McMillan Reservoir

The McMillan Reservoir is a reservoir in Washington, D.C. that supplies the majority of the city's municipal water. It was originally called the Howard University Reservoir or the Washington City Reservoir, and was completed in 1902 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.[1] The reservoir was built on the site of Smith Spring, one of the springs previously used for drinking water. Washington's earliest residents relied on natural springs but this came to be inadequate as the city's population grew. In 1850, Congress determined that the Potomac River should be the city's principal source of water.

| McMillan Reservoir | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Coordinates | 38.9251°N 77.0173°W |

| Type | reservoir |

| Primary inflows | Washington Aqueduct |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Surface area | 25 acres (10 ha) |

Construction history

Washington Aqueduct

A Congressionally funded engineering study was conducted to determine the most available mode of supplying water to the city. Work and study conducted under the leadership of Lieutenant Montgomery C. Meigs culminated into the development of the Washington Aqueduct which began operations on January 3, 1859.[2] (Initially the system provided water to the city from the Little Falls Branch in Maryland, until the aqueduct construction was completed.) Regular water service from the Potomac River source through the aqueduct commenced in 1864.

Washington City Tunnel

In the early years of operation the water was routed through the system's two earlier-built reservoirs, Dalecarlia and Georgetown, which were designed to settle sediment out of the water. In 1873 the Army began construction of a new water supply tunnel, led by Garrett Lydecker, a major in the Army Corps of Engineers.[3] The tunnel was known as the Washington City Tunnel, to provide more storage, sedimentation and distribution capacity for the system. Lydecker predicted the tunnel would cost about $53,000 to build.[4]

Construction of the tunnel was halted in the 1880s due to a variety of problems including funding shortages, cost overruns, bribery and fraud associated with the construction process.[2]:73,83 During that period some improvements were made to the Dalecarlia portion of the system, and work on the tunnel finally resumed in 1898.

The tunnel was completed in 1901, after an additional $800,000 investment[4], and the McMillan Reservoir began operation in 1902.

Filtration plant

All the District's water needs were thought to have been quenched by the water aqueduct system, but by 1902 it became apparent that it was no longer adequate. To handle population growth and municipal sanitation needs, officials added the McMillan Sand Filtration Site in 1905. This facility implemented an innovative water purification system relying on sand instead of chemicals to filter 75 million gallons (280 million liters) per day. It helped quell typhoid epidemics and other communicable diseases throughout the city.

In 1907 the reservoir and filtration plant were named in honor of Senator James McMillan of Michigan, who chaired the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia and supported development of the water supply facilities. The Congress officially designated the site as a park in March 1911.[5]

Subsequent improvements to the city water system were initiated beginning in the 1920s. The regular use of chlorine as a disinfectant began in 1923 at the McMillan filtration plant. Another treatment plant was completed in 1928, and this was built adjacent to the Dalecarlia Reservoir.[2]:101–105 The growth of the city population led to further expansions at the Dalecarlia site in the 1950s.

McMillan Fountain

The McMillan Fountain is a public artwork by American artist Herbert Adams located on the Reservoir grounds. The fountain, completed in 1912 and dedicated in October 1919, consists of a bronze The Three Graces placed upon a pink granite base. Cast by Roman Bronze Works, the fountain was originally part of a large landscape setting designed by Charles A. Platt. A tribute to James McMillan, the fountain was paid for by citizens of Michigan, who raised $25,000 by way of pennies, nickels and dimes donated by public school children. Congress also funded totaling $15,000 towards the completion.[6][7]

Recent developments

In 1941, citing security concerns, the entire site was permanently closed and fenced off due to fear of sabotage.[8] The property remained closed to the public, but supplied the city with filtered water into the 1980s. In 1986, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers decommissioned the site and declared it surplus. The old water treatment site was purchased by the District of Columbia from the federal government in 1987 for $9.3 million, and since has deteriorated due to lack of maintenance. The question of what to do with the property is up for debate.[9]

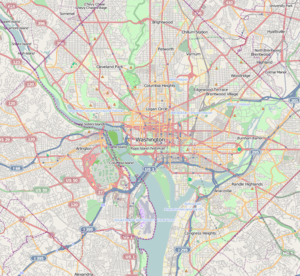

The 25 acre (100,000 m²) McMillan Reservoir, located between Michigan Avenue, North Capitol Street, and First Street in Northwest Washington, D.C., was designated a DC Historic Landmark in 1991.[10][11] In 2000, and again in 2005, it was placed on the "List of Most Endangered Properties."

In 2006, a request for quotation (RFQ) to redevelop the McMillan site was released with five responses being received by the D.C. government. In 2007, Vision McMillan Partners, composed of Trammell Crow Company, Jair Lynch Development Partners, and EYA, was selected as the winning bid.

Friends of McMillan Park and Save McMillan Action Coalition, community organizations, generated local opposition and activism, leading to court action, delaying and preventing the project from beginning.[12] In 2016, courts sided with community activists and rejected the DC Zoning Commission's approval of a $720 million project to transform the site into retail, office and residential space.[13]

The D.C. Court of Appeals cleared the $720 million project to commence in July 2019.[14] Preliminary demolition work began in September 2019, being fiercely contested by opposition groups and protesters.[15] In December 2019, a restraining order was filed to stop work on the site.[16]

References

- Scott, Pamela (2007), "Capital Engineers: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the Development of Washington, D.C., 1790-2004." Archived 2012-02-26 at the Wayback Machine p. 175. Washington, DC: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Publication No. EP 870-1-67.

- Ways, Harry C. (1996), "The Washington Aqueduct: 1852-1992," Baltimore, MD: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District.

- Rowl, HistoryBy DW; sAugust 20; 2018 27. "The fascinating story of DC's aqueducts and reservoirs". ggwash.org. Retrieved 2020-01-02.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "The Lydecker Tunnel Fiasco". Architect of the Capital. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- United States. An Act Making appropriations to provide for the expenses of the government of the District of Columbia for the fiscal year ending June thirtieth, nineteen hundred and twelve, and for other purposes. Chapter 192, Public Law No. 441. 61st Congress, Session III. H. R. 31856. March 2, 1911. 36 Stat. 983

- Louise Todd Ambler & Marilyn Gage Hyson (2003). "McMillan Fountain (sculpture)". Untitled Checklist. Smithsonian. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- Somma, Thomas P. "The McMillan Memorial Fountain: A Short History of a Lost Monument", Washington History, Vol 14, No. 2, pp. 96-107.

- Goldchain, Michelle (2016-12-07). "McMillan Sand Filtration site's history, in a timeline". Curbed DC. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- Layton, Lyndsey (April 22, 2006). "What to Do with What Lies Beneath?". Washington Post. p. B01.

- "McMillan Park Reservoir Historic District | op". planning.dc.gov. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- "Washingtoniana: The McMillan Reservoir | Washingtonian (DC)". Washingtonian. 2008-10-16. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- Goldchain, Michelle (2016-12-05). "McMillan Sand Filtration site groundbreaking begins this Wednesday, despite local opposition". Curbed DC. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- "The fight to develop McMillan Park continues: Court rules against zoning commission".

- "After Years Of Limbo, McMillan Development Gets The Green Light". DCist. Archived from the original on 2020-01-02. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- "Demolition Work Nears for McMillan Site Ahead of Redevelopment". DC Post. 2019-11-02. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- "Neighbors fight to block development of former sand filtration site". WTOP. 2019-12-20. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to McMillan Reservoir. |

- D.C. Preservation League

- D.C. Water and Sewer Authority

- Washington Aqueduct - U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

- Pictures of the McMillan slow sand plant, with history