Madonna of the Dry Tree

Madonna of the Dry Tree (or Our Lady of the Barren Tree) is a small oil-on-oak panel painting dated c. 1462–1465 by the Early Netherlandish painter Petrus Christus. Unusually innovative and dramatic, it presents the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child while standing on a disembodied dead tree trunk and surrounded by a crown of thorns.

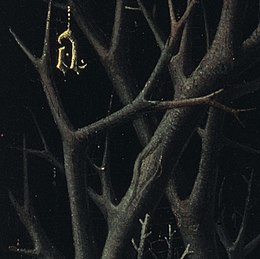

The painting's imagery is thought to be derive from the Book of Ezekiel, with the dry tree a symbol of the withered Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden, brought to life by the Virgin and the birth of Christ. The 15 golden "A"s hanging from the branches of the tree represent the first letter of the Angelic Salutation, the Ave Maria.[1] The Christ Child holds an orb crowned with a cross. The iconography may draw from the Confraternity of Our Lady of the Dry Tree in Bruges, to which both Christus and his wife Gaudicine belonged.

Description

Mary is shown holding the Christ child in her arms. She is surrounded by thin, barren, branches, that reach around her to an oval arch.[2] She wears long red robe with green lining, The folds of her dress cut into the form in an almost sculptural manner. Her robe closely resembles the dress in Christus's c. 1444 Exeter Madonna,[3] leading to speculation that the painting was completed earlier than the usually assumed 1462–1465. Unusually for a Madonna of the time, her face is unidealised; her features are not soft nor rounded, and her expression less presupposing than in Christus's later Madonnas or even secular female portraits.[4] Joel Upton writes of her that "she is shown as a warm and human figure, very attractive, and yet serene and demure as the Mother of God."[2]

The representation of Christ seems derived from Rogier van der Weyden, especially in the playfulness and amiability of his facial expression, although given that Christus might not have had access to the older master's work, the influence may be second-hand, probably through the paintings of Hans Memling. The panel is highly illustionistic, perhaps on par with the older painter's Durán Madonna. Christus employs trompe-l'œil techniques in a number of passages, creating a three-dimensional effect that adds to the strangeness and disembodied atmosphere. These can be most notably seen in the Virgin's hand as it lies below the child's toes, in the orb held in his hands, and in the golden letters hanging from the tree briars.[3]

X-radiography reveals little preparatory underdrawing outside of a series of ruled lines used to situate elements within the overall design. Maryan Ainsworth notes that this is typical of Christus's smaller panels, some which – including this work – could be considered miniatures, and compares it to the techniques used in contemporary illuminated manuscripts.[5]

Our Lady of the Dry Tree

Art historian Grete Ring connected the iconography to the Bruges confraternity of "Our Lady of the Dry Tree".[7] Christus joined the "Confraternity of Our Lady of the Dry Tree" sometime around 1462–63.[8][lower-alpha 1] Both confraternities were patronized by members of the upper echelon of Burgundian society; Philip the Good's wife Isabella of Portugal, as well as most of the leading Burgundian nobles, upper-class families and foreign traders of Bruges, such as the Portinaris.[9] Christus joined – for the same reason Gerard David would some years later – to attract wealthy patrons.[9]

Philip the Good is believed to have established the confraternity after a successful battle against the French. Beforehand, he is said to have prayed to an image of the Virgin carved on a dry tree. Although the confraternity already existed, the story reveals the veneration of images of the Virgin carved on trees.[10] The tradition of Marian images on trees, either suspended or carved, was a blend of pagan and Christian worship originating as early as the fifth century. Such trees were commonly found in crossroads, functioning as landscape markers. Our Lady of the Oak and Our Lady of the Cherry are others in the same tradition.[11]

It was first documented in 1396, but had probably been established earlier. Records show the Confraternity met in a private chapel,[12] located in the Church of the Minorites (or Franciscans) which was destroyed during the Netherlandish Reformation in 1578.[7]

Iconography

The work's iconography is both dramatic and highly unusual, and was described by Ainsworth as unprecedented in Netherlandish painting. The imagery may be derived from Ezekiel 17:24: "…and all the trees of the field shall know that I the Lord have brought down the high tree, have exalted the low tree, have dried up the green tree, and have made the dry tree to flourish".[1]

The painting seems to be a somewhat bitter representation of the "Tree of Knowledge", but wilted and thorny. Art historians presume it represents a metaphor for original sin, and that presumably the tree will not return to life until the coming of Christ. The tree received a green graft from the Tree of Knowledge, wrote medieval philosopher Guillaume de Deguileville in his Le Pèlerinage de l'Âme (The Pilgrimage of the Soul), metaphorically reflected in the birth of the Virgin to a barren mother.[1]

The 15 letter A's hanging from the tree are generally seen as abbreviations for Ave, or Ave Maria. Their number may to be an allusion to the 150 "Hail Marys" recited in then-contemporary versions of the rosary, although this form of devotion did not become popular until 1475, some ten years after Christus' panel.[13] Two other interpretations for the A's have been put forth. One is that they symbolize arbor or arbore, as other similar devotional works show the trees in an arbor. Hugo van der Velden suggests the possibility that the piece might have been commissioned by a member of the confraternity, Anselme Adornes, whose interest in devotional work is evidenced by his possession of van Eyck's Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata.[14]

Influences and provenance

The panel influenced Peter Claeyssens the Younger's 1620 triptych Our Lady of the Dry Tree, which drew from the same sources and is equally dark in tone and theme, but lacks the dramatic impact of Christus' panel.[12]

The painting was first recorded in a private collection in Belgium before 1919. It was acquired by the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid in 1965.[1]

Notes

- Christus and his wife were listed as members in 1462; in 1463 they appeared on the list of new members. See Sterling (1971), 19; and Hand (1987), 41

Citations

- Ainsworth (1994), 162

- Upton (1990), 60

- Ainsworth (1994), 164

- Ainsworth (1994), 161

- Ainsworth (1994), 103; 115

- van der Velden, 98

- Borobia, Mar. "The Virgin of the dry Treeca. 1465". Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. Retrieved 2 August 2020

- Sterling (1971), 19

- Ainsworth (1998), 34

- van der Velden, 95

- van der Velden, 98-99

- van der Velden, 91

- van der Velden, 108

- van der Velden, 109

Sources

- Ainsworth, Maryan. Petrus Christus: Renaissance Master of Bruges. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994. ISBN 0-8109-6482-1

- Ainsworth, Maryan. "The Business of Art: Patrons, Clients and Art Markets". Maryan Ainsworth, et al. (eds.) From Van Eyck to Bruegel: Early Netherlandish Painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998. ISBN 0-87099-871-4.

- Hand, John Oliver; Martha Wolff. Early Netherlandish Painting. Washington: National Gallery of Art, (1987). ISBN 978-0-89468-093-9

- Kren, Scott; McKendrick, Scot; Ainsworth, Maryan; Moodey, Elizabeth J. "Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting". Renaissance Quarterly. Vol. 57, No. 3 (Autumn, 2004), pp. 1032-1033

- Sterling, Charles. "Observations on Petrus Christus". The Art Bulletin, Vol. 53, No. 1. March 1971

- Van der Velden, Hugo. "Petrus Christus's Our Lady of the Dry Tree". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Volume 60, 1997.

- Upton, Joel Morgan. Petrus Christus: His Place in Fifteenth-Century Flemish Painting. Penn State Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0-2710-4-2862