Margaret Fountaine

Margaret Elizabeth Fountaine (16 May 1862 – 21 April 1940),[1] was a Victorian lepidopterist who published in The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation. She is also known for her personal diaries, which were edited into two volumes by W. F. Cater for the popular market and published posthumously.

Margaret Fountaine | |

|---|---|

Fountaine circa 1890 | |

| Born | Margaret Elizabeth Fountaine 16 May 1862 Norfolk, England |

| Died | 21 April 1940 (aged 77) |

| Citizenship | British |

| Known for | diarist |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | lepidopterist |

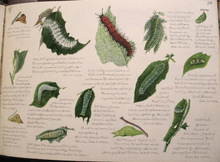

She was an accomplished natural history illustrator and had a great love and knowledge of butterflies, travelling and collecting extensively through Europe, South Africa, India, Tibet, America, Australia and the West Indies, publishing numerous papers on her work. She raised many of the butterflies from eggs or caterpillars, producing specimens of great quality, 22,000 of which are housed at the Norwich Castle Museum and known as the Fountaine-Neimy Collection. Her four sketch books of butterfly life-cycles are held at the Natural History Museum in London. The butterfly genus Fountainea was named in her honour.

Early life

Fountaine was born in Norwich, the eldest of seven children of an English country clergyman, Reverend John Fountaine of South Acre parish in Norfolk. John Fountaine had married Mary Isabella Lee (died 4 July 1906) on 19 January 1860 – she was the daughter of Reverend Daniel Henry Lee-Warner of Walsingham Abbey in Norfolk.[2] After her father's death in 1877 the family moved to Norwich.

Scientific practice

Fountaine travelled the world, collecting butterflies in sixty countries on six continents over fifty years,[3] and became an expert in tropical butterfly life-cycles.[4] Fountaine undertook most of her work collecting butterflies alone. In the summers she would return to England to arrange her collection of butterflies.[5] Fountaine compiled reports and drawings of the butterflies she found and sent them to entomological journals.[6] However, many of her discoveries of tropical butterflies were not written up.[5]

At the age of 27, Fountaine and her sisters became financially independent, having inherited a considerable sum of money from their uncle. Fountaine and her sister travelled to France and Switzerland, relying on the Tourist Handbook by Thomas Cook & Son. In Switzerland Fountaine felt the desire to acquire specimens of the Scarce Swallowtail and Camberwell Beauty butterflies, when discovering them in the valleys. Her interest in serious entomology grew and she started to use the Linnean rather than the common names for butterflies in her diary. Back in England, in the winter of 1895, she visited the estate of Henry John Elwes.[7] Elwes was a seasoned scientific traveller and had served as vice-president of the Royal Horticultural Society and was fellow of the Royal Society. His butterfly specimen collection was the largest private collection in the country, and Fountaine felt her entomological efforts were childish in comparison.[8]

Inspired, she travelled to Sicily with declared entomological ambitions. She was the first British butterfly collector to brave the south Italian Brigande. In Sicily she contacted the leading lepidopterist Signor Enrico Ragusa[8] and her research in Sicily led to her first publication on the subject in The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation in 1897. In the article she shared original knowledge of the local habitats and the butterfly varieties of Sicily. Her article was discussed in subsequent issues of The Entomologist. In 1897 several of her specimens were admitted to the British Museum's collection, which only accepted specimens of extraordinary quality.[9]

Following her expedition to Sicily Fountaine became a reputable collector and she formed professional relations with lepidopterists in the Natural History Department of the British Museum. In 1898 she travelled to Trieste, and meet entomologists in Hungary and Austria and Germany. Her second article in The Entomologist was on species variation. In 1899 she went on an expedition to the French Alps, where she met up with Elwes, whose reference book on European butterflies she used. Fountaine started to collect caterpillars in the French Alps, which she breed to produce adult butterfly specimens. In subsequent articles in The Entomologist, she wrote on food plants, plant hosts and the environmental conditions that were needed to grow perfect butterfly specimens. Back in Britain she was praised by Elwes for the quality of her work and her collection. In her diary she wrote "yet I know that if I did not turn my long days of toil to some scientific account when I got the chance, for what else have I toiled?".[9]

In 1898 she was elected as a fellow to the Royal Entomological Society and participated in the meetings. In her diaries she noted "I well know, of my being the sole representative of my sex present, with the exception of one lady visitor."[10] In the summer of 1900 she and Elwes collected butterflies in Greece and they published an account of their findings in The Entomologist. She cooperated with Elwes on his Grecian Lepidoptera exhibition.[11]

The money she had inherited from her uncle allowed her to travel extensively and expand her collection. It is however difficult to establish exact dates for her scientific expeditions, as she travelled mostly without a passport and did not record dates of arrival or departure in her diary. Between 1901 and her death in 1940 a number of important expeditions can nevertheless be established. In 1901 she went on an expedition to Syria and Palestine which led to a publication in The Entomologist. In the article she discussed the breeding of rare butterfly species. In Syria she hired the dragoman Khalil Neimy, who would become her travel companion. In 1903 she went on expedition to Asia Minor and she returned to Constantinople with nearly 1,000 butterflies. Her articles in The Entomologist on the expedition discussed seasonal and geographical influences on butterfly species, prompting notes and letters on the subject in subsequent issues.[10]

In 1904 and 1905 she was on scientific expeditions in South Africa and Rhodesia. There she wrote and illustrated sketch books to document eggs, caterpillars and chrysalises. Norman Riley, who went on to become the head of the Entomology Department at the British Museum, said "these sketchbooks were most beautifully done and illustrated the metamorphosis of many species which had not been previously known to science". Her research on the life cycles, food plants and seasonal timings of skin and colour changes was published in Transactions of the Entomological Society. This highly scientific article was reviewed and praised by entomologists. When she was back in London Fountaine set her African specimens. Subsequently, she went on expedition in the United States, Central America and the Caribbean. In Kingston, Jamaica she held a talk at the Kingston Naturalists' Club on "The sagacity of caterpillars".[10]

The scientific societies of Britain had historically excluded women. Like the Royal Entomological Society, the Botanical Society of London and Zoological Society only admitted women in the first half of the 19th century.[12] But when Fountaine attended the Second International Congress of Entomology held in Oxford in 1912, she was invited by Edward Poulton, president of the Linnean Society, to formally join the society. This marked the height of her entomological career. 15 years earlier Beatrix Potter had been unable to attend a reading of her own paper at the society, because she was a women. The botanist Marian Farquharson had petitioned learned societies to admit women. Farquharson's petition prompted members of the Linnean Society to put the matter to a vote in 1903. Female fellows were allowed, and in 1904 a ballot was taken on 15 prospective women fellows.[13]

In the run-up to World War I Fountaine was on expedition in India, Ceylon, Nepal and Tibet. On the trip she produced watercolours of caterpillars and butterflies, which were published in The Entomologist.[14] During the war Fountaine travelled to the US, and in 1917 published articles on her collection while volunteering for the Red Cross. In 1918 she ran out of money because she could not get her money wired to the USA. Thus she accepted paid work on specimens from the Ward's Natural Science Establishment. After the war Fountaine's last entomological expedition was to Khalil in the Philippines. An account of the expedition was published in The Entomologist and would 50 years later serve as a reference for conservation work.[15]

Fountaine was in her mid-sixties, and while she continued to travel for expeditions, she focused her efforts on watercolours and collecting. She only published the occasional note on the expeditions in The Entomologist. She travelled to West and East Africa, Indo-China, Hong Kong, the Malay States, Brazil, the West Indies and Trinidad. Her letters to Riley reveal that she was on the hunt for rare specimens. Aged 77 she suffered a heart attack in Trinidad. Reportedly she was found dead on a path on Mount St. Benedict, with a butterfly net in her hand.[15] The Benedictine monk who discovered her, Brother Bruno, brought her body back to Pax Guest House, where she was staying at the time. She was buried in an unmarked grave at Woodbrook Cemetery, Port of Spain, Trinidad.

It was after her death that she acquired general fame, when her collection and diaries were unsealed. After her death her literary and artistic talent for drawing butterflies became known more widely.[5] She left large collection of scientifically accurate watercolours to the British Museum of Natural History.[12]

Butterfly collection

Fountaine's extensive butterfly collection was only opened 38 years after her death. In accordance with her will it had been deposited at Norwich Castle Museum in the year of her death. She had also provided that the collection was only to be opened in 1978. A box and ten display cases with more than 22,000 specimens had been deposited.[16]

Diaries

In the box that was unsealed alongside her butterfly collection were Fountaine's diaries. She had filled twelve large volumes of cloth-bound books with some 3,203 pages and more than a million words, displaying a blend of Victorian reserve and startling candour.[17] The diaries were edited by the assistant editor of the Sunday Times W. F. Cater into two books, published under the titles Love among the Butterflies and Butterflies and Late Loves.[5]

Cater had produced an abridged 340 page version of her diaries, for the popular market. Fountaine's scientific work and career was reduced to her activities as a collector of butterflies. Cater compiled a selection of passages on romance and travel, while the work of collecting, breeding and mounting specimens got short shrift. The former senior curator of Natural History at the Norwich Castle Museum, Dr Tony Irwin had announced the existence of the diaries, and started to promote Fountaine's romantic life above her entomological contribution. He was of the opinion that her butterfly collection was "not outstanding" and said of her that "she was a girl in love" who "sought refuge in the pursuit of butterflies". A recent biography of Fountaine by Natascha Scott-Stokes draws a similar picture, condemning Fountaine as globetrotting "obscure lady amateur".[18]

During Fountaine's lifetime entomology was very fashionable among the affluent in Britain, and natural history societies were well attended. Naturalist publications were no longer produced only by elite scientists. A popular scientific publication was Emma Hutchinson's 1879 book "Entomology and Botany as Pursuits for Ladies", which encouraged women to study butterflies instead of just collecting them. Natural history was particularly popular among women in the Victorian era.[19] Far from being eccentric, Fountaine's work as entomologist followed in the footsteps of Victorian amateur women scientists. A survey of The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation reveals that all editions, except the 1917 and the 1925 edition, have article contributions from women. However, Fountaine's membership of learned societies was pioneering. In 1910 the Royal Entomological Society only had six female fellows.[20]

Eponyms

In 1971 A. H. B. Rydon named the butterfly genus Fountainea in Fountaine's honour.[21] Kenneth J. Morton named the Odonata species Ischnura fountainei in Fountain's honour after she collected the type specimen of the species.[22]

Bibliography

- Fountaine, M. E. 1897. Notes on the butterflies of Sicily. Entomologist 30: 4–11.

- Fountaine, M. E. 1898. Two seasons among the butterflies of Hungary and Austria. Entomologist 31: 281–289.

- Fountaine, M. E. 1902. Butterfly hunting in Greece in the year 1900. Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation 14: 29–35, 54–57.

- Fountaine, M. E. 1902. A few notes on some of the butterflies of Syria and Palestine. Entomologist 35: 60–63, 97–101.

- Fountaine, M. E. 1904. A “Butterfly Summer” in Asia Minor. Entomologist 37: 79–84, 105–108, 135–137, 157–159, 184–186.

- Fountaine, M. E. 1907. A few notes on some of the Corsican butterflies. Entomologist 40: 100–103.

- Fountaine, M. E. 1911. An autumn morning in the Alleghany Mountains. Entomologist 44: 14–15.

- Fountaine, M. E. 1911. IV. Descriptions of some hitherto unknown, or little known, larvae and pupae of South African Rhopalocera, with notes on their life-histories. Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London 59(1): 48–61. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.1911.tb03076.x

- Fountaine, M. E. 1911. Note on the roosting habits of Heliconia charitonia. Entomologist 44(583): 403–404): 403–404.

- Fountaine, M. E. 1911. Remarkable aberration of Terias elathea. Entomologist 44(575): 153–154.

- Fountaine, M. E. 1913. Five month's butterfly collecting in Costa Rica in the summer of 1911. Entomologist 46(601, 602): 189–195, 214–219.

- Fountaine, M. E. 1915. XIV. Notes on the life history of Papilio demolion, Cram. Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London 62(3‐4): 456–458. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.1915.tb02986.x

- Fountaine, M. E. 1917. A list of butterflies taken in the neighbourhood of Los Angeles, California. Entomologist 50: 154–156.

- Fountaine, M. E. 1921. Pyrameis gonerilla in New Zealand. Entomologist 54: 238–239

- Fountaine, M. E. 1925–1926. Amongst the Rhopalocera of the Philippines. Entomologist 58–59: 235–239, 263–265 (1925); 9–11, 31–34, 53–57 (1926).

- Fountaine, M. E. 1938. Rapid development of a tropical butterfly. Entomologist 71: 90

References

- Lepidopterology.com | Almanac | Years ago Archived 19 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Plantagenet Roll of the Blood Royal ... – Google Book Search at books.google.co.za

- "Cornucopia". archive.is. 23 July 2012. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012.

- Alafaci, Annette (2015). "Fountaine, Margaret Elizabeth". www.eoas.info. Encyclopedia of Australian Science. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Michael A. Salmon, Peter Marren, and Basil Harley (2000). The Aurelian Legacy: British Butterflies and Their Collectors. University of California Press. p. 201. ISBN 9780520229631.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Salmon, Marren, and Harley (2000), p. 200.

- Sophie Waring (2000). "Margaret Fountaine: A Lepidopterist Remembered". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. The Royal Society Publishing. 69 (1): 54. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2014.0063. PMC 4321127. PMID 26489183.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Waring (2000), p. 55.

- Waring (2000), p. 56.

- Waring (2000), p. 57.

- Waring (2000), pp. 56–57.

- Suzanne Le-May Sheffield (2004). Women and Science: Social Impact and Interaction. Rutgers University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780813537375.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Waring (2000), p. 53.

- Waring (2000), pp. 57–58.

- Waring (2000), p. 58.

- Salmon, Marren, and Harley (2000), p. 199.

- "Wings Worldquest". wingsworldquest.org. 29 June 2007. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007.

- Waring (2000), pp. 59–60.

- Waring (2000), p. 60.

- Waring (2000), p. 61.

- Rydon, A H B (1971). "The systematics of the Charaxidae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)". The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation. 83: 336–341 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Morton, K. J. (1905). "Odonata collected by Miss Margaret E. Fountaine in Algeria, with description of a new species of Ischnura". The Entomologist's Monthly Magazine. 41: 145–149 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.