Major chord

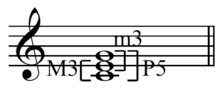

In music theory, a major chord is a chord that has a root, major third, and perfect fifth. When a chord has these three notes alone, it is called a major triad. For example, the major triad built on C, called a C major triad, has pitches C–E–G:

| Component intervals from root | |

|---|---|

| perfect fifth | |

| major third | |

| root | |

| Tuning | |

| 4:5:6 | |

| Forte no. / | |

| 3-11 / |

In harmonic analysis and on lead sheets, a C major chord is usually notated C, Cmaj or CM. A major triad is represented by the integer notation {0, 4, 7}.

A major triad can also be described by its intervals: the interval between the bottom and middle notes is a major third and the interval between the middle and top notes is a minor third. By contrast, a minor triad has a minor third interval on the bottom and major third interval on top. They both contain fifths, because a major third (four semitones) plus a minor third (three semitones) equals a perfect fifth (seven semitones).

In Western classical music from 1600 to 1820 and in Western pop, folk and rock music, a major chord is usually played as a triad. Along with the minor triad, the major triad is one of the basic building blocks of tonal music in the Western common practice period and Western pop, folk and rock music. It is considered consonant, stable, or not requiring resolution. In Western music, a minor chord "sounds darker than a major chord".[1]

Some major chords with additional notes, such as the major seventh chord, are also called major chords. Major seventh chords are used in jazz and occasionally in rock music. In jazz, major chords may also have other chord tones added, such as the ninth and the thirteenth scale degrees.

Inversions

A given major chord may be voiced in many ways. For example, the notes of a C major triad, C–E–G, may be arranged in many different vertical orders and the chord will still be a C major triad. However, if the lowest note (i.e. the bass note) is not the root of the chord, then the chord is said to be in an inversion: it is in root position if the lowest note is the root of the chord, it is in first inversion if the lowest note is its third, and it is in second inversion if the lowest note is its fifth. These inversions of a C major triad are shown below.

The additional notes above the bass note can be in any order and the chord still retains its inversion identity. For example, a C major chord is considered to be in first inversion if its lowest note is E, regardless of how the notes above it are arranged or even doubled.

Major chord table

In this table, the chord names are in the leftmost column. The chords are given in root position. For a given chord name, the following three columns indicate the individual notes that make up this chord. Thus in the first row, the chord is C major, which is made up of the individual pitches C, E and G.

Chord Root Major third Perfect fifth C C E G C♯ C♯ E♯ (F) G♯ D♭ D♭ F A♭ D D F♯ A D♯ D♯ F

A♯ E♭ E♭ G B♭ E E G♯ B F F A C F♯ F♯ A♯ C♯ G♭ G♭ B♭ D♭ G G B D G♯ G♯ B♯ (C) D♯ A♭ A♭ C E♭ A A C♯ E A♯ A♯ C

E♯ (F) B♭ B♭ D F B B D♯ F♯

Just intonation

.png)

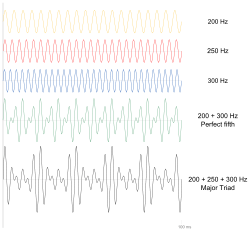

Most Western keyboard instruments are tuned to equal temperament. In equal temperament, each semitone is the same distance apart and there are four semitones between the root and third, three between the third and fifth, and seven between the root and fifth.

Another tuning system that is used is just intonation. In just intonation, a major chord is tuned to the frequency ratio 4:5:6 (![]()

This may be found on I, IV, V, ♭VI, ♭III, and VI.[2] In equal temperament, the fifth is only two cents narrower than the just perfect fifth, but the major third is noticeably different at about 14 cents wider.

Sources

- Kamien, Roger (2008). Music: An Appreciation (6th brief ed.). p. 46. ISBN 978-0-07-340134-8.

- Wright, David (2009). Mathematics and Music. p. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-8218-4873-9.