra light.[23] In physically disturbed sites, flourishing invaders have high colonisation abilities.[29] For example, Melaleuca is constantly thinning itself of small branches and twigs and this causes many seeds to fall all the time along with the litter,[30] so it is always dispersing its potential offspring. Melaleuca is also capable of living in disturbed habitats such as improved pasture, idle farmland,[24] and canal affected areas. The climate in south Florida is similar to that in its native Australia, beginning with geographic locations at latitude 26º N about halfway between Lake Okeechobee and the tip of mainland Florida; in Australia the latitude 26º S lies just north of Brisbane in south Queensland. Both regions have subtropical to tropical climate. As a result of this, Melaleuca has almost been pre-adapted for south Florida. Fire thrives in these environments and seed dispersal is displaced when fire occurs.[12] Melaleuca bloom five times throughout the year, with individual branches supporting three out of the five. Each flower part can drop about 30–70 small seed capsules which can be viable for almost ten years. It was determined that each capsule contained about 200–300 seeds, dropping rapidly and can be found 170 m from the source tree. The seeds of M. quinquenervia appear to be well adapted to wet/dry seasonal climates and can even germinate underwater on soil substrate.[12]

Recent studies comparing specific leaf area of invasive exotic plants with exotic non-invasive plants and native plants in relation to disturbances have shown that invasive have a larger specific leaf area than the other plants.[29] This allows for faster growth, these results held up by many supporting studies have allowed Lake and Leishman to infer that invasive species are so successful because of their skill for fast growth, and greater capacity to capture and retain space. Melaleuca has definitely been shown to have these traits, such as in the Everglades where the Melaleuca population increased 50-fold between the early 1970s and the late 1990s.[24]

Chemistry

M. quinquenervia have been shown to occur in distinct chemical forms. These forms or chemotypes are characterised by the organic compounds terpenes. Chemotype 1 has acyclic foliar terpenes, with concentrations of sesquiterpene E-nerolidol 74–95% of total oil and also monoterpene linalool.[31] Chemotype 2 has high concentration of cyclic foliar terpenes, in particular sesquiterpene viridiflorol with 13-66% of total oil. Chemotype 2 also includes monoterpenes 1,8-cineole and α-terpineol.[31]

Grandinin is an ellagitannin also found in leaves of M. quinquenervia.[32]

Uses

Melaleuca quinquenervia has multiple uses, and is widely used traditionally by indigenous Australians. A brew was made from the bruised young aromatic leaves to treat colds, headaches and general sickness.[33] The steam distilled leaf oil of the cineole chemotype is also used externally for coughs, colds, neuralgia, and rheumatism.[34] A nerolidol and linalool chemotype is also cultivated and distilled on a small scale for use in perfumery.

The paper-like bark is used traditionally for making coolamons, shelter, wrapping baked food and lining ground ovens.[5] The nectar is extracted traditionally by washing in coolamons of water which is subsequently consumed as a beverage. The scented flower also produces a light to dark amber honey depending on the district. It is strongly flavoured and candies readily and is not regarded as a high quality honey, but nevertheless is popular.[35]

Melaleuca quinquenervia is sometimes used as a bonsai.[36]

The timber is tolerant of being soaked, and is used in fences.[37]

Melaleuca quinquenervia is often used as a street tree or planted in public parks and gardens, especially in Sydney.[38] In its native Australia, it is excellent as a windbreak, screening tree and food source for a wide range of local insect and bird species.[5][39] It can tolerate waterlogged soils.[37] It is regarded by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) as an invasive weed in Florida where it was introduced to drain swamps.

The essential oil of Melaleuca quinquenervia is used in a variety of cosmetic products especially in Australia. The oil is reported in herbalism and natural medicine to work as an antiseptic and antibacterial agent, to help with bladder infections, respiratory troubles and catarrh. The oil has a very low (level 0) hazard score on the Cosmetic Safety Database.[40]

Gallery

red-flowered form in Brisbane Botanic Gardens

red-flowered form in Brisbane Botanic Gardens M. quinquenervia - MHNT

M. quinquenervia - MHNT_Paperbark.jpg) M. quinquenervia bark

M. quinquenervia bark M. quinquenervia white form in New Caledonia

M. quinquenervia white form in New Caledonia

See also

- Invasive plants of Australian origin

- Melaleuca leucadendra, also commonly called "paper bark tree"

References

- Brophy, Joseph J.; Craven, Lyndley A.; Doran, John C. (2013). Melaleucas : their botany, essential oils and uses. Canberra: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. pp. 302–303. ISBN 9781922137517.

- Holliday, Ivan (2004). Melaleucas : a field and garden guide (2nd ed.). Frenchs Forest, N.S.W.: Reed New Holland Publishers. pp. 238–239. ISBN 1876334983.

- Wrigley, John W.; Fagg, Murray (1993). Bottlebrushes, paperbarks & tea trees, and all other plants in the Leptospermum alliance. Pymble, N.S.W.: Angus & Robertson. p. 297. ISBN 0207168679.

- Wilson, Peter G. "Melelauca quinquenervia". Royal Botanic Garden Sydney: plantnet. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- Elliot, Rodger W.; Jones, David L.; Blake. Trevor (1993). Encyclopaedia of Australian Plants Suitable for Cultivation:Volume 6 – K-M. Port Melbourne: Lothian Press. p. 359. ISBN 0-85091-589-9.

- "Metrosideros quinquenervia". APNI. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- Cavanilles, Antonio Jose (1797). Icones et Descriptiones Plantarum (Volume 4, No. 1). Madrid. p. 19. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- "Melaleuca quinquenervia". APNI. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- "Melaleuca quinquenervia". Endemia, New Caledonia. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- Benson, Doug; McDougall, Lyn (1998). "Ecology of Sydney plant species:Part 6 Dicotyledon family Myrtaceae" (PDF). Cunninghamia. 5 (4): 969.

- Dieter Mueller-Dombois; Francis Raymond Fosberg (1998). Vegetation of the tropical Pacific islands. Springer. p. 159. ISBN 0-387-98313-9. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- C.E., Turner; T. D. Center; D. W. Burrows; G. R. Buckingham (1998). "Ecology and management of Melaleuca quinquenervia, an invader of wetlands in Florida, USA. Wetlands Ecology and Management". 5: 165–178. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Melaleuca quinquenervia (paperbark tree)". Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- Lepschi BJ (1993). "Food of some birds in eastern New South Wales: additions to Barker & Vestjens". Emu. 93 (3): 195–99. doi:10.1071/MU9930195.

- Eby P (1995). The biology and management of flying foxes in NSW. Hurstville, NSW: National Parks & Wildlife Service.

- Meskimen, G. F. (1962). "A silvical study of the melaleuca tree in south Florida". Univ. FL, Gainesville, FL. MS Thesis: 177. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rothra, E.O. (1972). "John Clayton Gifford on preserving tropical Florida". Miami Press, Coral Gables.

- Wheeler, G; K.M. Ordung (2006). "Lack of an induced response following fire and herbivory of two chemotypes of Melaleuca quinquenervia and its effect on two biological control agents". Biological Control. 39 (2): 154–161. doi:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2006.05.016.

- Jarvis, BobbiJo. "Melaleuca – An Invasive Tree of Florida". University of Florida – Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- "Melaleuca quinquenervia". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- Serbesoff-King, K (2003). "Melaleuca in Florida: a literature review on the taxonomy, distribution, biology, ecology, economic importance and control measures". Journal of Aquatic Plant Management. 41: 98–112.

- Laroche FB, Ferriter AP (1992). "The rate of expansion of Melaleuca in South Florida". Journal of Aquatic Plant Management. 30: 62–65.

- Zedler, J. B.; Kercher, Suzanne (2004). "Causes and consequences of invasive plants in wetlands: Opportunities, opportunists, and outcomes". Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 23: 431–52. doi:10.1080/07352680490514673.

- Mazzotti, FJ, Center TD, Dray FA, Thayer D (1997). "Ecological consequences of invasion by Melaleuca quinquenervia in south Florida wetlands: Paradise damaged, not lost". University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Cooperative Extension Service Bulletin (SS–WEC–123): 1–5.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Rayamajhi, M. B.; Van, T. K.; Center, T. D.; Goolsby, J. A.; Pratt, P. D.; Racelis, A. (2002). "Biological attributes of the canopy-held Melaleuca seeds in Australia and Florida, US". Journal of Aquatic Plant Management. 40: 87–91.

- Hierro JL, Maron JL, Callaway RM (2005). "A biogeographical approach to plant invasions: the importance of studying exotics in their introduced and native range". Journal of Ecology. 93 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1111/j.0022-0477.2004.00953.x.

- Wheeler, G.S. (2005). "Chemotype variation of the weed Melaleuca quinquenervia influences the biomass and fecundity of the biological control agent Oxyops vitiosa". Biological Control. 36: 121–128. doi:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2005.10.005.

- Padovan, A.; Keszei, A.; Koellner, T. G.; Degenhardt, J.; Foley, W. J. (2010). "The molecular basis of host plant selection in Melaleuca quinquenervia by a successful biological control agent". Phytochemistry. 71 (11–12): 1237–1244. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.05.013. PMID 20554297.

- Lake JC, Leishman MR (2004). "Invasion success of exotic plants in natural ecosystems: the role of disturbance, plant attributes and freedom from herbivores". Biological Conservation. 117 (2): 215–26. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00294-5.

- Van, T. K.; Rayachhetry, M. B.; Center, T. D.; Pratt, P. D. (2002). "Litter dynamics and phenology of Melaleuca quinquenervia in South Florida". Journal of Aquatic Plant Management. 40: 22–27.

- Ireland, B.F.; D.B. Hibbert; R.J. Goldsack; J.C. Doran; J.J. Brophy (2002). "Chemical variation in the leaf essential oil of Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S.T. Blake". Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 30: 457–470. doi:10.1016/s0305-1978(01)00112-0.

- Moharram, F. A. (2003). "Polyphenols ofMelaleuca quinquenervia leaves - pharmacological studies of grandinin". Phytotherapy Research. 17: 767–773. doi:10.1002/ptr.1214. PMID 12916075.

- Maiden, J.H., The Forest Flora of New South Wales, vol. 1, Government Printer, Sydney, 1904.

- Blake, S.T., Contributions from the Queensland Herbarium, No.1, 1968.

- Cribb, A.B. & J.W., Useful Wild Plants in Australia, Collins 1982, p. 23, ISBN 0-00-636397-0.

- "Australian Plants as Bonsai - Melaleuca quinquenervia". Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Halliday, Ivan (1989). A Field Guide to Australian Trees. Melbourne: Hamlyn Australia. p. 262. ISBN 0-947334-08-4.

- Halliday, Ivan (2004). Melaleucas: A Field and Garden Guide. Sydney: New Holland Press. p. 238. ISBN 1-876334-98-3.

- Elliot, Rodger (1994). Attracting Wildlife to Your Garden. Melbourne: Lothian Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-85091-628-3.

External links

- PCA Alien Plant Working Group – Melaleuca quinquenervia

- Species Profile - Melaleuca (Melaleuca quinquenervia), National Invasive Species Information Center, United States National Agricultural Library.