Manor Farm, Ruislip

Manor Farm is a 22-acre (8.9 ha) historic site in Ruislip, Greater London.[2] It incorporates a medieval farm complex, with a main old barn dating from the 13th century and a farm house from the 16th. Nearby are the remains of a motte-and-bailey castle believed to date from shortly after the Norman conquest of England. Original groundwork on the site has been dated to the 9th century.

| Manor Farm | |

|---|---|

The Great Barn, built around 1280[1] | |

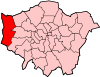

Location within Greater London | |

| General information | |

| Classification | Grade II and II* listed buildings |

| Location | Ruislip |

| Town or city | Greater London |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51.578206°N 0.428451°W |

| Completed | 13th century |

Ownership of the site passed to the King's College, Cambridge in the 15th century. The Great Barn and Little Barn were recognised by a member of the Royal Society of Arts in 1930 as in need of conservation, and in 1931 Manor Farm was included in the sale of Park Wood as a gift to the people of Ruislip. The site continued as a working farm until 1933, and is now run as a community resource by the London Borough of Hillingdon.

Throughout 2007 and 2008, the site was restored with funding from the National Lottery, and has become a heritage area for the London Borough of Hillingdon. Manor Farm is within the Ruislip Village Conservation Area.[3] Events are regularly held within the 13th-century Great Barn and around the rest of the site.

History

Origins

What remains of the motte-and-bailey castle can be seen today in part of the moat and bank on the site.[3] Today, the moat on the site is a scheduled monument, believed to have been extended to create an oval area upon which a wooden castle covering 350 foot (110 m) by 200 foot (61 m) was built, presumably for the landowner, Ernulf de Hesdin.[4] He was given control of the manor of Ruislip shortly after the Norman conquest, in recognition of his loyalty to William the Conqueror.[5] The castle is believed to have been built between 1066 and 1087, but does not appear in the 1086 Domesday Book and so could have been demolished or changed significantly.[5] It may never have been finished.

Ruislip parish was owned by the Benedictine Bec Abbey of Normandy between 1096 and 1404 during which time the prior built a home for himself on the site, surrounded by a moat.[1] During the 16th century, the remains of the motte-and-bailey site were used as the gardens of the Manor Farm House when it was built. In 1888 the moat extension was filled in by Henry James Ewer, who farmed on the site.[6] The moat's shape and the presence of traces of a fortified building have allowed this part of the site to be dated to the 11th century. However, the castle is believed to have been built around 1066 then either demolished or changed significantly as it does not appear as a castle in Domesday Book.[6]

The farm buildings date back to the 13th century with the Great Barn the most prominent.[1] The barn is the second largest such structure in Middlesex after another in Harmondsworth.[7] The Great Barn is constructed of English oak from the nearby Ruislip Woods. It was built to a design known as an aisled barn, whereby smaller out-shoots run alongside the main supports underneath one main roof.[3]

Ownership

Studies by English Heritage have found that the site originally functioned not only as the manorial court hall for Ruislip, but also as a working farm. The main building was built over two existing structures, possibly to accommodate the new lessee of the manor, Robert Drury, a former Speaker of the House of Commons. The study concluded this was most likely achieved by a team of masons and carpenters.[8] Manor Farm was also known as Ruislip Court until the 19th century.[9]

In 1451, ownership of the farm passed with the rest of Ruislip to King's College, Cambridge who remain titular Lords of the Manor.[8] King's completed two surveys of the manor during their ownership, in 1565 and 1750.[1]

The Farm House was built from locally produced bricks, tiles and timber in the 16th century, and served as the manorial court until 1925 when the last court was held. Work in the 18th and 19th centuries saw the windows and doorways replaced, while an extended kitchen was installed. The kitchen extension was replaced in 1958 as part of a general refurbishment of the house.[10]

Manor Farm and Park Wood were nearly demolished in the early 1900s to make way for a new development planned in partnership with King's College and the Ruislip-Northwood Urban District Council. A town planning competition was won by A & J Soutar from Wandsworth, who suggested a symmetrical design across the parish which would have seen a total of 7,642 new homes built.[11] St. Martin's Church would have been the only example of historical architecture left in Ruislip. An outline map of the new development proposal was made public on 30 November 1910 with few objections. A Local Board inquiry followed on 17 February 1911 which required negotiations with landowners to allow for a full planning scheme to be compiled. This was presented in February 1913 with an adaptation of the original Soutars plan and received approval from the Local Government Board in September 1914.[11] Three roads with residential housing, Manor Way, Windmill Way and Park Way were completed before the outbreak of the First World War when all construction work was halted. It was not resumed until 1919, though the plan was substantially scaled back as work slowed throughout the next decade.[12]

The protection of Manor Farm and the local woods from redevelopment was eventually confirmed in January 1930, after a visit by a member of the Royal Society of Arts to choose buildings that should be conserved. The Great Barn and Little Barn were selected, along with the old Post Office, the Old Bell public house and the Priest's House of the local church. The woods, part of the centre of the manor of Ruislip along with Ruislip village square, were included when King's College sold the land to the district in February 1931. Park Wood was sold for £28,100 with Manor Farm and the old Post Office included as a gift to the people of Ruislip.[5] King's had wished to also present the wood as a gift but was required by the University and College's Act to receive payment as it was the trustee of the land. Middlesex County Council contributed 75% of the cost as the urban district council argued that many of those who would make use of the land would be recreational day trippers from outside the district. Under a 999-year lease, the council agreed to maintain the wood and ensure no new buildings were constructed without the permission of the county council. An area of the wood to the south was not included in the lease agreement and three residential roads were later constructed on it.[13]

In 1932, the two cart sheds on either side of the lane leading into the farm were removed. That year, Councillor T. R. Parker purchased a plot of land on the site from King's College. Manor Farm continued as a working farm until the following year,[1] when the local council began to sell off much of the land surrounding the buildings for housing developments.[14] Councillor Parker presented his land to the Ruislip Village Trust as the site of a future public hall, and the Trust passed it to the urban district council in 1964 stipulating that that would be the sole use. The council obliged and the Winston Churchill Hall was built in 1965.[14]

A smaller barn built in the 16th century, the Little Barn, was converted to a library and opened on 2 November 1937.[14] The original cowbyre was destroyed by fire in 1979 and was rebuilt as an exhibition centre.[1] An archaeological excavation was carried out by the Museum of London Archaeological Service in 1997 around the Farm House. This discovered the remains of the old priory were beneath the house, as this had been the bailey, surrounded by the motte.[5]

Restoration

The site was refurbished with funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund in April 2007 with the work completed in June the following year.[15] This included the renovation of the Grade II listed[16] Manor Farm library as part of a borough-wide programme by the London Borough of Hillingdon.[17] The Duck Pond Market began in the Great Barn in December 2008, following the refurbishment, and runs twice a month.[18] Winston Churchill Theatre, not included in the original restoration work, received a £370,000 grant from Hillingdon Council in March 2011 to enable its refurbishment.[19] The other buildings on the site are used as an Exhibition venue (the Cow Byre Gallery), community spaces (The Stables and the Manor Farm Community Hut) and as a small interpretation centre and base of the Hillingdon Music Service (Manor Farm House).

Since 6 September 1974, all the buildings on the site are Grade II listed,[20][21][22][23] except for the Great Barn, which is Grade II*.[24]

Comparable structures

Other moated medieval farm complexes survive in the nearby area at Headstone Manor and (without a surviving moat) at Pinner Park. Traces of a moat survived at Harmondsworth Great Barn until 1968.

References

- Citations

- McBean, K. J. (21 March 2011). "A history of the Manor Farm site". London Borough of Hillingdon. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- "Manor Farm". West Waddy ADP. 2010. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- "Manor Farm". London Borough of Hillingdon. 23 March 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- Cotton, Johnathan; Mills, John; Clegg, Gillian (1986). Archaeology in West Middlesex. Uxbridge: London Borough of Hillingdon. ISBN 0-907869-07-6.

- Bowlt 2007, p.35

- Bowlt 1994, p.12

- Bowlt 1994, p.14

- "Manor Farm Ruislip". English Heritage. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- Bowlt 1994, p.16

- Newbery, Mary; Cotton, Carolynne; Packham, Julie Ann; Jones, Gwyn (1996). Around Ruislip. Stroud: The Chalfont Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7524-0688-4.

- Bowlt 1994, p.96

- Bowlt 1994, p.100

- Bowlt 1994, p.115

- Bowlt 1994, p.119

- "Manor Farm, Ruislip". Ruislip, Northwood & Eastcote Local History Society. Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- "Manor Farm Library, Ruislip". London Borough of Hillingdon. 20 April 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- "Speak up! Libraries turn new page". BBC News. 19 September 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- "Ruislip Duck Pond Market". Duck Pond Market. Archived from the original on August 27, 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- Cracknell, James (14 March 2011). "Churchill's theatre shows fighting spirit". Uxbridge Gazette. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Historic England. "Cowshed and sties to North-West of Manor Farmyard (1192696)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Historic England. "Cowshed to East of Manor Farmyard (1080267)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Historic England. "Manor Farmhouse (1080162)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Historic England. "Small Barn to South of Manor Farmyard (1192707)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Historic England. "Great Barn to West of Manor Farmyard (1358359)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Bibliography

- Bowlt, Eileen. M. (1994) Ruislip Past. London: Historical Publications ISBN 0-948667-29-X

- Bowlt, Eileen. M. (2007) Around Ruislip, Eastcote, Northwood, Ickenham & Harefield. Stroud: Sutton Publishing ISBN 978-0-7509-4796-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manor Farm, Ruislip. |

- Manor Farm - official site

- Timeline of the site — Ruislip, Northwood & Eastcote Local History Society

- Manor Farm - Ruislip — Great Barns