Manganese, Minnesota

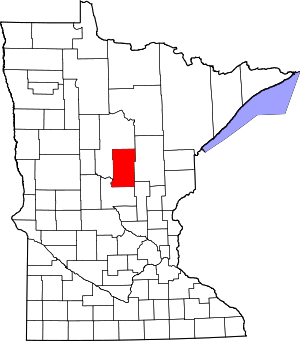

Manganese is a ghost town and former mining community in the U.S. state of Minnesota that was inhabited between 1912 and 1960. It was built in Crow Wing County on the Cuyuna Iron Range in sections 23 and 28 of Wolford Township, about 2 miles (3.2 km) north of Trommald, Minnesota. After its formal dissolution, Manganese was absorbed by Wolford Township; the former town site is located between Coles Lake and Flynn Lake. First appearing in the U.S. Census of 1920 with an already dwindling population of 183,[2] the village was abandoned by 1960.[3][4]

Manganese | |

|---|---|

Ruins and crumbling concrete foundation of the old Fitger Hotel in Manganese, October 2016 | |

| Etymology: Manganese | |

Manganese  Manganese | |

| Coordinates: 46°31′39″N 94°00′35″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Minnesota |

| County | Crow Wing |

| Founded | March 13, 1912 |

| Incorporated | November 10, 1913 |

| Dissolved | July 17, 1961 |

| Elevation | 1,250 ft (380 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| GNIS feature ID | 654881[1] |

Manganese was one of the last of the Cuyuna Range communities to be established, and named after the mineral located in abundance near the town. Manganese was an incorporated community, built on land above the Trommald formation, the main ore-producing unit of the North Range district of the Cuyuna Iron Range, unique due to the amount of manganese in part of the of iron formation and ore. The Trommald formation and adjacent Emily district are the largest resource of manganese in the United States. The community was composed of many immigrants who had fled the various natural disasters, social upheavals, and political upheavals on the European continent during the late 19th and early 20th centuries before the onset of World War I.[5]

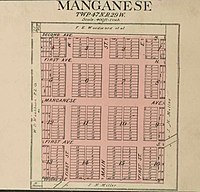

Manganese was laid out with three north–south and five east–west streets. Concrete sidewalks and curbing lined the clay streets, which were never paved. At its peak around 1919, Manganese had two hotels, a bank, two grocery stores, a barbershop, a show hall, and a two-room school, and housed a population of nearly 600. After the end of World War I, the population of Manganese went into steady decline as mining operations shut down; along with the resulting quagmire of the clay streets from the spring rains, this led to the community's eventual abandonment and formal dissolution in 1961. Today, the privately owned land is starting to undergo a sort of resettlement, as the old wooded lots are being cleared and redeveloped as primitive campsites.[6]

History

The area around Manganese, and modern-day Crow Wing County, was initially inhabited by three distinct populations of Native Americans vying for control of the lands that would become the Cuyuna Range. The Arapaho living along the western border of the Great Lakes were quickly displaced by the Dakota and Ojibwe nations; frequent conflicts between the Dakota and Ojibwe eventually resulted in undisputed control of the region by the Ojibwe. In 1855, a treaty between the Ojibwe and the U.S. Government, signed by chief Hole in the Day in what was then Minnesota Territory, secured Ojibwe hunting and fishing rights while ceding land which would become the Cuyuna Range to European-Americans looking to build new settlements in the region.[7] The Minnesota Territorial Legislature enacted the creation of Crow Wing County on May 23, 1857.[8] Minnesota was admitted as the 32nd U.S. state on May 11, 1858, and Deerwood, Minnesota (originally named Withington), was the first Cuyuna Range community, settled in 1882.[9][10]

The discovery of the Cuyuna Iron Range was an accident, made by the chance observation of a compass needle irregularity while Cuyler Adams was exploring the area with his St. Bernard, named "Una". It occurred to him that a vast body of iron ore, buried deep underground, might be responsible for the discrepancy. Nearly fifteen years after painstakingly mapping these compass deflections, test drilling by Adams in May of 1903 resulted in manganiferous ore near Deerwood.[11] Thirteen years after ore discovery by the Merritt Brothers trigged an iron rush to the Mesabi Range,[12] another iron rush began in Minnesota,[13] and new mining communities began to blossom along the width and breadth of the "Cuyuna" Iron Range, named by combining the first syllable of Adams' given name and the name of his dog.[9]

Establishment and community

Manganese was platted by the Duluth Land and Timber Company on February 5, 1911,[14] established on March 13, 1912, and incorporated on November 10, 1913, with 960 acres (390 ha) inside the corporate limits. All of the lots sold within seven weeks of platting, for $100 to $350 each, a result of the rapid mining development in the area. Manganese was named for the mineral located in abundance nearby.[15] The mines surrounding the community included the Algoma mine, owned by the Onaham Iron Company and founded in 1911; the Gloria and Merrit No. 2 mines, both owned by the Hanna Mining Company and founded in 1916; the Milford mine, owned by the Cuyuna-Minneapolis Iron Company and founded in 1917, and the Preston mine, owned by Coates and Tweed and founded in 1918.[16][17][18] The sixth of the Cuyuna Range communities to be established (after Deerwood, Cuyuna, Crosby, Ironton, and Riverton),[10][19] the new town was touted as the "Hibbing of the Cuyuna Range".[14]

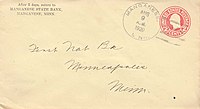

An official U.S. Post Office opened in 1912 and remained in operation through 1924.[15][20] In 1914, the town site had a crew of men and teams building streets with concrete sidewalks and curbing (although the clay roads were never paved), and the Fitger Brewing Company built a $10,000, two-story hotel, complete with dining room and bar. By 1919, Manganese had two hotels, a bank, two grocery stores, two butcher shops, a lumber yard, a bakery, a livery stable, a barbershop, a pool room, a show hall, a dog pound, and a two-room school, and housed a population of nearly 600. That same year, the village issued a bond for a $30,000 waterworks project, and the Pastoret Company of Duluth built a 100-foot (30 m) water tower with a 30,000-US-gallon (113,562 l) capacity.[14][21][22] Manganese and other Cuyuna Range communities benefited greatly from an unusual situation created by an ad valorem property tax on unmined natural ore,[23] resulting in huge amounts of unforeseen revenue, great expenditures of which were made on public works and improvements.[24]

After the discovery of ore near Deerwood, Adams approached James J. Hill, then president of the Northern Pacific Railway, asking for a discounted rate to haul Cuyuna Range ore to Duluth (the rate from the Mesabi Range, which had richer ore, was one dollar per ton). Hill refused, so Adams went to Thomas Shaughnessy, president of the Canadian Pacific Railway and a competitor of Hill, who readily agreed to build 100 miles of railroad with the guarantee to haul ten million tons of ore at sixty-five cents per ton.[11][25] At the time, the Canadian Pacific controlled the Soo Line Railroad, having secured the railroad's funded debt,[26] and the Soo Line came to furnish rail transportation to Manganese and the surrounding mines. In 1914, the Soo Line Railroad constructed a siding and began excavation for a 24-by-60-foot (7 m × 18 m) passenger and freight depot with a 300-foot-long (91 m) platform.[27][28][29] Passenger connections with the other Cuyuna Iron Range towns were available three times daily through the operation of buses owned by the Cuyuna Range Transportation Company.[14][30] It was speculated that Henry Ford once visited Manganese when he was exploring the acquisition of the Algoma mine on behalf of the Ford Motor Company. Ford was never observed, but his private rail car, the Fair Lane,[31] with the familiar Ford oval and the gilded words "Ford Motor Company, Dearborn, Michigan", was seen parked on the Manganese siding.[14]

The community was composed of many immigrants, including Finns, Croatians, Austrians, Swedes, Irish, Australians, English, Norwegians, Germans, Polish, Slovenians, Hungarians, Serbs, and French.[5][14][32] Children attended school in Manganese through the eighth grade, attending high school in nearby Crosby, Minnesota. Known then as Independent School District No. 86, the school had indoor plumbing and later its own well, constructed by the Works Progress Administration.[32][33] Over time, the village of Manganese had three wells, all of which collapsed at some point due to the heavy clay soils.[32]

Manganese boasted of its high-grade manganiferous ores. During late World War I, all of the mines surrounding the community were running at full capacity, furnishing about 90% of the manganese used during the war. By 1920, the combined payrolls of these mines totaled $160,000.[14] Seven citizens from Manganese served in the military during World War I, including Harry Hosford,[34] who later survived the Milford mine disaster. Many of Manganese's residents worked in the Milford mine, which flooded on February 5, 1924, a result of blasting in a drift that extended beneath Foley Lake. Forty-one miners were killed in what was Minnesota's worst mining disaster; only seven, including Hosford, made it to safety.[35][36] Many Manganese residents were superstitious and convinced that both the town of Manganese, and the Milford mine, were cursed.[37][38]

After the World War I armistice was signed, the demand for manganiferous ore decreased.[14] With the advent of the Great Depression, mining operations ceased. The Soo Line tore up the track to Manganese in 1930. Little employment was left in the community, and residents relocated to find new jobs. The last shipment of ore from the Algoma and Gloria mines occurred in 1931; the Milford mine closed in 1932, although the Merritt mine continued to produce ore intermittently until 1943.[35][39] Very few photos of Manganese are known to exist. Never a wealthy community, residents had no money for cameras, a luxury item during the Depression.[32] In 1938, a Wesleyan Methodist Church and Sunday school was founded. There were generally four Sunday school classes, based on the ages of the children. Occasional revival meetings were held, and guest pastors came in for services. The congregation came from Trommald, Mission, Wolford, and Perry Lake, in addition to Manganese. After World War II, the church was sold and torn down after the congregation was no longer able to appoint a pastor.[40] As mining operations began to shut down, residents gradually started moving their homes out of town for relocation to other communities in the region.[41]

Abandonment and current use

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1920 | 183 | — | |

| 1930 | 96 | −47.5% | |

| 1940 | 62 | −35.4% | |

| 1950 | 41 | −33.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[42] | |||

Most of the remaining residents moved out around 1955.[43] Structures that were not moved out of the community were torn down. After all of the residents left, the clay roads continued to be maintained, and the street lights remained on for at least a decade.[14][32][33] In 1959, the village of Ironton, one of the creditors for the village of Manganese, petitioned Crow Wing County for the community's dissolution. Einer R. Andersen, then Crow Wing County Auditor, was appointed as its receiver, and creditors of the village of Manganese were given six months to file a claim. Notices sent to the last known village officers were refused. Bids were accepted for the sale of the Manganese water tower and the frame building that had housed the village hall, with the condition that all debris be disposed of at the expense of the buyer. The steel water tower, with an estimated weight of 100 short tons (91,000 kg) of scrap metal, was valued at $1,200; however, the sale and salvage of the water tower yielded net proceeds of only $200. Ironically, the surviving Cuyuna Iron Range municipally-owned elevated metal water tanks (in the towns of Crosby, Cuyuna, Deerwood, Ironton, and Trommald) were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.[24][44] The final hearing regarding the dissolution of Manganese was held on July 17, 1961. Manganese was formally dissolved and absorbed by Wolford Township.[3][45]

After the town was abandoned, only remnants of sidewalks, rubble, building foundations, old tires, plastic, pieces of clothing, beer cans, and other abandoned items remained.[14][22][37] The site was slowly overgrown with willow, aspen, and other trees; roots, shrubs, and grass began to heave and crack the concrete sidewalks and overtake the remaining grid pattern of roads. Most of the remaining structures succumbed to the elements. Old building foundations and basements, covered with graffiti, were engulfed by the brush.[14][47] Trees covered what was once a land occupied by numerous buildings, and the entire town site was consumed by the steady growth of natural vegetation. In 2003, the majority of the land which comprised the former town site was purchased, and a gate was posted along with a "no trespassing" sign at the southeast entrance to the former town.[47] The privately owned land was sold again in 2006; today, it is starting to undergo a sort of resettlement.[48] Called Manganese Base Camp, the old wooded lots, about 0.3 acres (0.12 ha) each, are being cleared and redeveloped as primitive campsites, without electricity, running water, or waste disposal services. Since 2017, Base Camp has hosted an annual Manganese Days Festival. The event is open to the public as a way to honor the former village, learn of its history, and explore the old town site of Manganese.[6]

Geology

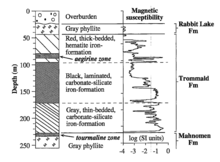

Manganese lay atop the iron-rich Trommald formation, the main ore-producing unit of the North Range district of the Cuyuna Iron Range.[49] The Trommald formation has been variously correlated with other iron formations of the Animikie Group,[50] deposited during the early Proterozoic age,[49][51] and is unique in the Lake Superior region because of the amount of manganese in part of the iron formation and ore.[52][53] In general, the stratigraphic column of the Trommald formation ranges from 45 to 820 feet (14 to 250 m) thick and consists of at least two mappable iron formation facies, one thick-bedded and cherty, divided by an aegirine zone, the other thin-bedded and slaty with a tourmaline zone at its base.[54][55] The facies are sometimes separated by a black laminated carbonate-silicate iron formation. Gray phyllite lies above and below,[55] capped with topsoil consisting of overlying morainic material and clay-rich till.[50]

It is not possible to determine the mineral content in the iron formation from top to bottom in any one location due to the great diversity of ore textures and the shape of the ore bodies.[56] Considerable variation exists in the character and composition of the ores, varying greatly from 20 to 60 percent iron and 0.5 to 15 percent manganese, with local areas of manganese as high as 50 percent.[49][50][57] Most manganese is finely disseminated as an integral part of the iron ore.[58] Ores of the Milford mine were brown and manganiferous; ores from the Gloria mine were black and slaty brown maganiferous; ores from the Merritt mine were red brown to black and richly manganiferous; ores from the Algoma mine were ferruginous manganese.[39] The ores contained on average about 43% iron and 10% manganese.[51]

The Trommald formation and adjacent Emily district are the largest resource of manganese in the United States.[50][59][60] The largest high-grade deposit of manganiferous ore is located about 14 miles (23 km) north of Manganese on a 5-acre (2.0 ha) site at the edge of Emily.[61][62][63] Valuable in steel and aluminum production, manganese is also used to make batteries.[64][65] There is a local push to "scram" the stockpiles of ore found in the old waste rock of the Cuyuna Iron Range. This mining process is significantly less invasive than traditional blasting and crushing, but processing of some stockpiles would disrupt the Cuyuna Lakes Mountain Bike Trails,[66][67] which opened in June 2011[68] and have been a boon to tourism since the last manganiferous ore was shipped from the Cuyuna Range in 1984.[69] This potential for ore processing has created debate as to whether mining and mountain biking can coexist.[70] The use of former underground Cuyuna Range mines as a means of compressed-air energy storage has also been investigated by researchers at the University of Minnesota.[71]

Geography and climate

Manganese lay at an elevation of 1,250 feet (380 m) in Crow Wing County, Minnesota, about 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Brainerd and 91 miles (146 km) west-southwest of Duluth.[1][50] The nearest cities to Manganese were Trommald, approximately 2 miles (3 km) to the south-southwest, and Wolford, approximately 2 miles (3 km) to the northeast.[63] Manganese was located to the west of Crow Wing County Road 30, about 5 miles (8 km) north of Minnesota State Highway 210 and 3 miles (5 km) west of Minnesota State Highway 6.[72]

Manganese was laid out with three primary north–south streets: First Street East, Main Street, and First Street West. Second Avenue North, First Avenue North, Manganese Avenue, First Avenue South (now Old Manganese Road), and Second Avenue South traversed Manganese from east to west.[73] The Soo Line right of way bisected the community on the east side of Manganese from the southwest to the northeast.[74] First Avenue North extended about 1.9 miles (3.1 km) to the Milford mine.[75]

Manganese was in the Laurentian Mixed Forest Province in the Brainerd Lakes Area of north central Minnesota. Precipitation ranges from about 21 inches (53 cm) annually along the western border of the forest to about 32 inches (81 cm) at its eastern edge. Average annual temperatures are about 34 °F (1 °C) along the northern part of the forest, rising to 40 °F (4 °C) at its southern extreme.[76]

July is the warmest month, when the average high temperature is 80 °F (27 °C) and the average low is 56 °F (13 °C). January is the coldest, with an average high temperature of 20 °F (−7 °C) and average low of 0 °F (−18 °C).[77] The spring rains wreaked havoc on Manganese's clay streets, which was cited as one of the reasons for its abandonment.[22][32]

References

- "Manganese". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- Census 1922, p. 238.

- Census 1964, p. 26.

- Sutherland 2016, p. 185.

- Sutherland 2016, p. 89.

- "Manganese Base Camp". Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Sutherland 2016, pp. 47, 48, 50, 51.

-

- Upham 2001, p. 158.

- "A Guide to Minnesota Communities". LakesnWoods. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Clark, Neil M. (February 1922). "How the Needle of a Compass Pointed the Way to Fortune". The American Magazine. New York: The Crowell Publishing Company. 93: 86–93. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Havinghurst 1958, pp. 75–76.

- Borchert 1959, p. 64.

- Anon. "Manganese, Minnesota". Archival Material. Crosby, MN: Cuyuna Iron Range Heritage Network.

- Upham 2001, p. 160.

- Minnesota Historical Records Survey Project 1940, pp. 110, 114, 117, 119.

- Lake Superior Iron Ore Association 1952, pp. 29, 31, 36, 38.

- Beltrame, R. J. (1977). Directory of Information on Cuyuna Range Geology and Mining. University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy (Report). University of Minnesota: Minnesota Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Sutherland 2016, p. 11.

- "Crow Wing County". Jim Forte Postal History. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- Foote, L. L. (March 24, 1954). "Manganese – Ghost Town". Crosby-Ironton Courier (MN). p. 1.

- Cuyuna Country Heritage Preservation Society 2002, p. 190.

- Roberts, David R. (April 1950). "Tax Valuation of Minnesota Iron Ore". Minnesota Law Review. 34 (5): 400. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- "Nomination Form: Cuyuna Iron Range Municipally-Owned Elevated Metal Water Tanks Thematic Resources" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places. 1979. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- Sutherland 2016, pp. 65, 78.

- "Soo Line Railroad (Minneapolis, St. Paul & Sault Ste. Marie)". American-Rails.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- "Manganese a Busy Town". Brainerd Dispatch (MN). July 3, 1914.

- Leighton 1998, p. 19.

- West, Dan. "Past and Present Minnesota Railroad Stations". Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- "Manganese". The Soo. The Soo Line Historical and Technical Society. 15 (1). Winter 1993.

- "Henry Ford's Private Railroad Car "Fair Lane", 1921". The Henry Ford. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Sloan, Jim (May 8, 1985). "Manganese Revisited". Brainerd Dispatch (MN). pp. 1N, 3N.

- Cuyuna Country Heritage Preservation Society 2002, p. 191.

- Minnesota War Records Commission. "Manganese, Minnesota". World War I Military Service Records, 1918–1920. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society.

- Fitzgerald, John (November 3, 2016). "Milford Mine Disaster, 1924". MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 14, 2016. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- Sutherland 2016, pp. 5, 22, 144, 231.

- Christensen, G. (May 25, 2005). "Guide to the Ghost Towns of Minnesota". Ghost Town USA. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Jones, Hannah (September 16, 2019). "The ghostly legacy of Minnesota's Milford Mine disaster". City Pages. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Schmidt 1963, pp. 67, 68, 69.

- Cuyuna Country Heritage Preservation Society 2002, p. 193.

- Sutherland 2016, pp. 186, 240.

- United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- Sutherland 2016, p. 186.

- Sutherland 2016, p. 212.

- Manganese, Minnesota. "Crow Wing County: Manganese". Records, 1913-1960. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society.

- "Landview". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Manganese, Minnesota". Wikimapia. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Property Information". Crow Wing County, Minnesota. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- Melcher, Frank; Morey, G. B.; McSwiggen, Peter L.; Cleland, J. M.; Brink, S. E. (1996). "RI-46 Hydrothermal Systems in Manganese-Rich Iron-Formation of the Cuyuna North Range, Minnesota: Geochemical and Mineralogical Study of the Gloria Drill Core". University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy. Minnesota Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Morey, G. B.; Broberg, J.; Beltrame, R. J.; Holtzman, R. C. (1977). Manganese-bearing ores of the Cuyuna Iron Range, east-central Minnesota, Phase 1. University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy (Report). Minnesota Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Cuyuna Iron Range District". Porter GeoConsultancy. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Schmidt 1963, p. 57.

- Morey 1990, p. 8.

- Beltrame, R. J.; Holtzman, Richard C.; Wahl, Timothy E. (1981). "RI-24 Manganese Resources of the Cuyuna Range, East-Central Minnesota". University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy. Minnesota Geological Survey. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- McSwiggen, Peter L.; Morey, Glenn B.; Cleland, Jane M. (1994). "The Origin of Aegirine in Iron Formation of the Cuyuna Iron Range, East-Central Minnesota" (PDF). The Canadian Mineralogist. 32: 591. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Schmidt 1963, pp. 20, 55, 68.

- Morey 1990, pp. 11, 22.

- Schmidt 1963, p. 48.

- Robertson, Tom (June 4, 2009). "Underground in Emily, a mother lode of manganese". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Sutherland 2016, p. 4.

- Johnson, Brooks; Lovrien, Jimmy (1 September 2018). "Minnesota manganese deposit sits untapped despite growing market". Duluth News Tribune. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Crow Wing Power announces partnership to develop Emily manganese deposit". Brainerd Dispatch (MN). June 7, 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Distance From To: Calculate distance between two addresses, cities, states, zipcodes, or locations". Map Developers. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Burton, Michael; Egan, Kevin (January 2015). "Bringing Mining Back to the Cuyuna Range?" (PDF). Laurentian Vision Project. Brainerd Lakes Area Economic Development Corporation. p. 18. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Sutherland 2016, pp. 184, 243.

- "Cuyuna Range mining talk hails old ghosts". Minnesota Brown. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- "Cuyuna Mountain Bike Trail System". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- "Brainerd MN Bike Trails: Cuyuna Mountain Bike Trail System". Brainerd.com. Archived from the original on 24 June 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- Rosemore, Lisa (February 28, 2014). "CUYUNA: The Lost Range". Hibbing Daily Tribune. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Richardson, Renee (July 12, 2014). "Mining, mountain biking come head to head on Cuyuna Range". Inforum. Forum Communications Company. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Fosnacht, D. R.; Wilson, E. J.; Marr, J. D.; Carranza-Torres, C.; Hauck, S. A.; Teasley, R. L. (2015). Compressed-Air Energy Storage (CAES) in Northern Minnesota Using Underground Mine Workings and Above Ground Features (PDF) (Report). University of Minnesota Duluth: Natural Resources Research Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Minnesota Official Highway Map (Map). [1:760,320]. Minnesota Department of Highways. 1960. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- Standard Atlas, Crow Wing County, Minnesota (Map). [1:4,800]. Chicago: Geo. A. Ogle & Co. 1913. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- "Crow Wing County GIS Public Map Service". Crow Wing County, Minnesota. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Terrell, Michelle M.; Gronhovd, Amanda (March 2015). Milford Mine National Register Historic District, Crow Wing County, Minnesota: Cultural Landscape Report (Report). Crow Wing County, Minnesota. p. 51. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Laurentian Mixed Forest Province". Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on May 20, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- "Manganese, MN Monthly Weather". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

Sources

- Borchert, John R. (1959). Minnesota's Changing Geography. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0816668397. Retrieved July 5, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cuyuna Country Heritage Preservation Society (2002). Cuyuna Country: A People's History. II (First ed.). Brainerd, MN: Bang Printing Company. ISBN 978-0967745008.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Havinghurst, Walter (1958). Vein of Iron: The Pickands-Mather Story. Cleveland and New York: World Publishing Company. ASIN B0007DMAS0. Retrieved November 5, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lake Superior Iron Ore Association (1952). Lake Superior Iron Ores: Mining Directory and Statistical Record of the Lake Superior Iron Ore District of the United States and Canada (Second ed.). Cleveland: Lake Superior Iron Ore Association. OCLC 1025093.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leighton, Hudson (1998). Gazetteer of Minnesota Railroad Towns, 1861–1997. Roseville, MN: Park Genealogical Books. ISBN 978-0915709618. Retrieved July 27, 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Minnesota Historical Records Survey Project (1940). The Cuyuna Range: A History of a Minnesota Iron Mining District. St. Paul, MN: The Minnesota Historical Records Survey Project. ASIN B07HV921QQ. Retrieved August 12, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morey, G. B. (1990). Geology and Manganese Resources of the Cuyuna Iron Range, East-Central Minnesota (PDF). St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Geological Survey. ISSN 0544-3105. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schmidt, Robert Gordon (1963). Geology and Ore Deposits of the Cuyuna North Range Minnesota (PDF). Washington: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-1288964765. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sutherland, Frederick (2016). The Cuyuna Iron Range: Legacy of a 20th Century Industrial Community (Thesis). Michigan Technological University. S2CID 164100360. Retrieved July 13, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- United States, Bureau of the Census (1922). Fourteenth Census of the United States: 1920 (PDF). III. Washington: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-1396464294. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- United States, Bureau of the Census (1964). U.S. Census of Population, 1960 (PDF). I, Pt. 25. Washington: Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-1390260830. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 9, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- Upham, Warren (2001). Minnesota Place Names: A Geographical Encyclopedia (Third ed.). St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0873513968. Retrieved July 27, 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manganese, Minnesota. |