Macedonian Mule Corps

The Macedonian Mule Corps (Greek: Μακεδονικόν Μεταγωγικόν Σώμα) was a formation of the British Salonika Army consisting primarily of Cypriot muleteers and their mules. The unit was established in 1916 and dissolved in March 1919, during its service it provided crucial logistical support to the Allied war effort on the Macedonian front. 12,288 Cypriots served in the corps, 3,000 of whom received bronze British War Medals.

| Macedonian Mule Corps | |

|---|---|

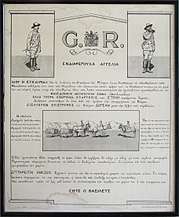

Poster urging Cypriots to enlist in the Macedonian Mule Corps | |

| Active | 1916–1919 |

| Country | British Cyprus |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Army |

| Role | Labor |

| Size | 12,288 |

| Engagements | World War I |

Background

At the outbreak of the First World War Cyprus was nominally a part of the Ottoman Empire, while in fact being administered by the British Empire as agreed in the Cyprus Convention of 1878. On 5 November 1914, the Ottomans entered the conflict on the side of the Central Powers, prompting Britain to void the Cyprus Convention and annex the island as the two states were now at war. A number of security measures including telegraph censorship and martial law were introduced although Cyprus remained relatively isolated from the Macedonian front, Gallipoli Campaign, Sinai and Palestine Campaigns. As it did not possess harbors large enough to accommodate large warships, local authorities shifted their focus to supplying the fronts in its periphery with food as well as housing those wounded in actions, prisoners of war as well as refugees.[1]

During the course of the Crimean War (1853–1856) French merchants had acquired mules from the island for the needs of the French expeditionary force. By the time of the British occupation of the island Cypriot mules had already cemented their reputation as both sturdy pack animals and an alternative to polo ponies. Cypriot mules were later purchased during Greek army mobilization of 1880, and the Mahdist War by the British themselves who also recruited local muleteers. Starting from the middle of the 1880s Cypriot mules were exported to India. In 1902, 128 mules were dispatched to South Africa in support of the British forces fighting in the Second Boer War. In December 1910, the Cypriot Breeding Committee began importing horses and mules from the Middle East in order to improve the quality of the local breeds. British General Staff reports dating to 1907 and 1913 respectively described the Cypriot mules as particularly docile and adapted to mountain warfare.

Service

%2C_item_3.jpg)

On 24 April 1916, the commander of the British Salonika Army Bryan Mahon stated that for his advance towards the Greco–Serbian frontier to succeed, the recruitment of 1,676 pack animals and 1,232 muleteers per division was needed. Macedonia's rough terrain, limited infrastructure and an underdeveloped railway network, necessitated the use of pack animals for military logistics.[4] On 24 May, British ambassador to Greece Francis Elliot requested the high commissioner of Cyprus John Eugene Clauson to raise a force of 7,000 Cypriot muleteers to Macedonian Front in order to augment the British Salonika Army. Three days later the British H.Q. in Salonika sent another inquiry, urgently requesting 3,000 Cypriot muleteers. The National Schism in the then neutral Greece had frustrated British efforts to recruit locals from among the pro–Triple Entente faction. With the Greek prime minister Eleftherios Venizelos stating that he could not guarantee that the British would be allowed to continue their recruitment drive. On 24 June, a belated reply from the British War Office ordered Clauson to purchase 2,000 mules and recruit 500 men to command them, this period of inaction drew the criticism of the Colonial Office. On 25 July, the first group of 150 muleteers disembarked at Salonika. On 27 July, 3,000 additional Cypriot muleteers (with a ratio of 1 foreman per 20 muleteers) were urgently solicited for the Macedonian Front. In the meantime a Mule Purchasing Commission had been established in Famagusta under the supervision of Major L. Sisman. On 2 August, 796 muleteers arrived at Salonika, 500 joining the XII Corps and 196 the XVI Corps.

On 14 August, Clauson issued an order concerning the mandatory requisitioning mules for military purposes under martial law. From July until November, 2,750 mules, 1,200 donkeys and 140 ponies were sent to Salonica. By July 1919, over 3,500 mules and 3,000 donkeys had been exported. On 18 October, special legislation banned immigration for Cypriot males of conscription age in order to halt the mass migration of Cypriots to the USA. Passports that were already issued were subsequently revoked. A number of rudimentary recruitment posters and leaflets were issued starting from the summer of 1916, the posters were issued in English, Greek and Turkish. Those interested were invited to the recruitment camps situated at Paphos, Limassol, Nicosia, Kyrenia and Famagusta. As of 6 November, 3,496 Cypriots had joined the corps in the capacity of muleteers, foremen and interpreters. The ranks of the Macedonian Mule Corps personnel were distinguished by an arm brassard bearing the letters "MMC" and a cap badge. Recruits underwent 15 days of basic training while in Cyprus and were provided further mule and weapons training upon arriving in Salonica. Although officially muleteers were unarmed, a MMC veteran claimed that they were given Lee–Enfield rifles for the purpose of self defense.[8] A crucial factor in the drive's success was the high wages (90 drachmas per month[9]), free food and clothing offered, as well as the fact that the muleteers were registered as camp followers under the Army Act, a statement that later triggered controversy over the compensation of those killed and injured. In July 1917, the Mule Purchasing Commission was renamed into Muleteer Recruiting and Staff Purchasing Commission, shifting its focus towards the recruiting manpower. During the course of the campaign Cypriot muleteers were tasked with transporting food, weapons, ammunition and water to the front as well as carrying injured soldiers back and working on road construction. The animals and their handlers endured harsh conditions, such as navigating swamps, rivers and mountain terrain during the night and under freezing temperatures.

Aftermath

The Corps were dissolved in March 1919, by that time 12,288 men had served in the unit or approximately 20% of the Cypriot male population between the ages of 18 and 39. The Corps played a crucial role in the logistics of the British and French armies on the Macedonian Front, contributing to the eventual Allied victory. Following the end of military operations the Cypriots were stationed at Varna, Gallipoli, Istanbul, Serres, Doiran, Serbia and other locales. The veterans of the Macedonian Mule Corps received 3,000 bronze British War Medals.[14] At the conclusion of the war most of the mules were sold to Macedonian civilians, although some were shipped to Egypt and later on to Anton Denikin's Anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army which was at the time fighting in the Russian Civil War.

See also

Footnotes

- Heraclidou 2014, pp. 193–194.

- Çetiner 2017, p. 353.

- Çetiner 2017, pp. 361-362.

- Çetiner 2017, p. 359.

- Heraclidou 2014, p. 196.

References

- Çetiner, Nur (2017). "The Identity Conflict of the Cypriots: Cypriot Mule Corps in the First World War". The Journal of International Social Research. 10 (52): 352–365. doi:10.17719/jisr.2017.1898. Retrieved 8 May 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heraclidou, Antigone (2014). "Cyprus's Non-military Contribution to the Allied War Effort during World War I". The Round Table. 103 (2): 193–200. doi:10.1080/00358533.2014.898502.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Varnava, Andrekos (2014). "Recruitment and Volunteerism for the Cypriot Mule Corps, 1916-1919. Pushed or Pulled?". Itinerario. 38 (3): 79–101. doi:10.1017/S0165115314000540. Retrieved 8 May 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Varnava, Andrekos (2016). "Fighting Asses: British Procurement of Cypriot Mules and Their Condition and Treatment in Macedonia". War in History. 23 (4): 489–515. doi:10.1177/0968344515585400.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)