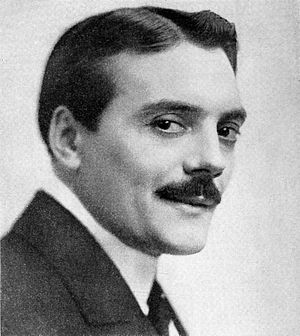

Max Linder

Gabriel-Maximilien Leuvielle (16 December 1883 – 1 November 1925), known professionally as Max Linder (French: [maks lɛ̃.dɛʁ]), was a French actor, director, screenwriter, producer and comedian of the silent film era. His onscreen persona "Max" was one of the first recognizable recurring characters in film. He has also been cited as the "first international movie star"[1] and "the first film star anywhere".[2]

Max Linder | |

|---|---|

Linder (1919) | |

| Born | Gabriel-Maximilien Leuvielle 16 December 1883 |

| Died | 1 November 1925 (aged 41) |

| Occupation | Actor, film director, screenwriter, film producer, comedian |

| Years active | 1899–1925 |

| Spouse(s) | Hélène "Jean" Peters (m.1923) |

| Children | 1 |

Born in Cavernes, France to Catholic parents, Linder grew up with a passion for theater and enrolled in the Conservatoire de Bordeaux in 1899. He soon received awards for his performances and continued to pursue a career in the legitimate theater. He became a contract player with the Bordeaux Théâtre des Arts from 1901 to 1904, performing in plays by Molière, Pierre Corneille and Alfred de Musset.

From the summer of 1905, Linder appeared in short comedy films for Pathé, at first usually in supporting roles. His first major film role was in the Georges Méliès-like fantasy film The Legend of Punching. During the following years, Linder made several hundred short films portraying "Max", a wealthy and dapper man-about-town frequently in hot water because of his penchant for beautiful women and the good life. Starting with The Skater's Debut in 1907, the character became one of the first identifiable motion-picture characters who appeared in successive situation comedies. By 1911, Linder was co-directing his own films (with René LePrince) as well as writing the scripts.

Linder enlisted at the outbreak of the First World War, and worked at first as a dispatch driver and entertainer. During his service, he was injured several times, and the experiences reportedly had a devastating effect on him both physically and mentally.[3] It was during this time he suffered his first outbreak of chronic depression.

Life and career

Early life

Linder was born Gabriel-Maximilien Leuvielle near Saint-Loubès, Gironde. His parents were wealthy vineyard owners and expected Linder to take over the family business; his older brother Maurice (born 28 June 1881) had become a celebrated national rugby player. But Linder grew up with a passion for theater, and was enthralled by the traveling theater and circus performances that occasionally visited his town. He later wrote that "nothing was more distasteful to me than the thought of a life among the grapes."[4]

Early career 1899–1905

In 1899, Linder enrolled in the Conservatoire de Bordeaux and quickly won awards for first prize in comedy and second prize in tragedy. He continued to pursue a career in the theater and became a contract player with the Bordeaux Théâtre des Arts from 1901 to 1904, performing in plays by Molière, Pierre Corneille and Alfred de Musset. At the same time that he was performing in serious dramatic theater, he became friends with Charles le Bargy of the Comédie-Française. Le Bargy encouraged Linder to audition for the Conservatoire de Paris in 1904. Linder was rejected and began appearing in less prestigious theaters such as the Olympia Theater and the Théâtre de l'Ambigu.[4]

By 1905, he had adopted his stage name of Max Linder and used it in several theatrical performances. Also during this period, Linder applied for work at Pathé Frères in Vincennes at the suggestion of film director Louis Gasnier and began appearing in small bit parts, mostly in slapstick comedies. Linder continued to appear on the stage for the next two years and was not a significant film star at first. However, an often-told legend about the origins of Linder's film career is that French film producer Charles Pathé personally saw Linder on the stage and wrote him a note that read "In your eyes lies a fortune. Come and act in front of my cameras, and I will help make it."[4]

Film career 1905–1916

From 1905 to 1907, Linder appeared in dozens of short comedy films for Pathé, usually in a supporting role. His first noticeably larger film role was in The Young Man's first outing in 1905. He also appeared in Georges Méliès-like fantasy films such as Serpentine Dances and The Legend of Punching, his first leading role. His rise to stardom commenced in 1907 when Pathé's slapstick star René Gréhan left the company to join Éclair. Gréhan's screen character was Gontran, whose persona included high-society clothing and a dandy-ish demeanor. Linder was chosen to take over the characterization for Pathé, and the style of dress and personality of Gréhan's character became his trademark. Film critic David Robinson described Linder's screen persona as "no grotesque: he was young, handsome, debonair, immaculate...in silk hat, jock coat, cravat, spats, patent shoes, and swagger cane."[4] Linder made more than one hundred short films portraying "Max", a wealthy and dapper man-about-town frequently in hot water because of his penchant for beautiful women and the good life. With this character, he had created one of the first identifiable motion-picture characters who appeared in successive situation comedies.

Linder's first appearance as "Max" was in The Skater's Debut in 1907. Lake Daumesnil in Paris had frozen over and director Louis Gasnier filmed Linder in his new attire, with Linder improvising the rest. In the film, "Max" falls about and does a rendition of "the windmill routine" by spinning his cane around, predating Charlie Chaplin's version in The Rink by nine years. Pathé was unimpressed with the film and re-shot parts of it, and it was not popular with audiences when released. Soon afterwards, Gasnier left Pathé and moved to Italy, leaving Linder without a supporter at Pathé; he made few films in 1908.[4] His luck began to change when Pathé's top comedy star, André Deed, left to work with the Italian film company Itala, leaving Linder as the company's leading comedic actor. Later in 1909, Gasnier returned from Italy and immediately began working with Linder again. The team made several shorts in 1909 with Linder in various roles, such as a blind elderly man and a coquettish young woman. But they soon discovered that the character of "Max" was the most popular with audiences and stuck with him from then on. Among the popular "Max" films made by Linder and Grasnier in 1909 are A Young Lady Killer and The Cure for Cowardice[4]

By 1910, Linder had proved himself to Pathé and was quickly becoming one of the most popular film actors in the world. When Gasnier was sent to the United States later that year to oversee Pathé's productions there, Lucien Nonguet took over as Linder's director. Together they made such films as Max takes a bath and the autobiographical Max Linder's Film Debut, which fictitiously recreates the legend of Linder's early film career and includes Charles Pathé as himself.

By the end of the year, Linder had become the most popular film actor in the world. Although actress Florence Lawrence is often referred to as "The First Movie Star" in the United States, Linder appears to be the very first worldwide movie star with a major following. In Russia, he was voted the most popular film actor, ahead of Asta Nielsen. He also had a Russian impersonator, Zozlov, and a devoted fan in Czar Nicholas II. Another professed fan was British playwright George Bernard Shaw. The first feature film ever made in Bulgaria was a remake of one of Linder's earlier movies. He was offered $12,000 to spend a month in Berlin making public appearances with his film screenings, but had to decline for health reasons. In France, a Max Linder movie theater had opened in Paris.

At the height of his fame, Linder ended 1910 with a serious illness. He was forced to stop making films when appendicitis left him bedridden, and some newspapers reported that he had died. He eventually recovered the following spring and began making films again in May 1911.[4]

In 1911, Linder returned to filmmaking and began co-directing his own films (with René LePrince) as well as writing the scripts. By 1912, he was the solo director of his films. Gaining complete control over his own films brought positive results both critically and commercially; the films Linder made during this period are generally considered to be his best. Max, Victim of Quinine is considered by film critic Jean Mitry to be "his masterpiece."[4] In the film, an intoxicated "Max" gets into numerous fights with such dignitaries as the Minister of War, an ambassador and the police commissioner, all of whom challenge him to a duel and present him with their business cards. Eventually "Max" is apprehended by the police, who attempt to return him to his residence, but end up mistakenly taking him to the homes of the various men whom he had previously fought with.[4]

The universality of silent films brought Linder fame and fortune throughout Europe, making him the highest paid entertainer of the day, with a salary increase of 150,000 francs (the average monthly salary in France was 100 francs at the time). He began touring Europe with his films from 1911 to 1912, including Spain, where he entertained thousands of fans at the Barcelona railway station, Austria, and Russia, where he was accompanied on piano by a young Dimitri Tiomkin. In 1912 after the tour, Linder demanded and received a salary of one million francs a year, and Charles Pathé used the huge sum to generate publicity, with an ad reading "We understand that the shackles which bind Max Linder have attained the value of one million francs a year...the imagination boggles at such a figure!"[4] This set a precedent in the entertainment industry for actors' salaries that would become a staple of the Hollywood system, but privately Pathé nicknamed Linder "The Napoleon of the Cinema".[4]

The high point of Linder's career was from 1912 to 1914. His films were made with increased skill and "Max" was at his funniest. He made such films as Max Virtuoso, Max Does Not Speak English, Max and His Dog, Max's Hat and Max and the Jealous Husband. His ensemble of actors included Stacia Napierkowska, Jane Renouardt, Gaby Morlay, and occasional performances from the young actors Abel Gance and Maurice Chevalier. Linder had given Chevalier his start in movies, but the silent medium did not suit Chevalier, who stuck to the stage until the all-singing all-dancing features came in, many years later.

The outbreak of World War I brought a temporary end to Linder's film career in 1914, but not before he made the short patriotic film The Second of August that year.[4] Linder attempted to enlist in the French army, but was physically unfit for combat duty. Instead he worked as a dispatch driver between Paris and the front lines. Many conflicting stories about the reasons behind his dismissal from the army exist, including that he was shot through the lung, and seriously wounded. Initially, it was reported by one newspaper that he had been killed; Linder actually phoned the offending publishers, leading them to run the headline "Max Linder Not Killed".[5] However, others have asserted that he became infected with pneumonia after hiding from a German patrol in icy water for several hours. After being dismissed from his duties, Linder spent the remainder of the war entertaining the troops and making films. It was also during this period that Linder suffered his first serious bout with chronic depression.[4]

Move to the US and career decline 1916–1925

In 1916, Linder was approached by American film producer George K. Spoor, the president of the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company, to make twelve short films for him in the US at a salary of $5,000 a week. Earlier that year, Charlie Chaplin, then the most popular comedian in the world, had left Essanay for more money and independence at Mutual Film and Spoor wanted to replace Chaplin with Max Linder, whose pantomime skills were arguably equally accomplished. Linder was offered a new contract from Charles Pathé, but accepted Spoor's offer and moved to the United States to work for Essanay later that year. Unfortunately his first few American-made "Max" films were unpopular both critically and financially. The first two, Max Comes Across and Max Wants a Divorce were complete failures, but the third film, Max and his Taxi was moderately successful. The financially troubled studio may have been counting on Linder to restore its flagging fortunes and cancelled production of the remaining films on Linder's contract.[4] Max and his Taxi had been shot in Hollywood and while there Linder had developed a close friendship with Charlie Chaplin. They would often attend events such as boxing matches or car races together, and according to writer Jack Spears, "while working on a picture Linder would go next door to Chaplin's home and discuss the day's shooting. The two often sat until dawn, developing and refining the gags. Chaplin's suggestions were invaluable, Linder said."[4]

Linder returned to France in 1917 and opened a movie theater, the Ciné Max Linder. However, due to his depression and anxiety about the still ongoing war, he was unable to continue making films on a regular basis, and was often quoted by journalists about the horrors of the front lines. After the Armistice in 1918, Linder was able to regain his enthusiasm and agreed to make a film with director Raymond Bernard, the feature length The Little Café in 1919. In the film, Linder plays a waiter who suddenly becomes a millionaire, but simultaneously is tricked into a twenty-year contract to be a waiter by the cafe owner. The film made over a million francs in Europe and briefly revived his career, but was financially unsuccessful in the US.[4]

Four years after failing to become a major star in the US, Linder made another attempt at filmmaking in Hollywood and formed his own production company there in 1921. His first film back in the US was Seven Years Bad Luck, considered by some to be his best film. The film contains one of the earliest (though not the first) examples on film of the "human mirror" gag best known in the scene between Groucho and Harpo Marx in Duck Soup twelve years later. Linder next made Be My Wife later that year, but again neither films were able to find a major audience in the US.

Linder then decided to dispense of the "Max" character and try something different for his third (and final) attempt: The Three Must-Get-Theres in 1922. The film is a satire of swashbuckling films made by Douglas Fairbanks and is loosely based on the plot of Alexander Dumas' The Three Musketeers. The film was praised by Fairbanks and Charlie Chaplin, but again failed at the box office. At the films premiere, Linder had said to director Robert Florey "You see, Bob, I sense that I'm no longer funny; I have so many preoccupations that I can no longer concentrate on my film character ... The public is mildly amused by my situations, but this evening where were the explosions of laughter that we hear when Charlie's on the screen?...Make people laugh, its easy to say make people laugh, but I don't feel funny anymore."[4]

With his depression making it difficult for him to work, Linder returned to France in 1922 and shortly afterwards made a semi-serious film: Au Secours! (Help!) for director Abel Gance. The film is essentially a horror film set in a haunted house, with occasional moments of comedy by Linder. The film was released in England in 1924 and was critically praised, however the legal copyright of the film prevented it from being released in France or the US for several years. Linder's last film was The King of the Circus directed by Édouard-Émile Violet (with pre-production collaboration from Jacques Feyder) and filmed in Vienna in 1925. In the film, "Max" joins a circus in order to be closer to the woman that he loves. The film includes such gags as a hungover "Max" waking up in a department store and the film's plot is similar to the Charlie Chaplin film The Circus (1928). In late 1925, Linder was working on pre-production for his next film Barkas le fol, which would never be made.[4]

Marriage and death

As a consequence of his war service, Linder suffered from continuing health problems, including bouts of severe depression. In 1923, he married eighteen-year-old Hélène "Jean" Peters, who came from a wealthy family and with whom he had a daughter, Maud (1924-2017), also known as "Josette".[6]

Linder and his wife may have made a suicide pact. In February 1924, they were both found unconscious at a hotel in Vienna, Austria, though this was explained as an accidental overdose of "sleeping powder."[7] The incident was covered up by the physician reporting it as an accidental overdose of barbiturates. In late October 1925, Max and Hélène reportedly attended a Paris screening of Quo Vadis (in which the main characters, as a reporter put it, "bleed themselves to death"),[8] and died on 1 November in a similar manner. They drank Veronal, injected morphine and slashed their wrists.[4][9]

There is still some question, however, as to whether the deaths were really a result of a suicide pact, or whether Max murdered his much-younger wife or pressured her into killing herself. On 2 November 1925, The New York Times reported that Hélène Linder had told her mother by letter that, "He will kill me." The article also claims that "no one believes she herself opened her veins."[8] Critic Vincent Canby acknowledged in 1988 that "Linder died with his young wife in what has sometimes been described as a suicide pact, and sometimes as a murder-suicide."[10] In addition, Maud Linder reported in her memoir that the head of the workmen at Linder's house in Neuilly overheard Max tell a friend, probably Armand Massard, that he planned to kill his wife along with himself, as he could not bear the thought of her belonging to another after he was gone.[11]

Linder was buried at the Catholique cimetière de Saint-Loubès. His wife is buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.[12]

Legacy

Upon receiving the news of Linder's death, Chaplin is reported to have closed his studio for one day out of respect.[13]

In the ensuing years, Linder was relegated to little more than a footnote in film history until 1963 when a Max Linder compilation film titled Laugh with Max Linder premiered at the Venice Film Festival[14] and was theatrically released. The film was a compilation of Linder's last three films made in Hollywood and its release was supervised by his daughter, Maud Linder.

In 1983, Maud Linder made a documentary film, The Man in the Silk Hat, about Linder's life and career.[4] It was screened out of competition at the 1983 Cannes Film Festival.[15] In 1992, Maud Linder published a book about Linder in France, Max Linder was my father and in 2008 she received the Prix Henri Langlois[16] for her work to promote her father's legacy. In his honor, Lycée Max Linder, a public school in the city of Libourne in the Gironde département near his birthplace was given his name in 1981.[17]

Linder's influence on film comedy and particularly on slapstick films is that the genre shifted from the "knockabout" comedies made by such people as Mack Sennett and André Deed to a more subtle, refined and character driven medium that would later be dominated by Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd and others. Linder's influence on Chaplin is apparent both from Chaplin sometimes borrowing gags or entire plot-lines from Linder's films, as well as from a famous signed photo that Chaplin sent Linder which read: "To Max, the Professor, from his disciple, Charlie Chaplin."[4] Mack Sennett and King Vidor also singled out Linder as a great influence on their directing careers. His high society characterizations as "Max" also influenced such actors as Adolphe Menjou and Raymond Griffith.[4]

In his heyday, Linder had two major rivals in France: Léonce Perret and Charles Prince. Perrett later became a successful director, but his early career included a series of "Léonce" slapstick shorts that were popular but nowhere near the stature of Linder's films. Charles Prince, on the other hand, was gaining popularity during his career and was nearly equal to Linder by the beginning of World War I. Prince's screen persona was "Rigadin", who like "Max" was a bumbling bourgeois socialite who always got into trouble. Both Linder and Prince were employed by Pathé in the early 1910s and they often used the same story lines, sets and directors. Years after both comedians' careers were long over, Linder has received several revivals in interest while Charles Prince remains mostly forgotten.[4]

In popular media

Linder is referenced in Quentin Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds where the owner of a cinema in Nazi occupied Paris in 1944, Shosanna Dreyfus, says that she will be having a Max Linder festival. The relative merits of Linder and Chaplin are then discussed by the German soldier, Frederick Zoller, who argues that Linder is superior to Chaplin while also admitting that Linder never made anything as good as The Kid.

Selected filmography

- 1905 The Legend of Punching

- 1907 The Skater's Debut

- 1909 A Young Lady Killer

- 1909 Max And The Lady Doctor

- 1909 The Cure for Cowardice

- 1910 Max Goes Skiing[18]

- 1910 Max takes a bath

- 1910 Max Linder's Film Debut

- 1911 Max, Victim of Quinine

- 1911 Max and His Mother-in-Law

- 1911 Max Takes Tonics

- 1912 A Farm-House Romance

- 1912 Max Lance La Mode

- 1912 Max and His Dog

- 1912 The Romance of Max

- 1912 Une nuit agitée (An Agitated Night aka:Max in One Exciting Night)

- 1912 A Waterplane Elopement

- 1913 Max's Hat

- 1913 Max Takes a Picture

- 1913 Max Virtuoso

- 1914 Max Does Not Speak English

- 1914 Max and the Jealous Husband

- 1914 The Second of August

- 1914 Max and His Mother-in-Law[19][20]

- 1916 Max and the Clutching Hand

- 1917 Max Comes Across

- 1917 Max Wants a Divorce

- 1917 Max and his Taxi

- 1919 The Little Cafe

- 1921 Seven Years Bad Luck

- 1921 Be My Wife

- 1922 The Three Must-Get-Theres

- 1924 Au Secours!

- 1925 The King of the Circus

- The Porter from Maxim's (1927, screenplay)

References

- Waldekranz, Rune: Filmens Historia - Del 1, p. 208 (P.A. Norstedt & Söners Förlag, Stockholm)

- Hutchinson, Pamela (2019-11-22). "Fame at last – was this the world's first film star?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2019-11-24.

Andrew Shail, senior lecturer in film at Newcastle University, has uncovered what appears to be the first film-star marketing: a poster for a Pathé Frères film featuring [Max] Linder called Le Petit Jeune Homme, released in Europe in September 1909. Whereas Linder had been known on-screen as a first-name-only character called “Max” since 1907’s The Skater’s Debut, this poster uses his full name, and is thus the earliest surviving European evidence of publicity for a regular film performer. [...] 'This makes Linder – as far as we can tell – the first film star anywhere,'

- Mathiesen, Snorre Smàri: "Max Linder: Father of Film Comedy" (Classic Images, March 2012, p. 76)

- Wakeman, John. World Film Directors, Volume 1. The H. W. Wilson Company. 1987. pp. 671-77.

- Paul Merton's Weird and Wonderful World of Early Cinema

- "Parents of suicide dispute over child. French Comedian and Wife Who Killed Themselves in Paris Left Conflicting Wills". Associated Press in the New York Times. 20 January 1935. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

Nine years after the double suicide of Max Linder, celebrated French movie comedian, and his wife the court contest for custody of their daughter, Josette, has been renewed between two embittered families.

- "Max Linder and Wife in Double Suicide. They Drink Veronal, Inject Morphine and Open Veins in Their Arms".

- "Max Linder's Wife Could Not Quit Him. Refused to Heed Her Mother's Pleading, Though She Wrote 'He Will Kill Me.' Both Left Last Letters. "Quo Vadis" Film Is Believed to Have Pointed One Way of Suicide to Star".

- "Max Linder and Wife in Double Suicide. They Drink Veronal, Inject Morphine and Open Veins in Their Arms". New York Times. 1 November 1925. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

Max Linder, one of the earliest film comedians in the world, committed suicide this morning in a death compact with his lovely wife, formerly Miss Peters, a wealthy Paris heiress.

- Vincent Canby (1 April 1988). "Homage to Max Linder, Early French Film Comic". New York Times. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- Linder, Maud (1992). Max Linder Était Mon Père. France: Flammarion. p. 126. ISBN 2-08-066576-6.

- Wilson, Scott (2016). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed. (2 volume set). McFarland. p. 446. ISBN 978-1-4766-2599-7. Retrieved January 25, 2017.

- Max Linder profile, imdb.com; accessed 21 January 2015.

- "Films, TV and people". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 2011-08-04. Retrieved 2012-01-12.

- "VISSZAESOK". Festival de Cannes.

- "借家って何?貸家との違いを紹介します!(What is rented house? We will introduce the difference between the rental!)" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2014-07-14.

- https://www.amaelmaxlinder.fr/la-m%C3%A9moire-du-lyc%C3%A9e/historique/

- Max Fait Du Ski at American Film Institute catalog

- Drew, Bernard A. (2013) Motion Picture Series and Sequels: A Reference Guide Routledge, 490A

- Rège, Philippe (2009) Encyclopedia of French Film Directors Volume 1:646 Scarecrow Press

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Max Linder. |

- Max Linder on IMDb

- Max Linder at Golden Silents

- Photographs and literature

- Institut Max Linder

- "Max Takes a Picture" - 1913 - Max Linder on YouTube

- Max Linder shorts available for free download at archive.org