Magnetized Liner Inertial Fusion

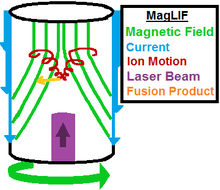

Magnetized Liner Inertial Fusion (MagLIF) is an emerging method of producing controlled nuclear fusion. It is part of the broad category of inertial fusion energy (IFE) systems, which uses the inward movement of the fusion fuel to reach densities and temperatures where fusion reactions take place. Previous IFE experiments used laser drivers to reach these conditions, whereas MagLIF uses a combination of lasers for heating and Z-pinch for compression. A variety of theoretical considerations suggest such a system will reach the required conditions for fusion with a machine of significantly less complexity than the pure-laser approach.

Description

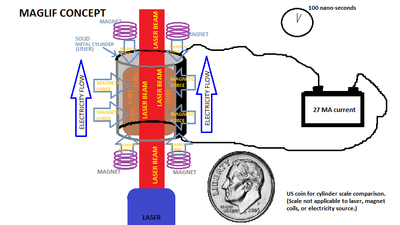

MagLIF is a method of generating energy by using a 100 nanosecond pulse of electricity to create an intense Z-pinch magnetic field that inwardly crushes a fuel filled cylindrical metal liner (a hohlraum) through which the electric pulse runs. Just before the cylinder implodes, a laser is used to preheat fusion fuel (such as deuterium-tritium) that is held within the cylinder and contained by a magnetic field. Sandia National Labs is currently exploring the potential for this method to generate energy by utilizing the Z machine.

MagLIF has characteristics of both Inertial confinement fusion (due to the usage of a laser and pulsed compression) and magnetic confinement (due to the utilization of a powerful magnetic field to inhibit thermal conduction and contain the plasma). In results published in 2012, a LASNEX based computer simulation of a 70 megaampere facility showed the prospect of a spectacular energy return of 1000 times the expended energy. A 60 MA facility would produce a 100x yield. The currently available facility at Sandia, Z machine, is capable of 27 MA and may be capable of producing slightly more than breakeven energy while helping to validate the computer simulations.[1] The Z-machine conducted MagLIF experiments in November 2013 with a view towards breakeven experiments using D-T fuel in 2018.[2]

Sandia Labs planned to proceed to ignition experiments after establishing the following:[3]

- That the liner will not break apart too quickly under the intense energy. This has been apparently confirmed by recent experiments. This hurdle was the biggest concern regarding MagLIF following its initial proposal.

- That laser preheating is able to correctly heat the fuel — to be confirmed by experiments starting in December 2012.

- That magnetic fields generated by a pair of coils above and below the hohlraum can serve to trap the preheated fusion fuel and importantly inhibit thermal conduction without causing the target to buckle prematurely. — to be confirmed by experiments starting in December 2012.

Following these experiments, an integrated test started in November 2013. The test yielded about 1010 high-energy neutrons.

As of November 2013, the facility at Sandia labs had the following capabilities:[2][4]

- 10 tesla magnetic field

- 2 kJ laser

- 16 MA

- D-D fuel

In 2014, the test yielded up to 2×1012 D-D neutrons under the following conditions:[5]

- 10 tesla magnetic field

- 2.5 kJ laser

- 19 MA

- D-D fuel

Experiments aiming for energy breakeven with D-T fuel were expected to occur in 2018.[6]

To achieve scientific breakeven, the facility is going through a 5-year upgrade to:

- 30 teslas

- 8 kJ laser

- 27 MA

- D-T fuel handling[2]

In 2019, after encountering significant problems related to mixing of imploding foil with fuel and helical instability of plasma,[7] the tests yielded up to 3.2×1012 neutrons under the following conditions:[8]

- 1.2 kJ laser

- 18 MA

References

- Slutz, Stephen; Roger A. Vesey (12 January 2012). "High-Gain Magnetized Inertial Fusion". Physical Review Letters. 108 (2): 025003. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.108b5003S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.025003. PMID 22324693.

- Gibbs WW (2014). "Triple-threat method sparks hope for fusion". Nature. 505 (7481): 9–10. Bibcode:2014Natur.505....9G. doi:10.1038/505009a. PMID 24380935.

- "Dry-Run Experiments Verify Key Aspect of Nuclear Fusion Concept: Scientific 'Break-Even' or Better Is Near-Term Goal". Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- Ryan, McBride. "Magnetized LIF and Cylindrical Dynamic Materials Properties Experiments on Z". Krell Institute. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- Gomez, M. R.; et al. "Experimental Verification of the Magnetized Liner Inertial Fusion (MagLIF) Concept". Krell Institute. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- Cuneo, M.E.; et al. (2012). "Magnetically Driven Implosions for Inertial Confinement Fusion at Sandia National Laboratories". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science. 40 (12): 3222–3245. Bibcode:2012ITPS...40.3222C. doi:10.1109/TPS.2012.2223488.

- Seyler, C.E.; Martin, M.R.; Hamlin, N.D. (2018). "Helical instability in MagLIF due to axial flux compression by low-density plasma". Physics of Plasmas. Physics of Plasmas 25, 062711 (2018). 25 (6): 062711. Bibcode:2018PhPl...25f2711S. doi:10.1063/1.5028365. OSTI 1456307.

- Gomez, M. R.; et al. (2019). "Assessing Stagnation Conditions and Identifying Trends in Magnetized Liner Inertial Fusion". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science vol. 47/5. 47 (5): 2081–2101. Bibcode:2019ITPS...47.2081G. doi:10.1109/TPS.2019.2893517. OSTI 1529761.