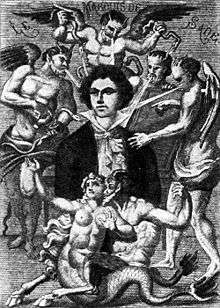

Marquis de Sade in popular culture

There have been many and varied references to the Marquis de Sade in popular culture, including fictional works, biographies and more minor references. The namesake of the psychological and subcultural term sadism, his name is used variously to evoke sexual violence, licentiousness and freedom of speech.[1] In modern culture his works are simultaneously viewed as masterful analyses of how power and economics work, and as erotica.[2] Sade's sexually explicit works were a medium for the articulation of the corrupt and hypocritical values of the elite in his society, which caused him to become imprisoned. He thus became a symbol of the artist's struggle with the censor. Sade's use of pornographic devices to create provocative works that subvert the prevailing moral values of his time inspired many other artists in a variety of media. The cruelties depicted in his works gave rise to the concept of sadism. Sade's works have to this day been kept alive by artists and intellectuals because they espouse a philosophy of extreme individualism that became reality in the economic liberalism of the following centuries.[3]

There has been a resurgence of interest in Sade in the past fifty years. Leading French intellectuals like Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault have published studies of Sade. There has been continuing interest in Sade by scholars and artists in recent years.[1]

Plays

- The play by Peter Weiss titled The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat, as performed by the inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the direction of the Marquis de Sade, or Marat/Sade for short, is a fictional account of Sade directing a play in Charenton, where he was confined for many years. In the play, the Marquis de Sade is used as a cynical representative of the spirit of the senses. He debates Jean-Paul Marat who represents the spirit of revolution.[4]

- The Japanese writer Yukio Mishima wrote a play titled Madame de Sade.

- The Canadian writer/actor Barry Yzereef wrote a play titled Sade, a one-man show set in Vincennes prison.

- Doug Wright wrote a play, Quills, a surreal account of the attempts of the Charenton governors to censor the Marquis' writing, which was adapted into the slightly less surreal film of the same name.

Films

Visual representations of Sade in film first began to appear during the surrealist period.[5] While there are numerous pornographic films based on his themes, the following is a list of the more significant representations:

- L'Age d'Or (1930), the collaboration between filmmaker Luis Buñuel and surrealist artist Salvador Dalí. The final segment of the film provides a coda to Sade's The 120 Days of Sodom, with the four debauched noblemen emerging from their mountain retreat.[5]

- The Skull (1966), British horror film based on Robert Bloch's short story "The Skull of the Marquis de Sade." Peter Cushing plays a collector who becomes possessed by the evil spirit of the Marquis when he adds Sade's stolen skull to his collection. The Marquis appears in a prologue as a decomposing corpse dug up by a 19th-century graverobber. In another scene, a character gives a brief, fictionalized account of Sade's life, emphasizing his "boogeyman" reputation.

- The film Marat/Sade (1966) directed by Peter Brook, who also directed the first English-language stage production. Patrick Magee plays the Marquis.[4]

- Marquis de Sade: Justine (1968), directed by Jesús Franco. Klaus Kinski appears as Sade, writing the tale in his prison cell.

- Eugenie… The Story of Her Journey into Perversion also known as Philosophy in the Boudoir (1969). Another Franco film, this one featuring Christopher Lee as Dolmance.

- De Sade (1969), romanticized biography scripted by Richard Matheson and directed by Cy Endfield. The film more or less presents the major incidents of Sade's life as we know them, though in a very hallucinatory fashion. The film's nudity and sexual content was notorious at the time of release, and Playboy ran a spread based around it. Keir Dullea plays the Marquis (here named Louis Alphonse Donatien) in a cast that includes Lilli Palmer, Senta Berger, Anna Massey and John Huston.

- Eugenie de Sade (1970), another of Jesús Franco's adaptations. Adapts Sade's story "Eugenie de Franval", accurately, though set in the 20th century.

- Beyond Love and Evil (1971), original title La philosophie dans le boudoir, French film loosely adapted from de Sade's play "Philosophy in the Bedroom". Set in the present day, a cult of depraved hedonists cavort at a remote, elegant mansion.

- Justine de Sade (1972), directed by Claude Pierson. An accurate rendition of Sade's tale, though lacking Franco's panache.

- Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975) directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini, is perhaps the most well-known cinematic adaptation of de Sade. Pasolini transplants Sade's novel updated to Fascist Italy as a commentary on the excesses of power and the commodification of man.

- Cruel Passion (1977), a toned-down re-release of De Sade's Justine, starring Koo Stark as the long-suffering heroine.

- House of De Sade (1977), X-rated film combines sex and S&M in a house haunted by de Sade's spirit. Vanessa del Rio stars.

- Waxwork (1988), another horror film. In this one, people are drawn through the tableaux in a chamber of horrors into the lives of the evil men they represent. Two of the characters are transported to the world of the Marquis, where they are tormented by Sade (J. Kenneth Campbell) and a visiting Prince, played by director Anthony Hickox.

- Marquis (1989), a French/Belgian co-production that combines puppetry and animation to tell a whimsical tale of the Marquis (portrayed, literally, as a jackass, voiced by François Marthouret) imprisoned in the pre-Revolution Bastille.

- Night Terrors (1994), another horror film playing on Sade's boogeyman image. A depiction of the Marquis's final days is intercut with the story of his modern day descendant, a serial killer. Tobe Hooper of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre fame directed, while horror icon Robert Englund of A Nightmare on Elm Street (and its many sequels and spin-offs) played both the Marquis and his descendant.

- Marquis de Sade, aka Dark Prince (1996). The Marquis (Nick Mancuso) seduces a young maiden from his jail cell. Loosely based on his life, and Sade's novel Justine.

- Sade (2000), directed by Benoît Jacquot. Daniel Auteuil plays Sade, here imprisoned on a country estate with several other noble families, sexually educating a young girl in the shadow of the guillotine.

- Quills (2000), an adaptation of Doug Wright's play by director Philip Kaufman. A romanticized version of Sade's final days which raises questions of pornography and societal responsibility. Geoffrey Rush plays Sade in a cast that also includes Kate Winslet, Joaquin Phoenix, and Michael Caine. The film portrays de Sade as a literary freedom fighter who is a martyr to the cause of free expression. The film's defense of de Sade is in essence a defense of cinematic freedom.[6] The film was inspired by de Sade's imprisonment and battles with the censorship in his society.[3] The film shows the strong influence of Hammer horror films, particularly in a key scene where asylum administrator Caine locks Winslet in a cell with a homicidal inmate, mirroring exactly a scene from The Curse of Frankenstein.

- Lunacy (2005, Czech title Šílení): Czech film directed by Jan Švankmajer. Loosely based on Edgar Allan Poe's short stories and inspired by the works of the Marquis de Sade. Sade figures as a character.

In art

Many surrealist artists had great interest in the Marquis de Sade. The first Manifesto of Surrealism (1924) announced that "Sade is surrealist in sadism". Guillaume Apollinaire found rare manuscripts by Sade in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. He published a selection of his writings in 1909, where he introduced Sade as "the freest spirit that had ever lived". Sade was celebrated in surrealist periodicals. In 1926 Paul Éluard wrote of Sade as a "fantastique" and "revolutionary". Maurice Heine pieced together Sade's manuscripts from libraries and museums in Europe and published them between 1926 and 1935. Extracts of the original draft of Justine were published in Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution.[5]

The surrealist artist Man Ray admired Sade because he and other surrealists viewed him as an ideal of freedom.[3] According to Ray, Heine brought the original 1785 manuscript of 120 Days of Sodom to his studio to be photographed. An image by Man Ray entitled Monument à D.A.F. de Sade appeared in Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution.[5]

Other works

- The writer Georges Bataille applied Sade's methods of writing about sexual transgression to shock and provoke readers.[3]

- In Harlan Ellison's science fiction anthology, Dangerous Visions (1967), Robert Bloch wrote a story entitled "A Toy For Juliette" whose title character was both named for, and used techniques based on, Sade's works.

- Bloch also wrote a short story called "The Skull of the Marquis de Sade", in which a collector becomes possessed by the violent spirit of the Marquis after stealing the titular item. The story was the basis for the film The Skull (1966), starring Peter Cushing and Patrick Wymark.

- Polish science fiction author Stanisław Lem has written an essay analyzing game-theoretical arguments that appear in Sade's novel Justine.[7]

- In Justine Ettler's The River Ophelia (1995), the protagonist Justine is writing her thesis on the work of Sade.

References

- Phillips, John, 2005, The Marquis De Sade: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280469-3.

- Guins, Raiford, and Cruz, Omayra Zaragoza, 2005, Popular Culture: A Reader, Sage Publications, ISBN 0-7619-7472-5.

- MacNair, Brian, 2002, Striptease Culture: Sex, Media and the Democratization of Desire, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-23733-5.

- Dancyger, Ken, 2002, The Technique of Film and Video Editing: History, Theory, and Practice, Focal Press, ISBN 0-240-80225-X.

- Bate, David, 2004, Photography and Surrealism: Sexuality, Colonialism and Social Dissent, I.B. Tauris, ISBN 1-86064-379-5.

- Raengo, Alessandra, and Stam, Robert, 2005, Literature and Film: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Film Adaptation, Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-23055-6.

- Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr. (1986). "Twenty-Two Answers and Two Postscripts: An Interview with Stanisław Lem". DePauw University.

.png)