Added tone chord

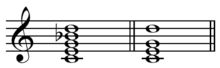

An added tone chord, or added note chord, is a non-tertian chord composed of a tertian triad and an extra "added" note. The added note is not a seventh (three thirds from the chord root), but typically a non-tertian note, which cannot be defined by a sequence of thirds from the root, such as the added sixth (![]()

An added sixth chord ends songs including Hank Williams' "Hey Good Lookin'",[4] Chuck Berry's "Rock and Roll Music",[4] Sam Cooke's "You Send Me",[4] and The Beatles' "She Loves You" (McCartney on 8, Harrison on 6, Lennon on 5).[4] Though the added sixth chord is rarely found inverted, examples include The 5th Dimension's recorded version of "Stoned Soul Picnic" (on 5).[4]

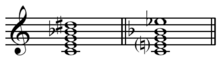

The thirds in a mixed third chord, also split-third chord,[6] a chord that includes as its third both the major and minor third (for a chord on C: C–E♭–E♮–G), are usually separated by an octave or more.[7] While a minor chord placed over a major chord of the same root (creating a tension of ♯9) is somewhat common, a major chord placed over a minor chord of the same root (creating a tension of ♭11) is not as commonplace. Examples of use of the split-third chord include "Rock And Roll Music", Paul McCartney's "Maybe I'm Amazed", and Jimi Hendrix Experience's "Purple Haze" (dominant seventh sharp ninth chord).[5] Tonic dominant seventh chord with split third include Heatwave's "Boogie Nights".[5] It is "suggested" by the final note and chord of "A Hard Day's Night".[5]

Mixed-third chords are frequently encountered as the result of blue notes in blues, country music and rock music; a mixed-third seventh chord (in the form of the minor over the major) is sometimes known among rock guitarists as the "Hendrix chord" (due to its extensive use by rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix).

An example of an added tone chord may be found in Igor Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms[7] while an added tone (G) chord with mixed thirds, a major third and minor third, by William Schuman.[7]

An added tone, such as that added a perfect fifth below the root, may suggest polytonality[7] and the practice of adding tones may have led to superimposing chords and tonalities though added tone chords have most often been used as more intense substitutes for traditional chords.[3] For instance a minor chord that includes a major second interval while still retaining its minor third holds a great deal more dramatic tension due to the very close intervals of the major second and minor third. A major chord with an added major second sounds very distinct from its basic triad counterpart.

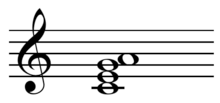

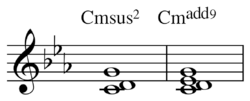

Examples of the added-second chord (notated "add2" or "2" and sometimes "add9") include The Rolling Stones' "You Can't Always Get What You Want", Mr. Mister's "Broken Wings", Don Henley's "The End of the Innocence", The Police's "Every Breath You Take", Cheap Trick's "The Flame", Lionel Richie's "All Night Long (All Night)", Men at Work's "It's a Mistake", DeBarge's "Rhythm of the Night", Starship's "We Built This City", and Deniece Williams' "Let's Hear It for the Boy".[2] Another example is in the verse of The Beatles' "A Hard Day's Night".[5] The jazz rock group Steely Dan popularized a particular voicing of the add2 chord they dubbed the mu chord.

Examples of use of the added-fourth chord, which almost always occurs on the fifth scale degree (notated "add4") thus adding, "the stable tonic pitch", include the second chord in the verse of "Runaway Train" and the introduction of The Who's "Baba O'Riley".[2]

Examples of use of the added-sixth chord (notated "6") include the third measure of The Beatles' "A Hard Day's Night", the second chord of "You Keep Me Hangin' On", the third of "The Eagle And The Hawk", and The Beatles' "She Loves You", being used only occasionally in rock and popular music.[2] When added at the suggestion of Harrison, producer George Martin described the chord as old-fashioned sounding.[2]

See also

Sources

- Hawkins, Stan (Oct 1992). "Prince – Harmonic Analysis of 'Anna Stesia'". Popular Music. 11 (3): 325–335. doi:10.1017/s0261143000005171.

- Stephenson, Ken (2002). What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-300-09239-4.

- Jones, George (1994). HarperCollins College Outline Music Theory, p.50. ISBN 0-06-467168-2.

- Everett, Walter (2009). The Foundations of Rock. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-19-531023-8.

- Stephenson (2002), p.84.

- Kostka & Payne (1995). Tonal Harmony, p.494. Third Edition. ISBN 0-07-035874-5.

- Marquis, G. Welton (1964). Twentieth Century Music Idioms. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc. ISBN 0-313-22624-5.