Marrella

Marrella is an extinct genus of arthropod known from the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia. It is the most common animal represented in the Burgess Shale.

| Marrella splendens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil Marrella | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Marrellidae Walcott, 1912 |

| Genus: | Marrella Walcott, 1912 |

| Species: | M. splendens |

| Binomial name | |

| Marrella splendens Walcott, 1912 | |

History

Marrella was the first fossil collected by Charles Doolittle Walcott from the Burgess Shale, in 1909.[1] Walcott described Marrella informally as a "lace crab" and described it more formally as an odd trilobite. It was later reassigned to the now defunct class Trilobitoidea in the Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. In 1971, Whittington undertook a thorough redescription of the animal and, on the basis of its legs, gills and head appendages, concluded that it was neither a trilobite, nor a chelicerate, nor a crustacean.[2]

Marrella is one of several unique arthropod-like organisms found in the Burgess Shale. Other examples are Opabinia and Yohoia. The unusual and varied characteristics of these creatures were startling at the time of discovery. The fossils, when described, helped to demonstrate that the soft-bodied Burgess fauna was more complex and diverse than had previously been anticipated.[3]

Morphology

Marrella itself is a small animal, 2 cm or less in length. The head shield has two pairs of long rearward spikes. On the underside of the head are two pairs of antennae, one long and sweeping, the second shorter and stouter. Marrella has a body composed of 24–26 body segments, each with a pair of branched appendages. The lower branch of each appendage is a leg for walking, while the upper branch is a long, feathery gill. There is a tiny, button-like telson at the end of the thorax. It is unclear how the unmineralized head and spines were stiffened. Marrella has too many antennae, too few cephalic legs, and too few segments per leg to be a trilobite. It lacks the three pairs of legs behind the mouth that are characteristic of crustacea. The legs are also quite different from those of crustaceans. The identification of a diffraction grating pattern on well-preserved Marrella specimens proves that it would have harboured an iridescent sheen—and thus would have appeared colourful.[4] Dark stains are often present at the posterior regions of specimens, probably representing extruded waste matter.[5]

Ecology

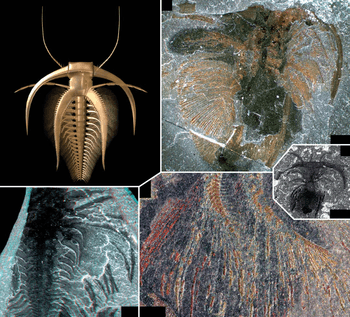

A – dorsal view on a rendered 3D model, based on own observations B–E – micrographs under polarized light

B – well preserved specimen USNM 83486f with the exopods in a "rusty" preservation (cf. García−Bellido and Collins 2006)

C – stereo image of specimen USNM 139665. Exopods of preceding limbs are super−imposing each other, separated by a thin layer of sediment

D – detail of specimen ROM 56766A in "rusty" preservation. Here the spines on the lateral side of the exopod ringlets are well preserved

E – one of the smallest specimens of M. splendens USNM 219817e that possesses preserved appendage remains

Marrella is thought to have been a benthic (bottom-dwelling) marine scavenger living on detrital and particulate material.[2] One exceptional specimen shows the organism fossilized in the act of moulting.[7]

Taxonomy

It is currently accepted that Marrella is a stem group arthropod—in other words, it is descended from an ancestor common to it and most or all of the later major arthropod groups. Despite its superficial similarity to the trilobites, it is no more closely related to this group than it is to any other arthropod.

Occurrence

Marrella is the most abundant genus in the Burgess Shale.[8] Most Marrella specimens herald from the 'Marrella bed', a thin horizon, but it is common in most other outcrops of the shale. Over 25,000 specimens have been collected;[7]5028 specimens of Marrella are known from the Greater Phyllopod bed, where they comprise 9.56% of the community.[9]

Marrellomorphs (Marrella-like organisms) are well distributed in other Cambrian deposits, and are indeed known from sediments as late as the Devonian.[10]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marrella. |

- "Marrella splendens". Burgess Shale Fossil Gallery. Virtual Museum of Canada. 2011.

- "Reconstruction of Marrella from the collections of Charles Doolittle Walcott". Historical Art Gallery. National Museum of Natural History.

References

- Gould, Stephen Jay (2000). Wonderful Life: Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. Vintage. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-09-927345-5. OCLC 45316756. Also OCLC 44058853.

- Whittington, H. B. (1971). "Redescription of Marrella splendens (Trilobitoidea) from the Burgess Shale, Middle Cambrian, British Columbia". Bulletin – Geological Survey of Canada. Geological Survey of Canada. 209: 1–24.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (2000). Wonderful Life: Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. Vintage. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-09-927345-5. OCLC 45316756. Also OCLC 44058853.

- Parker, A. R. (1998). "Colour in Burgess Shale animals and the effect of light on evolution in the Cambrian". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 265 (1400): 967–972. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0385. PMC 1689164.

- Whittington, H. B. (1978). "The Lobopod Animal Aysheaia pedunculata Walcott, Middle Cambrian, Burgess Shale, British Columbia". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 284 (1000): 165–197. Bibcode:1978RSPTB.284..165W. doi:10.1098/rstb.1978.0061.

- Haug, J. T., Castellani, C., Haug, C., Waloszek, D., Maas, A. (2012). A Marrella−like arthropod from the Cambrian of Australia: a new link between "Orsten"−type and Burgess Shale assemblages. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 58: 629–639. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0120

- García-Bellido, D. C.; Collins, D. H. (2004). "Moulting arthropod caught in the act". Nature. 429 (6987): 40. Bibcode:2004Natur.429...40G. doi:10.1038/429040a. PMID 15129272.

- Bottjer, David J.; Etter, Walter; Hagadorn, James W.; Tang, Carol M. (2002). Exceptional Fossil Preservation: A unique view on the evolution of marine life. Columbia University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-231-10255-1. OCLC 47650949.

- Caron, Jean-Bernard; Jackson, Donald A. (October 2006). "Taphonomy of the Greater Phyllopod Bed community, Burgess Shale". PALAIOS. 21 (5): 451–65. doi:10.2110/palo.2003.P05-070R. JSTOR 20173022.

- Siveter, Derek J.; Fortey, Richard A.; Sutton, Mark D.; Briggs, Derek E.G. & Siveter, David J. (2007). "A Silurian 'marrellomorph' arthropod". Proc Biol Sci. 274 (1623): 2223–2229. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0712. PMC 2287322. PMID 17646139.