Medici Fountain

The Medici Fountain (French: la fontaine Médicis) is a monumental fountain in the Jardin du Luxembourg in the 6th arrondissement in Paris. It was built in about 1630 by Marie de' Medici, the widow of King Henry IV of France and regent of King Louis XIII of France. It was moved to its present location and extensively rebuilt in 1864-66.

Italian influence in Paris in the 17th century

The period between the regency of Catherine de' Medici in France (1559–1589) and that of Marie de' Medici (1610–1642) saw a great flourishing of the Italian mannerist style in France, A community of artists from Florence, including the sculptor Francesco Bordoni, who helped design the statue of King Henry IV of France built on the Pont Neuf, and fountain technician Thomas Francini, who had worked on fountains in the new gardens of the Medici villas in Florence and Rome, found eager royal patrons in France. Soon features of the Italian Renaissance garden, such as elaborate fountains and the grotto, a simulated cave decorated with sculpture, appeared in the first Gardens of the French Renaissance at Fontainebleau and other royal residences.[1]

Construction

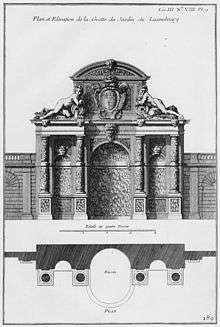

Marie de' Medici, as widow of Henry IV and mother and regent of King Louis XIII of France, began construction of her own palace, which she called the Palais des Medicis, between 1623 and 1630, on the left bank of Paris. The new palace was modeled after the Palazzo Pitti in her native Florence, and the gardens around the palace were modeled after those of the Boboli Gardens in Florence. The Palace was the work of architect Salomon de Brosse, but the fountain and grotto was most probably the work of Tommaso Francini, the Intendant General of Waters and Fountains of the King.[2] Francini, who emigrated to France at the invitation of Henry IV in 1598 and was naturalized in 1600, had built grottos and fountains in the Italian style for the marquis de Gondi and for the royal chateau of Henry IV at Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

The first difficulty of construction was the lack of water in the Left Bank of Paris. Unlike the Right Bank, where the water table was near the surface, and there were many wells and two aqueducts which served the city, the water table on the Left Bank was deep underground and all water had to be carried from the Seine. As a result, the city had expanded far from the Right Bank of the Seine, but had hardly grown at all on the Left Bank. This problem was finally solved by the construction of the aqueduct of Arcueil, between 1613-1623.[3]

19th Century modifications

After the death of Marie de' Medici, the Palace and fountain went through a series of owners. By the middle of the 18th century, when the fountains of Versailles and the Garden à la française were in fashion, the Medici Fountain fell into disrepair. The two original statues at the top of the fountain, by the sculptor Pierre Biard, two nymphs pouring water from pitchers, had disappeared, and the wall of the Orangerie, against which the fountain was placed, was crumbling.

In 1811, at the instructions of Napoleon Bonaparte, the grotto was restored by the neoclassical architect Jean Chalgrin, the architect of the Arc de Triomphe, who replaced the simple water fountain in the niche of the grotto with two streams of water, and added a white marble statue representing Venus in her bath.[4]

In 1864, during the Second French Empire, Baron Haussmann planned to build the rue de Medicis through the space occupied by the fountain. The lateral arcades of the fountain and the crumbling old orangerie behind it had already been torn down in 1855. From 1858 to 1864, The new architect, Alphonse de Gisors, moved the fountain thirty meters to make room for the street, and radically changed its setting and appearance.

Since the fountain no longer stood against a wall, the Fontaine de Léda, displaced from another neighborhood, was placed directly behind it. (See the Fountain of Leda, below.) He replaced the two original statues of nymphs at the top of the statue with two new statues, representing the Rivers Rhone and Seine. He restored the coat of arms of the Medici family over the fountain, which had been defaced during the Revolution. He inserted two statues into the niches, one representing a faun and the other a huntress, above which are two masks, one representing comedy and the other tragedy. He removed the simple basin and water spout which had been in the niche and replaced them with a long tree-shaded basin. Finally, he removed the statue of Venus and replaced her with a group of statues by Auguste Ottin, representing the giant Polyphemus, in bronze, discovering the lovers Acis and Galatea, in white marble. That is the fountain as it appears today.[5]

The Hidden Fountain - the Fountain of Léda

The fountain which Gisors placed behind the Medici Fountain had a history of its own. The Fontaine de Léda had been constructed in 1806-1809, during the First Empire, at the corner of rue Vaugirard and rue du Regard. It was the work of architect François-Jean Bralle and sculptor Achille Valois. The bas-relief of the fountain depicts the story of Leda and the Swan; Leda holds the swan on her knees, and the figure of Amor is shooting an arrow at her from the corner of the sculpture. Water flowed from the beak of the swan down to a hemispherical basin at the foot of the fountain.

In 1856, when Baron Haussmann wanted to extend the rue de Rennes, the chief of the service of Promenades and Plantations of Paris, Gabriel Davioud, who designed most of the city's fountains, benches, gates and other urban architectural decorations during the Second Empire, and who was himself a sculptor, wanted to preserve the fountain, and in 1858 he had it moved to the Jardin du Luxembourg. Since it was a wall fountain, it had to be attached to something, so he placed it on the back of the Medici Fountain, where it still remains, unnoticed by passers-by.[6] (See also Fountains in Paris.).

References

- Luigi Gallo, La présence italianne au 17e siècle, in Paris et ses fontaines de la Renaissance à nos jours, Collection Paris et son patrimoine, Delegation a l'action artistique de la Ville de Paris.

- See Yves Marie Allain and Janine Christiany, L'art des jardins en Europe, and Luigi Gallo in Paris et ses Fontaines, both of which attribute the fountain to Francini. De Brosse is sometimes credited with designing the fountain, but he died in the same year the fountain was built, and before his death he was involved in a lawsuit with Marie de' Medici over non-payment of his fee; court documents detailed all the work he had done for the Queen, and there was no mention of the fountain. See Luigi Gallo, pg. 56.

- For a description of the water shortage on the Left Bank, see Philippe Cebron de Lisle, Paris en quête d'eau, in Paris et ses Fontaines

- A. Duval, Fontaine Medicis, Les fontaines de Paris, 1813.

- Luigi Gallo, pg. 57

- See Katia Frey, L'enterprise napoléonienne, in Paris et ses fontaines, pg. 115.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fontaine Médicis. |

- Paris et ses fontaines, de la Renaissance à nos jours, texts assembled by Dominque Massounie, Pauline-Prevost-Marcilhacy and Daniel Rabreau, Délegation à l'action artistique de la Ville de Paris, Collection Paris et son Patrimoine, Paris, 1995.

- L'Art des jardins en Europe, Yves-Marie Allain and Janine Christiany, Citadelles & Mazenod, Paris, 2006