Genealogy of Jesus

The New Testament provides two accounts of the genealogy of Jesus, one in the Gospel of Matthew and another in the Gospel of Luke.[1] Matthew starts with Abraham, while Luke begins with Adam. The lists are identical between Abraham and David, but differ radically from that point. Matthew has twenty-seven generations from David to Joseph, whereas Luke has forty-two, with almost no overlap between the names on the two lists. Notably, the two accounts also disagree on who Joseph's father was: Matthew says he was Jacob, while Luke says he was Heli.[2]

| Part of a series on |

|

|

Traditional Christian scholars (starting with Africanus and Eusebius[3]) have put forward various theories that seek to explain why the lineages are so different,[4] such as that Matthew's account follows the lineage of Joseph, while Luke's follows the lineage of Mary. Some modern critical scholars like Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan state that both genealogies are inventions, intended to bring the Messianic claims into conformity with Jewish criteria.[5]

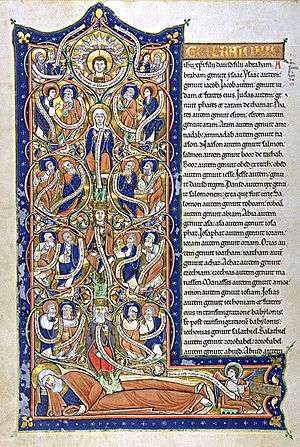

Matthew's genealogy

.jpg)

Matthew 1:1–17 begins the Gospel, "A record of the origin of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham: Abraham begot Isaac, ..." and continues on until "... Jacob begot Joseph, the husband of Mary, of whom was born Jesus, who is called Christ. Thus there were fourteen generations in all from Abraham to David, fourteen from David to the exile to Babylon, and fourteen from the exile to the Christ."

Matthew emphasizes, right from the beginning, Jesus' title Christ—the Greek rendering of the Hebrew title Messiah—meaning anointed, in the sense of an anointed king. Jesus is presented as the long-awaited Messiah, who was expected to be a descendant of King David. Matthew begins by calling Jesus the son of David, indicating his royal origin, and also son of Abraham, indicating that he was an Israelite; both are stock phrases, in which son means descendant, calling to mind the promises God made to David and to Abraham.[6]

Matthew's introductory title (βίβλος γενέσεως, book of generations) has been interpreted in various ways, but most likely is simply a title for the genealogy that follows, echoing the Septuagint use of the same phrase for genealogies.[7]

|

Matthew's genealogy is considerably more complex than Luke's. It is overtly schematic, organized into three sets of fourteen, each of a distinct character:

- The first is rich in annotations, including four mothers and mentioning the brothers of Judah and the brother of Perez.

- The second spans the Davidic royal line, but omits several generations, ending with "Jeconiah and his brothers at the time of the exile to Babylon."

- The last, which appears to span only thirteen generations, connects Joseph to Zerubbabel through a series of otherwise unknown names, remarkably few for such a long period.

The total of 42 generations is achieved only by omitting several names, so the choice of three sets of fourteen seems deliberate. Various explanations have been suggested: fourteen is twice seven, symbolizing perfection and covenant, and is also the gematria (numerical value) of the name David.[6]

The rendering into Greek of Hebrew names in this genealogy is mostly in accord with the Septuagint, but there are a few peculiarities. The form Asaph seems to identify King Asa with the psalmist Asaph. Likewise, some see the form Amos for King Amon as suggesting the prophet Amos, though the Septuagint does have this form. Both may simply be assimilations to more familiar names. More interesting, though, are the unique forms Boes (Boaz, LXX Boos) and Rachab (Rahab, LXX Raab).[8]

Omissions

| Old Testament[9] | Matthew |

|---|---|

David

Solomon

Roboam

Abia

Asaph

Josaphat

Joram

—

—

—

Ozias

Joatham

Achaz

Ezekias

Manasses

Amos

Josias

—

Jechonias

Salathiel

Zorobabel |

Three consecutive kings of Judah are omitted: Ahaziah, Jehoash, and Amaziah. These three kings are seen as especially wicked, from the cursed line of Ahab through his daughter Athaliah to the third and fourth generation.[10] The author could have omitted them to create a second set of fourteen.[11]

Another omitted king is Jehoiakim, the father of Jeconiah, also known as Jehoiachin. In Greek the names are even more similar, both being sometimes called Joachim. When Matthew says, "Josiah begot Jeconiah and his brothers at the time of the exile," he appears to conflate the two, because Jehoiakim, not Jeconiah, had brothers, but the exile was in the time of Jeconiah. While some see this as a mistake, others argue that the omission was once again deliberate, ensuring that the kings after David spanned exactly fourteen generations.[11]

The final group also contains fourteen generations. If Josiah's son was intended as Jehoiakim, then Jeconiah could be counted separately after the exile.[6] Some authors proposed that Matthew's original text had one Joseph as the father of Mary, who then married another man of the same name.[12]

Fourteen generations span the time from Jeconiah, born about 616 BC, to Jesus, born circa 4 BC. The average generation gap would be around forty-four years. However, in the Old Testament, there are even wider gaps between generations.[13] Also, we do not see any instances of papponymic naming patterns, where children are named after their grandparents, which was a common custom throughout this period. This may indicate that Matthew has telescoped this segment by collapsing such repetitions.[14]

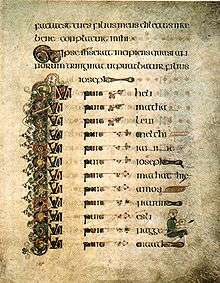

Luke's genealogy

In the Gospel of Luke, the genealogy appears at the beginning of the public life of Jesus. This version is in ascending order from Joseph to Adam.[15] After telling of the baptism of Jesus, Luke 3:23–38 states, "Jesus himself began to be about thirty years of age, being (as was supposed) the son of Joseph, which was [the son] of Heli, ..." (3:23) and continues on until "Adam, which was [the son] of God." (3:38) The Greek text of Luke's Gospel does not use the word "son" in the genealogy after "son of Joseph". Robertson notes that, in the Greek, "Luke has the article tou repeating uiou (Son) except before Joseph".[16]

|

|

This genealogy descends from the Davidic line through Nathan, who is an otherwise little-known son of David, mentioned briefly in the Old Testament.[17]

In the ancestry of David, Luke agrees completely with the Old Testament. Cainan is included between Arphaxad and Shelah, following the Septuagint text (though not included in the Masoretic text followed by most modern Bibles).

Augustine[18] notes that the count of generations in the Book of Luke is 77, a number symbolizing the forgiveness of all sins.[19] This count also agrees with the seventy generations from Enoch[20] set forth in the Book of Enoch, which Luke probably knew.[21] Though Luke never counts the generations as Matthew does, it appears he also followed hebdomadic principle of working in sevens. However, Irenaeus counts only 72 generations from Adam.[22]

The reading "son of Aminadab, son of Aram," from the Old Testament is well attested. The Nestle-Aland critical edition, considered the best authority by most modern scholars, accepts the variant "son of Aminadab, son of Admin, son of Arni,"[23] counting the 76 generations from Adam rather than God.[24]

Luke's qualification "as was supposed" (ἐνομίζετο) avoids stating that Jesus was actually a son of Joseph, since his virgin birth is affirmed in the same gospel. From as early as John of Damascus, the view of "as was supposed of Joseph" regards Luke as calling Jesus a son of Eli—meaning that Heli (Ἠλί, Heli) was the maternal grandfather of Jesus, with Luke tracing the ancestry of Jesus through Mary.[25] Therefore, per Adam Clarke (1817), John Wesley, John Kitto and others the expression "Joseph, [ ] of Heli", without the word "son" being present in the Greek, indicates that "Joseph, of Heli" is to be read "Joseph, [son-in-law] of Heli". There are, however, other interpretations of how this qualification relates to the rest of the genealogy. Some see the remainder as the true genealogy of Joseph, despite the different genealogy given in Matthew.[26]

Comparison of the two genealogies

The following table is a side-by-side comparison of Matthew's and Luke's genealogies. Converging sections are shown with a green background, and diverging sections are shown with a red background.

| Matthew | Luke |

|---|---|

|

Nathan, Mattatha, Menan, Melea,

Eliakim, Jonam, Joseph, Judah,

Simeon, Levi, Matthat, Jorim,

Eliezer, Jose, Er, Elmodam,

Cosam, Addi, Melchi, Neri, | |

|

Salathiel, Zorobabel, | |

|

Abiud, Eliakim,

Azor, Zadok,

Achim, Eliud, Eleazar,

Matthan, Jacob, |

Rhesa, Joannan, Juda, Joseph,

Semei, Mattathias, Maath, Nagge,

Esli, Naum, Amos, Mattathias, Joseph,

Jannai, Melchi, Levi, Matthat, Heli, |

Explanations for divergence

The Church Fathers held that both accounts are true. In his book An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, John Damascene argues that Heli of the tribe of Nathan (the son of David) died childless, and Jacob of the tribe of Solomon, took his wife and raised up seed to his brother and begat Joseph, in accordance with scripture, namely, yibbum (the mitzvah that a man must marry his brother's childless widow); Joseph, therefore, is by nature the son of Jacob, of the line of Solomon, but by law he is the son of Heli of the line of Nathan.[27]

Modern scholarship tends to see the genealogies of Jesus as theological constructs rather than factual history: family pedigrees would not usually have been available for non-priestly families, and the contradictions between the two lists are seen as clear evidence that these were not based on genealogical records. Additionally, the use of titles such as 'Son of God' and 'Son of David' are seen as evidence that they do not come from the earliest Gospel traditions.[28] Raymond E. Brown says the genealogies "tell us nothing certain about his grandparents or his great-grand-parents".[29] Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan contend that both genealogies are inventions to support Messianic claims.[5]

Gundry suggests the series of unknown names in Matthew connecting Joseph's grandfather to Zerubbabel as an outright fabrication, produced by collecting and then modifying various names from 1 Chronicles.[30] Sivertsen sees Luke's as artificially pieced together out of oral traditions. The pre-exilic series Levi, Simeon, Judah, Joseph consists of the names of tribal patriarchs, far more common after the exile than before, while the name Mattathias and its variants begin at least three suspiciously similar segments.[31] Kuhn likewise suggests that the two series Jesus–Mattathias (77–63) and Jesus–Mattatha (49–37) are duplicates.[32]

The contradictions between the lists have been used to question the accuracy of the gospel accounts since ancient times,[33] and several early Christian authors responded to this. Augustine, for example, attempted on several occasions to refute every criticism, not only because the Manichaeans in his day were using the differences to attack Christianity,[34] but also because he himself had seen them in his youth as cause for doubting the veracity of the Gospels.[35] His explanation for the different names given for Joseph's father is that Joseph had a biological father and an adoptive father, and that one of the gospels traces the genealogy through the adoptive father in order to draw parallels between Joseph and Jesus (both having an adoptive father) and as a metaphor for God's relationship with humankind, in the sense that God "adopted" human beings as his children.[36]

One common explanation for the divergence is that Matthew is recording the actual legal genealogy of Jesus through Joseph, according to Jewish custom, whereas Luke, writing for a Gentile audience, gives the actual biological genealogy of Jesus through Mary.[16] This argument is problematic, however, because both trace their genealogy through Joseph. Eusebius of Caesarea, on the other hand, affirmed the interpretation of Africanus that Luke's genealogy is of Joseph (not of Mary), who was the natural son of Jacob, though legally of Eli who was the uterine brother of Jacob.[37]

Levirate marriage

The earliest tradition that explains the divergence of Joseph's lineages involves the law of levirate marriage. A woman whose husband died without issue was bound by law to be married to her husband's brother, and the first-born son of such a so-called levirate marriage was reckoned and registered as the son of the deceased brother (Deuteronomy 25:5 sqq.).[38] Sextus Julius Africanus, in his 3rd-century Epistle to Aristides, reports a tradition that Joseph was born from just such a levirate marriage. According to this report, Joseph's natural father was Jacob son of Matthan, as given in Matthew, while his legal father was Eli son of Melchi (sic), as given in Luke.[39][40]

It has been questioned, however, whether levirate marriages actually occurred among uterine brothers;[41] they are expressly excluded in the Halakhah Beth Hillel but permitted by Shammai.[42] According to Jesuit theologian Anthony Maas, the question proposed to Jesus by the Sadducees in all three Synoptic Gospels[43] regarding a woman with seven levirate husbands suggests that this law was observed at the time of Christ.[38]

Julius Africanus, explaining the origin of Joseph from levirate marriage, makes a mistake:

At the end of the same letter, Africanus adds: "Matthan, a descendant of Solomon, begat Jacob. After the death of Matthan, Melki [must be: Matthat], a descendant of Nathan, begat Heli by the same woman. Therefore, Heli and Jacob must be uterine brothers. Heli died childless; Jacob raised up his seed by begetting Joseph who was his son according to the flesh, and Heli's son according to the Law. So, we can say that Joseph was the son of them both

— (Eusebius of Cesarea. The History of the Church, 1,7)

This error, however, is uncritical:

The explanation offered by Africanus is correct, though he confused Melki with Matthat. The genealogy in Matthew lists births according to the flesh; the one in Luke is according to the Law. It must be added that the levirate links between the two genealogies are found not only at the end, but also in the beginning. This conclusion is obvious because both genealogies intersect in the middle at Zerubbabel, son of Shealtiel (see Mt 1:12–13; Lk 3:27). Nathan was the older brother; Solomon was younger, next in line after him (see 2 Sam 5:14–16; 1 Cron 3:5), therefore he was the first candidate to a levirate marriage (compare Ruth 3–4; Lk 20:27–33). The Old Testament is silent on whether Nathan had children, so we may very well conclude that he had none. Solomon, however, had much capacity for love: «And he had seven hundred wives, princesses, and three hundred concubines» (1 Kings 11:3). So, in theory, he could have married Nathan's widow. If this is so, Mattatha is the son of Solomon according to the flesh and the son of Nathan according to the Law. In light of the above-mentioned circumstances, the differences between the two genealogies no longer present a problem.[44]

Maternal ancestry in Luke

A more straightforward and the most common explanation is that Luke's genealogy is of Mary, with Eli being her father, while Matthew's describes the genealogy of Joseph.[45] This view was advanced as early as John of Damascus (d.749).

Luke's text says that Jesus was "a son, as was supposed, of Joseph, of Eli".[46] The qualification has traditionally been understood as acknowledgment of the virgin birth, but some instead see a parenthetical expression: "a son (as was supposed of Joseph) of Eli."[47] In this interpretation, Jesus is called a son of Eli because Eli was his maternal grandfather, his nearest male ancestor.[45] A variation on this idea is to explain "Joseph son of Eli" as meaning a son-in-law,[48] perhaps even an adoptive heir to Eli through his only daughter Mary.[7] An example of the Old Testament use of such an expression is Jair, who is called "Jair son of Manasseh"[49] but was actually son of Manasseh's granddaughter.[50] In any case, the argument goes, it is natural for the evangelist, acknowledging the unique case of the virgin birth, to give the maternal genealogy of Jesus, while expressing it a bit awkwardly in the traditional patrilinear style.

According to R. A. Torrey, the reason Mary is not implicitly mentioned by name is because the ancient Hebrews never permitted the name of a woman to enter the genealogical tables, but inserted her husband as the son of him who was, in reality, but his father-in-law.[51]

Lightfoot[48] sees confirmation in an obscure passage of the Talmud,[52] which, as he reads it, refers to "Mary daughter of Eli"; however, both the identity of this Mary and the reading are doubtful.[53] Patristic tradition, on the contrary, consistently identifies Mary's father as Joachim. It has been suggested that Eli is short for Eliakim,[45] which in the Old Testament is an alternate name of Jehoiakim,[54] for whom Joachim is named.

The theory neatly accounts for the genealogical divergence. It is consistent with the early tradition ascribing a Davidic ancestry to Mary. It is also consistent with Luke's intimate acquaintance with Mary, in contrast to Matthew's focus on Joseph's perspective. On the other hand, there is no explicit indication whatsoever, either in the Gospel or in any early tradition, that the genealogy is Mary's.

A Jewish tradition relating Mary to Luke's genealogy is recorded in the Doctrina Jacobi (written in 634), in which a Tiberian rabbi mocks the Christian veneration of Mary by recounting her genealogy according to the tradition of the Jews of Tiberias:[55]

Why do Christians extol Mary so highly, calling her nobler than the Cherubim, incomparably greater than the Seraphim, raised above the heavens, purer than the very rays of the sun? For she was a woman, of the race of David, born to Anne her mother and Joachim her father, who was son of Panther. Panther and Melchi were brothers, sons of Levi, of the stock of Nathan, whose father was David of the tribe of Judah.[56]

A century later, John of Damascus and others report the same information, only inserting an extra generation, Barpanther (Aramaic for son of Panther, thus indicating a misunderstood Aramaic source).[57] A certain prince Andronicus later found the same polemic in a book belonging to a rabbi named Elijah:[58]

After John of Damascus the claim that Luke gives Mary's genealogy is mentioned in a single extant Western medieval text, in which pseudo-Hilary cites it as an opinion held by many, though not himself.[59] This claim was revived by Annius of Viterbo in 1498[60] and quickly grew in popularity.

Modern scholars discount this approach: Raymond E. Brown called it a "pious deduction"; and Joachim Gnilka "the desperation of embarrassment".[61]

Jewish law is relevant to these matters. It does not accept maternal ancestry as applying to lineage claims, which go through the father alone.

Maternal ancestry in Matthew

A minority view holds that while Luke gives the genealogy of Joseph, Matthew gives the genealogy of Mary. A few ancient authorities seem to offer this interpretation.[62] Although the Greek text as it stands is plainly against it, it has been proposed that in the original text Matthew had one Joseph as Mary's father and another as her husband. This neatly explains not only why Matthew's genealogy differs from Luke's, but also why Matthew counts fourteen generations rather than thirteen. Blair sees the various extant versions as the predictable result of copyists repeatedly attempting to correct an apparent mistake.[12] Others, including Victor Paul Wierwille,[63] argue that here the Aramaic original of Matthew used the word gowra (which could mean father), which, in the absence of vowel markings, was read by the Greek translator as gura (husband).[64] In any case, an early understanding that Matthew traced Mary's genealogy would explain why the contradiction between Matthew and Luke apparently escaped notice until the 3rd century.

Lukan version of Levirate marriage theory

Although most accounts ascribing the Luke genealogy to Mary's line do not include a levirate marriage this is added by the above sources. Each of these texts then goes on to describe, just as in Julius Africanus (but omitting the name of Estha), how Melchi was related to Joseph through a levirate marriage.

| Family tree | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bede assumed that Julius Africanus was mistaken and corrected Melchi to Matthat.[65] Since papponymics were common in this period,[31] however, it would not be surprising if Matthat were also named Melchi after his grandfather.

Panther

Controversy has surrounded the name Panther, mentioned above, because of a charge that Jesus' father was a soldier named Pantera. Celsus mentions this in his writing, The True Word, where he is quoted by Origen in Book 1:32. "But let us now return to where the Jew is introduced, speaking of the mother of Jesus, and saying that "when she was pregnant she was turned out of doors by the carpenter to whom she had been betrothed, as having been guilty of adultery, and that she bore a child to a certain soldier named Panthera."[66][67] Epiphanius, in refutation of Celsus, writes that Joseph and Cleopas were sons of "Jacob, surnamed Panther."[68]

Two Talmudic-era texts referring to Jesus as the son of Pantera (Pandera) are Tosefta Hullin 2:22f: "Jacob… came to heal him in the name of Jesus son of Pantera" and Qohelet Rabbah 1:8(3): "Jacob… came to heal him in the name of Jesus son of Pandera" and some editions of the Jerusalem Talmud also specifically name Jesus as the son of Pandera:[69] Jerusalem Abodah Zarah 2:2/7: "someone… whispered to him in the name of Jesus son of Pandera"; Jerusalem Shabboth 14:4/8: "someone… whispered to him in the name of Jesus son of Pandera"; Jerusalem Abodah Zarah 2:2/12: "Jacob… came to heal him. He said to him: we will speak to you in the name of Jesus son of Pandera"; Jerusalem Shabboth 14:4/13: "Jacob… came in the name of Jesus Pandera to heal him". Because some editions of the Jerusalem Talmud do not contain the name Jesus in these passages the association is disputed.

Legal inheritance

One of the traditional explanations is that Matthew traces not a genealogy in the modern biological sense, but a record of legal inheritance showing the succession of Jesus in the royal line.

According to this theory, Matthew's immediate goal is therefore not David, but Jeconiah, and in his final group of fourteen, he may freely jump to a maternal grandfather, skip generations, or perhaps even follow an adoptive lineage in order to get there.[70] Attempts have been made to reconstruct Matthew's route, from the seminal work of Lord Hervey[71] to Masson's recent work,[72] but all are necessarily highly speculative.

As a starting point, one of Joseph's two fathers could be by simple adoption, as Augustine suggests, or more likely the special adoption by a father-in-law with no sons, or could be a maternal grandfather.[73] On the other hand, the resemblance between Matthan and Matthat suggests they are the same man (in which case Jacob and Eli are either identical or full brothers involved in a levirate marriage), and Matthew's departure from Luke at that point can only be to follow legal line of inheritance, perhaps through a maternal grandfather. Such reasoning could further explain what has happened with Zerubbabel and Shealtiel.[71] A key difficulty with these explanations, however, is that there is no adoption in Jewish law, which of course is the relevant law tradition even according to Jesus (Matt. 23:1–3), not the Roman law tradition. If Joseph is not the biological father, his lineage does not apply to Jesus, and there is no provision available within Jewish law for this to be altered. One's natural father is always one's father. Nor is inheritance of lineage claims even possible through one's mother, in Jewish law.[74]

Zerubbabel son of Shealtiel

The genealogies in Luke and Matthew appear to briefly converge at Zerubbabel son of Shealtiel, though they differ both above Shealtiel and below Zerubbabel. This is also the point where Matthew departs from the Old Testament record.

In the Old Testament, Zerubbabel was a hero who led the Jews back from Babylon about 520 BC, governed Judah, and rebuilt the temple. Several times he is called a son of Shealtiel.[75] He appears once in the genealogies in the Book of Chronicles,[76] where his descendants are traced for several generations, but the passage has a number of difficulties.[77] While the Septuagint text here gives his father as Shealtiel, the Masoretic text instead substitutes Shealtiel's brother Pedaiah—both sons of King Jeconiah, according to the passage. Some, accepting the Masoretic reading, suppose that Pedaiah begot a son for Shealtiel through a levirate marriage, but most scholars now accept the Septuagint reading as original, in agreement with Matthew and all other accounts.[78]

The appearance of Zerubbabel and Shealtiel in Luke may be no more than a coincidence of names (Zerubbabel, at least, is a very common Babylonian name[79]). Shealtiel is given a completely different ancestry, and Zerubbabel a different son. Furthermore, interpolation between known dates would put the birth of Luke's Shealtiel at the very time when the celebrated Zerubbabel led the Jews back from Babylon. Thus, it is likely that Luke's Shealtiel and Zerubbabel were distinct from, and perhaps even named after, Matthew's.[45]

If they are the same, as many insist, then the question arises of how Shealtiel, like Joseph, could have two fathers. Yet another complex levirate marriage has often been invoked.[45] Richard Bauckham, however, argues for the authenticity of Luke alone. In this view, the genealogy in Chronicles is a late addition grafting Zerubbabel onto the lineage of his predecessors, and Matthew has simply followed the royal succession. In fact, Bauckham says, Zerubbabel's legitimacy hinged on descending from David through Nathan rather than through the prophetically cursed ruling line.[21]

The name Rhesa, given in Luke as the son of Zerubbabel, is usually seen as the Aramaic word rēʾšāʾ, meaning head or prince. It might well befit a son of Zerubbabel, but some see the name as a misplaced title of Zerubbabel himself.[21] If so, the next generation in Luke, Joanan, might be Hananiah in Chronicles. Subsequent names in Luke, as well as Matthew's next name Abiud, cannot be identified in Chronicles on more than a speculative basis.

Fulfillment of prophecy

By the time of Jesus, it was already commonly understood that several prophecies in the Old Testament promised a Messiah descended from King David.[80][81] Thus, in tracing the Davidic ancestry of Jesus, the Gospels aim to show that these messianic prophecies are fulfilled in him.

The prophecy of Nathan[82]—understood as foretelling a son of God who would inherit the throne of his ancestor David and reign forever—is quoted in Hebrews[83] and strongly alluded to in Luke's account of the Annunciation.[84] Likewise, the Psalms[85] record God's promise to establish the seed of David on his throne forever, while Isaiah[86] and Jeremiah[87] speak of the coming reign of a righteous king of the house of David.

David's ancestors are also understood as progenitors of the Messiah in several prophecies.[80] Isaiah's description of the branch or root of Jesse[88] is cited twice by Paul as a promise of the Christ.[89]

More controversial are the prophecies on the Messiah's relation, or lack thereof, to certain of David's descendants:

- God promised to establish the throne of King Solomon over Israel forever,[90] but the promise was contingent upon obeying God's commandments.[91] Solomon's failure to do so is explicitly cited as a reason for the subsequent division of his kingdom.[92]

- Against King Jehoiakim, Jeremiah prophesied, "He shall have no one to sit on the throne of David,"[93] and against his son King Jeconiah, "Write this man childless, a man who will not prosper in his days; for no man of his seed will prosper, sitting on the throne of David or ruling again in Judah."[94] Some see this prophecy as permanently disqualifying Jeconiah from the ancestry of the Messiah (though not necessarily of Joseph).[95] More likely, the curse was limited to Jeconiah's lifetime, and even then, rabbinical tradition has it that Jeconiah repented in exile and the curse was lifted.[96] Additionally, the Old Testament recounts that none of the punishments listed in the curse actually came to pass.[97]

- To Zerubbabel, God declares through Haggai, "I will make you like my signet ring," in clear reversal of the prophecy against his grandfather Jeconiah, "though you were a signet ring on my right hand, yet I would pull you off."[98] Zerubbabel ruled as governor, though not as king, and has been regarded by many as a suitable and likely progenitor of the Messiah.

The promise to Solomon and Jeconiah's curse, if applicable, argue against Matthew. Yet evidently Matthew didn't find his respective genealogy incompatible with these prophecies.

Matthew also presents the virgin birth of Jesus as fulfillment of Isaiah 7:14, which he quotes.[99] Matthew apparently quotes the ancient Septuagint translation of the verse, which renders the Hebrew word "almah" as "virgin" in Greek.

Desposyni

Desposyni (Greek δεσπόσυνοι, desposynoi, "those of the master") is a term used uniquely by Sextus Julius Africanus[39] to refer to the relatives of Jesus. The Gospels mention four brothers of Jesus – James, Joses, Simon, and Jude[100] – and unnamed sisters.

Epiphanius of Salamis relates that the four brothers and the unnamed sisters that he names as Mary and Salome[101] (or Anna and Salome)[102] were children of Joseph by a previous marriage. These and their descendants were prominent in the early Church down to the 2nd century.[103] Muslim authors extend family members to the 7th century.

Since ancient times, it has been debated precisely how these siblings were related to Jesus, or rather to Joseph and Mary, with her perpetual virginity at issue. There are three principal views on who these siblings were, named for their respective proponents:[103]

- The Helvidian view—subsequent children of Joseph and Mary.

- The Epiphanian view—children of Joseph by a previous marriage.

- The Hieronymian view—first cousins of Jesus, and that Joseph was himself a virgin.[104]

There is no suggestion in ancient sources that Jesus himself had any physical children, but a claim has been popularized in recent decades that a bloodline of Jesus, through Mary Magdalene, has survived and subsequently recorded in the[105] book The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail.

Women mentioned

Matthew inserts four women into the long list of men. The women are included early in the genealogy—Tamar, Rachab, Ruth, and "the wife of Uriah" (Bathsheba). Why Matthew chose to include these particular women, while passing over others such as the matriarchs Sarah, Rebecca, and Leah, has been much discussed.

There may be a common thread among these four women, to which Matthew wishes to draw attention. He sees God working through Tamar's seduction of her father-in-law, through the collusion of Rahab the harlot with Joshua's spies, through Ruth the Moabite's unexpected marriage with Boaz, and through David and Bathsheba's adultery.[106]

The NIV Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible suggests that the common thread between all of these women is that they have associations with Gentiles.[107] Rahab was a prostitute in Canaan, Bathsheba was married to a Hittite, Ruth resided in Moab, and Tamar had a name of Hebrew origin. The women's nationalities are not necessarily mentioned. The suggestion is that Matthew may be preparing the reader for the inclusion of the Gentiles in Christ's mission. Others point out an apparent element of sinfulness: Rahab was a prostitute, Tamar posed as a prostitute to seduce Judah, Bathsheba was an adulteress, and Ruth is sometimes seen as seducing Boaz—thus Matthew emphasizes God's grace in response to sin. Still others point out their unusual, even scandalous, unions—preparing the reader for what will be said about Mary. None of these explanations, however, adequately befits all four women.[108]

Nolland suggests simply that these were all the known women attached to David's genealogy in the Book of Ruth.[6]

The conclusion of the genealogy proper is also unusual: having traced the ancestry of Joseph, Matthew identifies him not as the father of Jesus, but as the husband of Mary. The Greek text is explicit in making Jesus born to Mary, rather than to Joseph. This careful wording is to affirm the virgin birth, which Matthew proceeds to discuss, stating that Jesus was begotten not by Joseph but by God.

Mary's kinship with Elizabeth

Luke states that Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist, was a "relative" (Greek syggenēs, συγγενής) of Mary, and that Elizabeth was descended from Aaron, of the tribe of Levi.[109] Whether she was an aunt, a cousin, or a more distant relation cannot be determined from the word. Some, such as Gregory Nazianzen, have inferred from this that Mary herself was also a Levite descended from Aaron, and thus kingly and priestly lineages were united in Jesus.[110] Others, such as Thomas Aquinas, have argued that the relationship was on the maternal side; that Mary's father was from Judah, Mary's mother from Levi.[111] Modern scholars like Raymond Brown (1973) and Géza Vermes (2005) suggest that the relationship between Mary and Elizabeth is simply an invention of Luke.[112]

Virgin birth

These two Gospels declare that Jesus was begotten not by Joseph, but by the power of the Holy Spirit while Mary was still a virgin, in fulfillment of prophecy. Thus, in mainstream Christianity, Jesus is regarded as being literally the "only begotten son" of God, while Joseph is regarded as his adoptive father.

Matthew immediately follows the genealogy of Jesus with: "This is how the birth of Jesus Christ came about: His mother Mary was pledged to be married to Joseph, but before they came together, she was found to be with child through the Holy Spirit".[113]

Likewise, Luke tells of the Annunciation: "How will this be," Mary asked the angel, "since I am a virgin?" The angel answered, "The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you. So the holy one to be born will be called the Son of God."[114]

The question then arises, why do both gospels seem to trace the genealogy of Jesus through Joseph, when they deny that he is his biological father? Augustine considers it a sufficient answer that Joseph was the father of Jesus by adoption, his legal father, through whom he could rightfully claim descent from David.[115]

Tertullian, on the other hand, argues that Jesus must have descended from David by blood through his mother Mary.[116] He sees Biblical support in Paul's statement that Jesus was "born of a descendant of David according to the flesh".[117] Affirmations of Mary's Davidic ancestry are found early and often.[118]

The Ebionites, a sect who denied the virgin birth, used a gospel which, according to Epiphanius, was a recension of Matthew that omitted the genealogy and infancy narrative.[119] These differences reflect the Ebionites' awareness of Jewish law (halakhah) relating to lineage inheritance, adoption, and the status of ancestry claims through the mother.

Islam

The Qurʼan upholds the virgin birth of Jesus (ʻĪsā)[120] and thus considers his genealogy only through Mary (Maryam), without mentioning Joseph.

Mary is very highly regarded in the Qurʼan, the nineteenth sura being named for her. She is called a daughter of ʻImrān,[121] whose family is the subject of the third sura. The same Mary (Maryam) is also called a sister of Aaron (Hārūn) in one place,[122] and although this is often seen as an anachronistic conflation with the Old Testament Miriam (having the same name), who was sister to Aaron (Hārūn) and daughter to Amram (ʻImrān), the phrase is probably not to be understood literally.[123]

According to Muslim Scholar Sheikh Ibn Al-Feasy Al-Hanbali, the Quran used "Sister of Aaron" and "Daughter of Amram" for several reasons. One of those is the "relative calling" or laqb that is always used in Arabic literature. Ahmad bin Muhammad bin Hanbal Abu 'Abd Allah al-Shaybani, for instance, is prevalently called "Ibn Hanbal" instead of "Ibn Mohammad". Or, Muhammad bin Idris asy-Syafi`i is always called "Imam Al-Shafi'i" instead of "Imam Idris" or "Imam Muhammad". This is how the Arabs refer to famous persons in their daily life. The same applies here; Sister of Aaron refers to "daughter of Aaron's siblings'", and daughter of Amram refers to "direct lineage of Amram" (Amram's descendants). This means that Mary was from the line of Amram, but not of Aaron's generation.

See also

Notes

- Matthew 1:1–16; Luke 3:23–38

- Matthew 1:16; Luke 3:23

- Eusebius Pamphilius, Church history, Life of Constantine §VII.

- R. T. France, The Gospel According to Matthew: An Introduction and Commentary (Eerdmans, 1985) pages 71–72.

- Marcus J. Borg, John Dominic Crossan, The First Christmas (HarperCollins, 2009) page 95.

- Nolland, John (2005), The Gospel of Matthew: a commentary on the Greek text, Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans, pp. 65–87, ISBN 978-0-8028-2389-2

- Nolland, John (2005), The Gospel of Matthew: a commentary on the Greek text, Grand Rapids: W. B. Eerdmans, p. 70, ISBN 978-0-8028-2389-2, considers this harmonization "the most attractive."

- Bauckham, Richard (1995), "Tamar's Ancestry and Rahab's Marriage: Two Problems in the Matthean Genealogy", Novum Testamentum, 37 (4): 313–329, doi:10.1163/1568536952663168.

- 1Chronicles 3:4–19.

- 1Kings 21:21–29; cf. Exodus 20:5, Deuteronomy 29:20.

- Nolland, John (1997), "Jechoniah and His Brothers" (PDF), Bulletin for Biblical Research, Biblical studies, 7: 169–78.

- Blair, Harold A. (1964), "Matthew 1,16 and the Matthaean Genealogy", Studia Evangelica, 2: 149–54.

- For example, Ezra's genealogy in Ezra 7:1–5 (cf. 1Chronicles 6:3–14).

- Albright, William F. & Mann, C.S. (1971), Matthew: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, The Anchor Bible, 26, New York: Doubleday & Co, ISBN 978-0-385-08658-5.

- Maas, Anthony. "Genealogy of Christ" The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 9 October 2013

- Robertson, A.T. "Commentary on Luke 3:23". "Robertson's Word Pictures of the New Testament". Broadman Press 1932,33, Renewal 1960.

- 1Chronicles 3:5; but also see Zechariah 12:12.

- Augustine of Hippo (c. 400), De consensu evangelistarum (On the Harmony of the Gospels), pp. 2.4.12–13

- Matthew 18:21–22; cf. Genesis 4:24.

- 1 Enoch 10:11–12.

- Bauckham, Richard (2004), Jude and the Relatives of Jesus in the Early Church, London: T & T Clark International, pp. 315–373, ISBN 978-0-567-08297-8

- Irenaeus, Adversus haereses ("Against Heresies"), p. 3.22.3

- Willker, Wieland (2009), A Textual Commentary on the Greek Gospels (PDF), vol. 3: Luke (6th ed.), p. TVU 39, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009, retrieved 25 March 2009. Willker details the textual evidence underlying the NA27 reading.

- "Faced with a bewildering variety of readings, the Committee adopted what seems to be the least unsatisfactory form of text, a reading that was current in the Alexandrian church at an early period," explains Metzger, Bruce Manning (1971), A textual commentary on the Greek New Testament (2nd ed.), United Bible Societies, p. 136, ISBN 3-438-06010-8

- Schaff, Philip (1882), The Gospel According to Matthew, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 4–5, ISBN 0-8370-9740-1

- Farrar, F.W. (1892), The Gospel According to St. Luke, Cambridge, pp. 369–375

- Damascene, John. "BOOK IV CHAPTER XIV -> Concerning our Lord's genealogy and concerning the holy Mother of God".. Quote: "Born then of the line of Nathan, the son of David, Levi begat Melchi(2) and Panther: Panther begat Barpanther, so called. This Barpanther begat Joachim: Joachim begat the holy Mother of God(3)(4). And of the line of Solomon, the son of David, Mathan had a wife(5) of whom he begat Jacob. Now on the death of Mathan, Melchi, of the tribe of Nathan, the son of Levi and brother of Panther, married the wife of Mathan, Jacob's mother, of whom he begat Heli. Therefore Jacob and Hell became brothers on tile mother's side, Jacob being of the tribe of Solomon and Heli of the tribe of Nathan. Then Heli of the tribe of Nathan died childless, and Jacob his brother, of the tribe of Solomon, took his wife and raised up seed to his brother and begat Joseph. Joseph, therefore, is by nature the son of Jacob, of the line of Solomon, but by law he is the son of Heli of the line of Nathan."

- Marshall D. Johnson The Purpose of the Biblical Genealogies with Special Reference to the Setting of the Genealogies of Jesus (Wipf and Stock, 2002) page

- Raymond E. Brown, The Birth of the Messiah (Doubleday, 1977), page 94.

- Gundry, Robert H. (1982), Matthew: A Commentary on his Literary and Theological Art, Grand Rapids: W. B. Eerdmans, ISBN 978-0-8028-3549-9

- Sivertsen, Barbara (2005), "New testament genealogies and the families of Mary and Joseph", Biblical Theology Bulletin, 35 (2): 43–50, doi:10.1177/01461079050350020201.

- As summarized in Marshall, I. Howard (1978), The Gospel of Luke: A Commentary on the Greek Text, Grand Rapids: W. B. Eerdmans, p. 159, ISBN 0-8028-3512-0

- A famous example is the anti-Christian polemic of the Roman Emperor Julian the Apostate, Against the Galileans.

- Augustine of Hippo, Contra Faustum (Reply to Faustus, c. 400)

- Augustine of Hippo, Sermon 1, p. 6

- Augustine of Hippo, Contra Faustum (Reply to Faustus, c. 400), p. 3

- Joel B. Green; Scot McKnight; I. Howard Marshall, eds. (1992), Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels: A Compendium of Contemporary Biblical Scholarship, InterVarsity Press, pp. 254–259, ISBN 0-8308-1777-8

- Maas, Anthony. "Genealogy (in the Bible)." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 9 Oct. 2013

- Sextus Julius Africanus, Epistula ad Aristidem (Epistle to Aristides)

- Johnson, however, gives a text with much the same passage, to which, he suggests, Julius Africanus may have been responding: Johnson, Marshall D. (1988), The purpose of the Biblical genealogies (2nd ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 273, ISBN 978-0-521-35644-2

- Mussies, Gerard (1986), "Parallels to Matthew's Version of the Pedigree of Jesus", Novum Testamentum, 28 (1): 32–47 [41], doi:10.1163/156853686X00075, JSTOR 1560666.

-

- Matthew 22:24; Mark 12:19; Luke 20:28

- Sterkh V. "Answers for a Jew"

- Maas, Anthony (1913), , in Herbermann, Charles (ed.), Catholic Encyclopedia, New York: Robert Appleton Company

- Luke 3:23.

- Aquinas, Thomas, Summa Theologica, p. IIIa, q.31, a.3, Reply to Objection 2, offers this interpretation, that Luke calls Jesus a son of Eli, without making the leap to explain why.

- Lightfoot, John (1663), Horæ Hebraicæ et Talmudicæ, 3 (published 1859), p. 55

- Numbers 32:41; Deuteronomy 3:14; 1Kings 4:13.

- 1Chronicles 2:21–23;1Chronicles 7:14.

- Torrey, R. A. "Commentary on Luke 3". "The Treasury of Scriptural Knowledge", 1880.

- j. Hagigah 77d.

- Mary's Genealogy & the Talmud, archived from the original on 23 March 2009, retrieved 25 March 2009

- 2Chronicles 36:4.

- Doctrina Jacobi, p. 1.42 (PO 40.67–68). }}

- Translation from Williams, A. Lukyn (1935), Adversus Judaeos: a bird's-eye view of Christian apologiae until the Renaissance, Cambridge University Press, pp. 184–185, OCLC 747771

- John of Damascus, De fide orthodoxa (An Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith), p. 4.14. Andrew of Crete, Oration 6 (On the Circumcision of Our Lord) (PG 97.916). Epiphanius the Monk, Sermo de vita sanctissimae deiparae (Life of Mary) (PG 120.189). The last apparently draws from a lost work of Cyril of Alexandria, perhaps via Hippolytus of Thebes.

- Andronicus, Dialogus contra Iudaeos, p. 38 (PG 113.859–860). The author of this dialogue is now believed to be a nephew of Michael VIII living about 1310.

- Pseudo-Hilary, Tractate 1, apud Angelo Mai, ed. (1852), Nova patrum bibliotheca, 1, pp. 477–478Multi volunt, generationem, quam enumerat Matthaeus, deputari Ioseph, et generationem quam enumerat Lucas, deputari Mariae, ut quia caput mulieris vir dicitur, viro etiam eiusdem generatio nuncupetur. Sed hoc regulae non-convenit, vel quaestioni quae est superius: id est, ubi generationum ratio demonstrator, verissime solutum est.

- Annius of Viterbo (1498), Antiquitatum Variarum. In this notorious forgery, Joachim is identified as Eli in a passage ascribed to Philo.

- Cited in Frederick Dale Bruner, Matthew: The Christbook, Matthew 1–12 (Eerdmans, 2004), page 21-22. See also Larry Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ (Eerdmans, 2003), page 273.

- Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, p. 21,

And in the Gospel according to Matthew, the genealogy which begins with Abraham is continued down to Mary the mother of the Lord.

Victorinus of Pettau, In Apocalypsin (Commentary on the Apocalypse), pp. 4.7–10,Matthew strives to declare to us the genealogy of Mary, from whom Christ took flesh.

But already the possibility is excluded by Irenaeus, Adversus haereses (Against Heresies), p. 3.21.9 - Victor Paul Wierwille, Jesus Christ Our Promised Seed, American Christian Press, New Knoxville, OH, 2006, pages 113–132.

- Roth, Andrew Gabriel (2003), Proofs of Peshitta Originality in the Gospel According to Matthew & the Gowra Scenario: Exploding the Myth of a Flawed Genealogy (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2009, retrieved 25 April 2009

- Bede, In Lucae evangelium expositio (On the Gospel of Luke), p. 3

- Origen. "Against Celsus". Archived from the original on 27 April 2006.

- Origen. "Contra Celsum" [Reply to Celsus]. Christian classics ethereal library. 1.32.

- of Salamis, Epiphanius; Williams, Frank (2013). The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis: De fide. Books II and III Sect 78:7,5. Brill. p. 620. ISBN 978-900422841-2.

- Schaefer, pp. 52–62, 133–41.

- Johnson, Marshall D. (1988), The purpose of the Biblical genealogies (2nd ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 142, ISBN 978-0-521-35644-2

- Hervey, Arthur Charles (1853), The Genealogies of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ

- Masson, Jacques (1982), Jesus, fils de David, dans les généalogies de saint Mathieu et de saint Luc, Paris: Téqui, ISBN 2-85244-511-5

- Augustine of Hippo, Sermon 1, pp. 27–29

- See, on this, the articles "Adoption" by Lewis Dembitz and Kaufmann Kohler in The Jewish Encyclopaedia (1906), available online at: http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/852-adoption, and "Adoption" by Jeffrey H. Tigay and Ben-Zion (Benno) Schereschewsky in the Encyclopaedia Judaica (1st ed. 1972; the entry is reproduced again in the 2nd ed.), Vol. 2, col. 298–303. Lineage cannot be artificially transferred; one's natural parents are always one's parents. Guardianship, however, conveys most other rights and duties. Schereschewsky summarizes, col. 301: "Adoption is not known as a legal institution in Jewish law. According to halakhah [Jewish law] the personal status of parent and child is based on the natural family relationship only and there is no recognized way of creating this status artificially by a legal act or fiction. However, Jewish law does provide for consequences essentially similar to those caused by adoption to be created by legal means. These consequences are the right and obligation of a person to assume responsibility for (a) a child's physical and mental welfare and (b) his financial position, including matters of inheritance and maintenance." The "matters of inheritance" being referred to here is provision for inheritance of property, not lineage ancestry. Also relevant is the same Encyclopaedia's article on "Apotropos," i.e., guardianship, reproduced at http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0002_0_01191.html, and the introduction to these two articles helpfully summarizing the main points, by the editors of the Jewish Virtual Library, "Issues in Jewish Ethics: Adoption," at http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Judaism/adoption.html Also see the series of five articles or chapters by R. Michael J. Broyde, "The Establishment of Maternity and Paternity in Jewish and American Law," at the Jewish Law website http://www.jlaw.com/Articles/maternity1.html, in particular the opening comments to the first chapter and the whole discussion in its chapter "IV. Adoption and Establishing Parental Status," at http://www.jlaw.com/Articles/maternity4.html. For further discussion, see this article's "Talk" page.

- Ezra 3:2,8;5:2; Nehemiah 12:1; Haggai 1:1,12,14.

- 1Chronicles 3:17–24

- VanderKam, James C. (2004), From Joshua to Caiaphas: High Priests after the Exile, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, pp. 104–106, ISBN 978-0-8006-2617-4

- Japhet, Sara (1993), I & II Chronicles: A Commentary, Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press, p. 100, ISBN 978-0-664-22641-1

- Finkelstein, Louis (1970), The Jews: Their History (4th ed.), Schocken Books, p. 51, ISBN 0-313-21242-2

- Juel, Donald (1992), Messianic Exegesis: Christological Interpretation of the Old Testament in Early Christianity, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, pp. 59–88, ISBN 978-0-8006-2707-2

- See John 7:42; Matthew 22:41-42.

- 2Samuel 7:12–16.

- Hebrews 1:5.

- Luke 1:32–35.

- Psalms 89:3–4; Psalms 132:11.

- Isaiah 16:5.

- Jeremiah 23:5–6.

- Isaiah 11:1–10.

- Acts 13:23; Romans 15:12.

- 1Chronicles 22:9–10

- 1Chronicles 28:6–7; 2Chronicles 7:17–18; 1Kings 9:4–5.

- 1Kings 11:4–11.

- Jeremiah 36:30

- Jeremiah 22:24–30.

- For example, Irenaeus, Adversus haereses ("Against Heresies"), p. 3.21.9j

- Johnson, Marshall D. (1988), The purpose of the Biblical genealogies (2nd ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 184, ISBN 978-0-521-35644-2

- "The Problem of the Curse on Jeconiah in Relation to the Genealogy of Jesus - Jews for Jesus". Jews for Jesus. 1 January 2005.

- Haggai 2:23 (cf. Jeremiah 22:24).

- Matthew 1:22–23, citing Isaiah 7:14.

- Matthew 13:55; Mark 6:3.

- Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion, pp. 78.8.1, 78.9.6

- College, St. Epiphanius of Cyprus ; translated by Young Richard Kim, Calvin (2014). Ancoratus 60:1. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-8132-2591-3. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Bauckham, Richard (2004), Jude and the Relatives of Jesus in the Early Church, London: T & T Clark International, pp. 5–31, ISBN 978-0-567-08297-8

- Tobin, Paul (2003), Rejection of Pascal's Wager: James, The Brother of Jesus

- Bradley, Ed (30 April 2006), Langley, Jeanne (ed.), "The Secret of the Priory of Sion", 60 Minutes, CBS News, CBS Worldwide Inc.

- Maloney C.M., Robert P. "The Genealogy of Jesus: Shadows and lights in his past", America, December 17, 2007

- NIV cultural backgrounds study Bible : bringing to life the ancient world of Scripture. Walton, John H., 1952–, Keener, Craig S., 1960–. Grand Rapids. 2016. ISBN 9780310431589. OCLC 958938689.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Hutchinson, John C. (2001), "Women, Gentiles, and the Messianic Mission in Matthew's Genealogy", Bibliotheca Sacra, 158: 152–164

- Luke 1:5,36.

- For example, Carmen 18

- Aquinas, Thomas, Summa Theologica, pp. IIIa, q.31, a.2

- Brown, Raymond E. (1973), The Virginal Conception and Bodily Resurrection of Jesus, Paulist Press, p. 54, ISBN 0-8091-1768-1, describes the relationship, not mentioned in the other Gospels, as "of dubious historicity." Vermes, Géza (2006), The Nativity, Random House, p. 143, ISBN 978-0-385-52241-0, calls it "artificial and undoubtedly Luke's creation."

- Matthew 1:18.

- Luke 1:34–35.

- Augustine of Hippo, De consensu evangelistarum (On the Harmony of the Gospels), pp. 2.1.2–4; Augustine of Hippo, Sermon 1, pp. 16–21

- Tertullian, De carne Christi ("On the Flesh of Christ"), pp. 20–22

- Romans 1:3.

- Ignatius of Antioch, Epistle to the Ephesians, p. 18. Martyr, Justin, Dialogus cum Tryphone Judaeo (Dialogue with Trypho), p. 100

- Epiphanius of Salamis, Panarion, p. 30.14

- Quran 19:20–22.

- Quran 66:12;Quran 3:35–36.

- Quran 19:28.

- Thomas Patrick Hughes, ed. (1995), "ʻImrān", A Dictionary of Islam, New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, ISBN 978-81-206-0672-2

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article Genealogy of Christ. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Genealogy of Jesus Christ. |

Genealogy of Jesus | ||

| Preceded by Pre-existence of Christ |

New Testament Events |

Succeeded by Birth of John the Baptist |