Mahjar

The Mahjar (Arabic: المهجر, romanized: al-mahjar, one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora"[1]) was a literary movement started by Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to America[2] from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and Palestine[3] at the turn of the 20th century. Like their predecessors in the Nahda movement (or the "Arab Renaissance"), writers of the Mahjar movement were stimulated by their personal encounter with the Western world and participated in the renewal of Arabic literature,[2] hence their proponents being sometimes referred to as writers of the "late Nahda".[4] These writers, in South America as well as the United States, contributed indeed to the development of the Nahda in the early 20th century.[5] Kahlil Gibran is considered to have been the most influential of the "Mahjar poets"[3] or "Mahjari poets".

North America

First periodicals

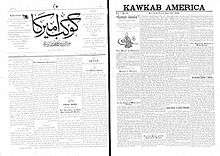

As worded by David Levinson and Melvin Ember, "the drive to sustain some Arab cultural identity" among the immigrant communities in North America "was reinforced from the beginning when educated immigrants launched Arabic-language newspapers and literary societies in both the New York and Boston areas to encourage poetry and writing, with the aim of keeping alive and enriching the Arabic cultural heritage."[6] Thus, in 1892, the first American Arabic-language newspaper, Kawkab America, was founded in New York and continued until 1908, and the first Arabic-language magazine Al-Funoon was published by Nasib Arida in New York from 1913 to 1918. This magazine served as a mouthpiece for young Mahjari writers.

The Pen League

The Pen League (Arabic: الرابطة القلمية / ALA-LC: al-rābiṭah al-qalamīyah) was the first[7] Arabic-language literary society in North America, formed initially by Nasib Arida and Abd al-Masih Haddad[8] in 1915[9] or 1916,[10] and subsequently re-formed in 1920 by a larger group of Mahjari writers in New York led by Kahlil Gibran.[11] They had been working closely since 1911.[12] The league dissolved following Gibran's death in 1931 and Mikhail Naimy's return to Lebanon in 1932.[13]

The primary goals of the Pen League were, in Naimy's words as Secretary, "to lift Arabic literature from the quagmire of stagnation and imitation, and to infuse a new life into its veins so as to make of it an active force in the building up of the Arab nations".[14] As Naimy expressed in the by-laws he drew up for the group:

The tendency to keep our language and literature within the narrow bounds of aping the ancients in form and substance is a most pernicious tendency; if left unopposed, it will soon lead to decay and disintegration... To imitate them is a deadly shame... We must be true to ourselves if we would be true to our ancestors.[15]

Literary historian Nadeem Naimy assesses the group's importance as having shifted the criteria of aesthetic merit in Arabic literature:

Focusing on Man rather than on language, on the human rather than on the law and on the spirit rather than on the letter, the Mahjar (Arab emigrant) School is said to have ushered Arabic literature from its age old classicism into the modern era.[16]

Members of the Pen League included: Nasib Arida, Rashid Ayyub, Wadi Bahout, William Catzeflis (or Katsiflis), Kahlil Gibran (Chairman), Abd al-Masih Haddad, Nadra Haddad, Elia Abu Madi, Mikhail Naimy (Secretary), and Ameen Rihani.[17] Musicians such as Russell Bunai were also associated with the group.[18]

South America

The first Arabic-language newspaper in Brazil, Al-Faiáh (Arabic: الفيحاء / ALA-LC: al-fayḥāʾ), appeared in Campinas in November 1895, followed by Al-Brasil (Arabic: البرازيل / ALA-LC: al-brāzīl) in Santos less than six months later.[19] The two merged a year later in São Paulo.[19] The first Arabic-language literary circle in South America, Riwaq al-Ma'arri, was founded in 1900[20] by Sa'id Abu Hamza, who was also settled in São Paulo.[21]

Shafiq al-Ma'luf "led the major grouping of South American Mahjar poets".[22]

Principles

Mikhail Naimy's book of literary criticism Al-Ghirbal (published in 1923) contains the main principles of the Mahjar movement.[23]

References

- Hans Wehr. Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic (4th ed.). p. 1195.

- Archipel (in French). p. 66.

Les écrivains du Mahjar sont les écrivains de langue arabe ayant émigré en Amérique. Comme leurs aînés de la Nahda, ils sont stimulés par leur rencontre personnelle de l'Occident et participent largement au renouvellement de la littérature arabe.

- Feathers and the Horizon.

- Arabic Thought beyond the Liberal Age. p. 179.

- Somekh, "The Neo-Classical Poets" in M.M. Badawi (ed.) "Modern Arabic Literature", Cambridge University Press 1992, pp36-82

- Levinson, David; Ember, Elvin (1997). American immigrant cultures: builders of a nation. Simon & Schuster Macmillan. p. 864. ISBN 978-0-02-897213-8.

- Zéghidour, Slimane (1982). La poésie arabe moderne entre l'Islam et l'Occident. KARTHALA Editions. p. 142. ISBN 978-2-86537-047-4.

- "Al-Rabitah al-Qalamiyah (1916, 1920-1931)". al-Funun. Nasib Aridah Organization. Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- Haiek, Joseph R. (1984). Arab-American almanac. News Circle Publishing House. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-915652-21-1.

- Popp, Richard Alan (2001). "Al-Rābiṭah al-Qalamīyah, 1916". Journal of Arabic Literature. Brill. 32 (1): 30–52. doi:10.1163/157006401X00123. JSTOR 4183426.

- Katibah, Habib Ibrahim; Farhat Jacob Ziadeh (1946). Arabic-speaking Americans. Institute of Arab American Affairs. p. 13. OCLC 2794438.

- Nijland, Cornelis (2001). "Religious motifs and themes in North American Mahjar poetry". In Gert Borg, Ed de Moor (ed.). Representations of the divine in Arabic poetry. Rodopi. p. 161. ISBN 978-90-420-1574-6.

- Starkey, Paul (2006). Modern Arabic literature. Edinburgh University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7486-1290-1.

- Naimy, Mikhail (1950). Khalil [sic] Gibran. p. 50., qtd. by Nadeem Naimy in The Lebanese Prophets of New York, American University of Beirut, 1985, p. 18.

- Naimy, Mikhail (1950). Kahlil [sic] Gibran. p. 156., qtd. by Nadeem Naimy in The Lebanese Prophets of New York, American University of Beirut, 1985, pp. 18-18.

- Naimy, Nadeem (1985). The Lebanese Prophets of New York. American University of Beirut. p. 8.

- Benson, Kathleen; Philip M. Kayal (2002). A community of many worlds: Arab Americans in New York City. Syracuse University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8156-0739-7.

- Zuhur, Sherifa (1998). Images of enchantment: visual and performing arts of the Middle East. American University in Cairo Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-977-424-467-4.

- Jeff Lesser. Negotiating national identity: immigrants, minorities, and the struggle for ethnicity in Brazil. p. 53.

- Paul Starkey. Modern Arabic Literature. p. 62.

- Cultures. p. 155.

- Feathers and the Horizon. p. 216.

- M. M. Badawi (1970). An Anthology of Modern Arabic Verse. Oxford University Press.