Macon, Mississippi

Macon is a city in Noxubee County, Mississippi along the Noxubee River. The population was 2,768 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Noxubee County.[3]

Macon, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

Noxubee County Courthouse in Macon | |

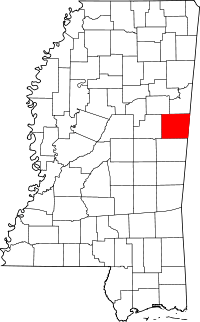

Location of Macon, Mississippi | |

Macon, Mississippi Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 33°6′45″N 88°33′40″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Noxubee |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.85 sq mi (9.98 km2) |

| • Land | 3.83 sq mi (9.92 km2) |

| • Water | 0.02 sq mi (0.06 km2) |

| Elevation | 197 ft (60 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 2,768 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 2,421 |

| • Density | 632.28/sq mi (244.11/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 39341 |

| Area code(s) | 662 |

| FIPS code | 28-44240 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0673046 |

| Website | www |

History

In 1817 the Jackson Military Road was built at the urging of Andrew Jackson to provide a direct connection between Nashville and New Orleans. The road crossed the Noxubee River just west of Macon, located at the old Choctaw village of Taladega, now the site of the local golf club. The road declined in importance in the 1840s, largely due to the difficulty of travel in the swamps surrounding the Noxubee River in and west of Macon.

The route for the most part was replaced by the Robinson Road, which ran through Agency and Louisville before joining the Natchez Trace, bypassing Macon.[4]

On September 15, 1830, US government officials met with an audience of 6,000 Choctaw men, women and children at Dancing Rabbit Creek to explain the policy of removal through interpreters. The Choctaws faced migration west of the Mississippi River or submitting to U.S. and state law as citizens.[5]

The treaty would sign away the remaining traditional homeland to the United States; however, a provision in the treaty made removal more acceptable.[6]

The town was named Macon on August 10, 1835 in honor of Nathaniel Macon, a statesman from North Carolina.[7]

The city served as the capital for the state of Mississippi during the Civil War from 1863 onward.[8]

The legislature was housed in the Calhoun Institute, which also housed Governor Charles Clark's office and served as one of several hospital sites in Macon.[9]

In October 1865, Governor Benjamin Humphreys attempted to retrieve the furniture from the governor's mansion to Jackson, however it had been either destroyed or stolen.[10]

Lynchings

- In 1871, William Coleman, a black Macon resident who allegedly failed to tip his hat to a white man, was shot, beaten, stabbed, whipped, and left for dead by the Ku Klux Klan. Coleman survived and later testified about his ordeal before congress.[11]

- On January 1, 1898, James Jones was lynched in Macon.

- On June 30, 1898, Henry Williams, was lynched in Macon, after being accused of rape.

- On February 18, 1901, Fred Isham and Henry Isham were lynched in Macon.[12]

- On May 4, 1912, George Somerville was taken from the sheriff and hanged by a mob for an alleged shooting.[13]

- On May 7, 1912, G.W. Edd was lynched[14]

- On May 12, 1927, Dan Anderson was lynched in Macon.[15]

- On June 27, 1919, in an incident described as part of the Red Summer, a mob of white citizens including a banker and a deputy sheriff, among many others, attacked prominent black citizens.[16]

- In May 1929, Steven Jenkins was killed by a mob of white citizens. No legal action was considered.[17]

In 2016, Macon was the poorest town (1,000–3,000 population) in the United States.[18]

The Noxubee County library is located in Macon. The building, which was constructed as a jail in 1907, still contains a gallows.[19]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 1.5 square miles (3.9 km2), all land.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 989 | — | |

| 1870 | 975 | −1.4% | |

| 1880 | 2,074 | 112.7% | |

| 1890 | 1,565 | −24.5% | |

| 1900 | 2,067 | 32.1% | |

| 1910 | 2,024 | −2.1% | |

| 1920 | 2,051 | 1.3% | |

| 1930 | 2,198 | 7.2% | |

| 1940 | 2,261 | 2.9% | |

| 1950 | 2,241 | −0.9% | |

| 1960 | 2,432 | 8.5% | |

| 1970 | 2,612 | 7.4% | |

| 1980 | 2,396 | −8.3% | |

| 1990 | 2,256 | −5.8% | |

| 2000 | 2,461 | 9.1% | |

| 2010 | 2,768 | 12.5% | |

| Est. 2019 | 2,421 | [2] | −12.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[20] | |||

As of the census[21] of 2000, there were 2,461 people, 906 households, and 587 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,624.8 people per square mile (629.3/km2). There were 1,015 housing units at an average density of 670.1 per square mile (259.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 31.49% White, 67.33% African American, 0.20% Native American, 0.41% Asian, 0.08% from other races, and 0.49% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.41% of the population.

There were 906 households, out of which 32.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 34.0% were married couples living together, 27.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.1% were non-families. 33.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.53 and the average family size was 3.25.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 28.9% under the age of 18, 10.3% from 18 to 24, 27.8% from 25 to 44, 16.2% from 45 to 64, and 16.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 82.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 80.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $20,800, and the median income for a family was $26,696. Males had a median income of $22,969 versus $16,898 for females. The per capita income for the city was $12,568. About 29.2% of families and 36.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 50.3% of those under age 18 and 21.8% of those age 65 or over.

Notable people

- Larry Anderson, basketball coach for MIT[22]

- Buster Barnett, former NFL player for the Buffalo Bills

- Carey Bell, blues harmonicist

- Cornelius Cash, basketball player

- Darion Conner, former professional football player with the Atlanta Falcons

- Willie Daniel, NFL football player

- Jesse Fortune, blues singer

- Victoria Clay Haley, suffragist

- Nate Hughes, former professional football player with Jacksonville Jaguars, and Detroit Lions[23]

- Stephen D. Lee, confederate general, slaveholder, farmed the Devereaux plantation for ten years.

- Samuel Pandolfo, businessman

- America W. Robinson, African American educator; contralto (Fisk Jubilee Singers)

- Deontae Skinner, NFL player

- Purvis Short, former professional basketball player

- Nate Wayne, former NFL football player with Green Bay Packers, Denver Broncos, and Philadelphia Eagles

- Israel Victor Welch, Confederate politician and lawyer lived in Macon after the war

- Margaret Murray Washington, educator; wife of Booker T. Washington

- Ben Ames Williams, novelist

Education

Historically, the city of Macon had the largest schools in Noxubee County, including Macon High School (Mississippi). In 1917, the city proposed consolidation of the school district with Noxubee County, with the goal of replacing the single-teacher system prevalent throughout the county.[24]

The City of Macon is now served by the Noxubee County School District. East Mississippi Community College offers some courses at Noxubee County High School in Macon.[25]

When federal courts mandated integration of the public schools, a segregation academy, Central Academy, was built in Macon, secretly using public school funds to construct the private school.[26] White student enrollment in public schools dropped from 829 to 71 during this period.[27] Attendance at Central Academy eventually dwindled to 51 students, resulting in the shuttering of the school following the 2017 school year.[28]

Media

The first newspaper in Macon was the Macon intelligencer, which operated from 1838–1840. Another paper, the Macon Herald ran from 1841–1842.[29] The Macon Beacon was established in 1849.[30] It served Macon as a daily from 1859–1995.[31] It continues to operate as a weekly, published on Thursdays.[32] There is a local radio station, WPEZ 93.7 FM.

Sports

The Noxubee County High School football and basketball teams compete in District 4A. The football team won the 2009 and 2012 State Championship. The Noxubee High School Tigers girls basketball team won back to back state titles in 1993–94.

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- Love, William A., "General Jackson's Military Road," Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society Vol. XI (1910), pp. 403-17; accessed November 11, 2014.

- Remini, Robert. ""Brothers, Listen ... You Must Submit"". Andrew Jackson. History Book Club. p. 272. ISBN 0-9650631-0-7.

- Green, Len (October 1978). "Choctaw Treaties". Bishinik. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- "Formation of Noxubee County: Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek". Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- "Mississippi". Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- "History of City of Macon & Noxubee County". Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- Lohrenz, Mary (November 17, 2010). "Governor's Mansion during the Civil War". Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- Waldrep, Christopher (2009). African Americans Confront Lynching. pp. 137–38. ISBN 978-0742552739.

- "Over 3000 Lynchings in Twenty Years". The St Paul and Minneapolis Appeal. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- "Mr. Thos. Dee and Son Shot Sheriff Dantzler's Dogs Chase the Right Negro, who was captured". The Macon Beacon. May 10, 1912. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- "A Memorial to the Victims of Lynching". America's Black Holocaust Museum. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- "The 1898 Lynching Report - HistoricalCrimeDetective.com". www.historicalcrimedetective.com.

- Dadabo, Elizabeth. Historical Moments of Policing, Violence, and Resistance Series Volume 6 Chicago’s Red Summer of 1919.

- "Macon Lynching Closed Affair, Sheriff Avers". The Greenwood Commonwealth. Greenwood, Mississippi. May 13, 1929. Retrieved 23 March 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- Lauterbach, Cole (June 29, 2018). "America's poorest city is in Illinois". Illinois News Network.

- Benton, Charlie (October 31, 2019). "Hanging onto history: Noxubee librarian discusses 1907 building's unusual feature". Starkville Daily News.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Cleveland, Rick (June 4, 2019). "From Macon to MIT: Larry Anderson's Amazing Story". Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- "Nate Hughes". NFL Enterprises. Retrieved November 23, 2014.

- "Better School Opportunities for Macon and Surrounding Country". Macon Beacon. June 1, 1907. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- CATALOG 2007-09, East Mississippi Community College Archived 2010-12-18 at the Wayback Machine, eastms.edu; retrieved March 1, 2011.

- "Schools board member resigns before NAACP asks". Clarksdale Press-Register. May 19, 1982. p. 11.

- Swartz, David R (October 19, 2004). "October 2004 Swartz". Goshen College. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- Lamphin, Eric (April 20, 2017). "VIDEO: MACON'S CENTRAL ACADEMY CLOSING DOWN". WCBI. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- "Results: Digitized Newspapers « Chronicling America « Library of Congress". chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.

- "History of City of Macon & Noxubee County". Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- "Macon beacon: (Macon, Miss.) 1859-1995". Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- "Macon". Retrieved December 18, 2017.