MV TransAtlantic

MV TransAtlantic is a U.S.-flagged container ship owned and operated by TransAtlantic Lines LLC. The 100-metre (330 ft) long ship was built at Wuhu Shipyard in Wuhu, China in 1997 as Steamers Future. Originally owned by Singapore's Keppel Corporation, she has had three owners, been registered under three flags, and been renamed ten times.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: |

|

| Owner: | TransAtlantic Lines LLC[1] |

| Operator: | TransAtlantic Lines LLC[1] |

| Port of registry: | New York[1] |

| Identification: |

|

| Status: | In service[2] |

| Name: | Baffin Strait |

| Owner: | Rehder & Arkon |

| Port of registry: | Antigua and Barbuda[3] |

| Identification: | IMO number: 9148520 |

| Name: | 2001–2004 Steamers Future,[4] 2000–2001 Stl Future,[4] 2000–2000 Steamers Future,[4] 1998–2000 Mekong Star,[4] 1998–1998 Steamers Future,[4] 1997–1998 Eagle Faith,[4] 1997–1997 Steamers Future.[4] |

| Owner: | Keppel Corporation |

| Operator: | Keppel Corporation |

| Port of registry: | Singapore[3] |

| Builder: | Wuhu Xinlian Shipbuilding Co. Ltd.[5] |

| Laid down: | 8 February 1996[5] |

| Launched: | 28 May 1996[5] |

| Completed: | 25 February 1997[5] |

| Identification: | IMO number: 9148520 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: |

|

| Tonnage: | 4,276 GT[1] |

| Displacement: | 8,299 long tons[7] |

| Length: | 100.59 m (330.0 ft)[8] |

| Beam: | 16.24 m (53.3 ft)[8] |

| Draft: | 8.2 m (26.9 ft)[8] |

| Installed power: | 3 Wärtsilä UD25L655D diesels[9] |

| Propulsion: | Wärtsilä 9F32E diesel,[10] controllable-pitch propeller,[9] tunnel-type bow thruster.[9] |

| Speed: | 13 kts[10] |

| Capacity: |

|

| Crew: | 13[10] |

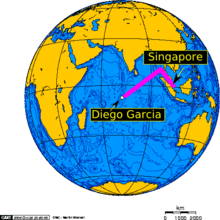

From 2004 to 2009, the ship, under the name Baffin Strait (T-AK W9519), was one of Military Sealift Command's seven chartered container ships, and delivered 250 containers every month from Singapore to Diego Garcia.[10][12] During this charter, she carried everything from fresh food to building supplies to aircraft parts, delivering more than 200,000 tons of cargo to the island each year.[12]

After finishing the Diego Garcia contract, the ship sailed from Singapore on 19 November 2009 for a shipyard period in Wilmington, North Carolina by way of the Suez Canal. In May 2010, she was towed to Ciramar Shipyard in the Dominican Republic for more extensive repairs.

Construction

Then named Steamer's Future, the ship's keel was laid on 8 February 1996 at Wuhu Shipyard in Wuhu, China.[4][5] Its hull, constructed from ordinary strength steel,[13] has an overall length of 100.59 metres (330.0 ft).[8] In terms of width, the ship has a beam of 16.24 metres (53.3 ft). The height from the top of the keel to the main deck, called the moulded depth, is 8.2 metres (27 ft).[8][14]

Although much of its career has been spent crossing oceans, the ship's container-carrying capacity of 384 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU) (384 20-foot shipping containers) places it in the range of a small feeder ship.[11][15] The ship's gross tonnage, a measure of the volume of all its enclosed spaces, is 4,276.[1][16] Its net tonnage, which measures the volume of the cargo spaces, is 2,129.[1][16] Its total carrying capacity in terms of weight, is 5,055 long tons deadweight (DWT), the equivalent of almost 170 Sherman tanks.[1]

Steamer's Future was built with a Wärtsilä Vasa 9R32E main engine which drives a controllable-pitch propeller.[9] This is a four-stroke diesel engine, that is turbocharged and intercooled.[17] This engine also features direct fuel injection.[17] It has nine in-line cylinders, each with a 320 mm cylinder bore, and a 350 mm stroke.[17] At 720 revolutions per minute (RPM), the engine produces a maximum continuous output of 3,645 kilowatts (4,888 hp), and at 750 RPM 3,690 kilowatts (4,950 hp).[17] According to Military Sealift Command, the ship's cruising speed is 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph).[10]

In addition, the ship has a Schottel SST170LKT maneuvering thruster.[9]

The ship was built with two 400-kilowatt (540 hp) Wärtsilä UD 25 L6 55D auxiliary generators, backed-up by a Cummins emergency diesel generator.[9] At some point prior to 21 April 2011, the #2 ship's service diesel generator was replaced with a Caterpillar C-18 diesel generator. This unit runs between 1,500 and 1,800 RPM and supplies between 301-602 kilowatts of electrical power. It burns between 16.6 to 38.3 US gallons (63 to 145 l; 13.8 to 31.9 imp gal) per hour of diesel fuel and weighs between 3,900 pounds (1,800 kg) and 4,200 pounds (1,900 kg). This generator has a 145-millimetre (5.7 in) bore and a 183-millimetre (7.2 in) stroke.[18]

TransAtlantic has two Liebherr rotary cargo cranes. Ships with cranes, known as geared ships, are more flexible in that they can visit ports that are not equipped with pierside cranes.[19] However, having cranes on board also has drawbacks.[19] This added flexibility incurs some costs greater recurring expenses, such as maintenance and fuel costs.[19] The United Nations Council on Trade and Development characterizes geared ships as a "niche market only appropriate for those ports where low cargo volumes do not justify investment in port cranes or where the public sector does not have the financial resources for such investment."[19] Slightly less than a third of the ships in TransAtlantic's size range (from 100–499 TEU) are geared.[19]

Construction of the ship was completed in 1997.[1] As of 2011, the ship is classified by Det Norske Veritas with the code "![]()

History

Under the Singaporean flag

In 1983, Singapore's Keppel Corporation acquired one of Singapore's oldest shipping concerns, the Straits Steamship Company, founded in 1890.[21] After the acquisition, Keppel renamed the company Steamers Maritime Holdings Company.[21][22] The company laid the keel for Steamer's Future on 8 February 1996, but as early as 1997, the Keppel conglomerate began to exit the shipping industry.[22] Shortly thereafter, Steamers was renamed Keppel Telecommunications & Transportation,[22] and in March 2004, Keppel announced the sale of "the entire Steamers fleet of 10 ships to Interorient for $90.9m in order to concentrate on core activities."[23]

Interorient kept seven of these ships for its Mediterranean-based United Feeder Services operation, but sold Steamers Future and two other ships to Hamburg-based shipowner Rehder & Arkon, a division of the Carsten Rehder company.[23] In April 2004, Rehder & Arkon renamed the ship Baffin Strait, and chartered her for six months to Mariana Express Lines.[11] In late October 2004, Rehder & Arkon sold the ship to the U.S. company TransAtlantic Lines for US$6.3 million.[11][24][25]

Under the United States flag

As of 2011, the ship is owned and operated by TransAtlantic Lines, an American shipping company based in Greenwich, Connecticut.[26] This limited liability company was founded in 1998 by vice-president Gudmundur Kjaernested and president Brandon C. Rose.[26][27] The company owns and operates five vessels, including one tug-and-barge combination. Four of these vessels are currently or have been chartered by the Military Sealift Command, and perform duties such as delivering cargo to the U.S. military base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba and oil products to bases in the Western Pacific. TransAtlantic Lines has no collective bargaining agreements with seagoing unions.[28]

Diego Garcia charter

In 2004, TransAtlantic Lines outbid Sealift Incorporated for the contract to haul cargo between Singapore and Diego Garcia.[28] The route had previously been serviced by Sealift's MV Sagamore which was manned by members of American Maritime Officers and Seafarer's International Union.[28] TransAtlantic Lines reportedly won the contract by approximately 10 percent, representing a price difference of about $2.7 million.[28]

As a result of winning this contract, the US Navy gave the Baffin Strait the hull classification symbol T-AK W9519. The T-AK series symbol is given to the seven container ships chartered by MSC but owned and operated by contractors.[7]

The Baffin Strait's Diego Garcia charter ran from 10 January 2005 to 30 September 2008 on a daily rate of $12,550 under contract number N00033-05-C-5500.[29] Nicknamed "the DGAR shuttle", the ship delivered 250 containers each month from Singapore to Diego Garcia, carrying everything from fresh food to building supplies to aircraft parts, and delivering more than 200,000 tons of cargo to the island each year."[12] When returning from Diego Garcia, the ship carried metal waste to be recycled in Singapore.[30]

The Sealift Program Office's mission is to provide high-quality, efficient and cost-effective ocean transportation for the Department of Defense and other U.S. government agencies.[31] The program is divided into three project offices: Tankers, Dry Cargo, and Surge.[31] Dry cargo is shipped by U.S.-flagged commercial ships.[31] Approximately 80 percent of this cargo is transported aboard regularly scheduled U.S. commercial ocean liners.[31] The other 20 percent is carried by four cargo ships under charter to MSC.[31]

On the evening of 22 April 2009, Baffin Strait was involved with a collision with the car carrier Jasmine Ace while both vessels were anchored in Singapore.[32] A severe squall moved into the area while Jasmine Ace was taking fuel.[32] The squall caused the ship to drag its anchor.[32] The car carrier drifted downwind, causing its starboard quarter to strike Baffin Strait's starboard side.[32] As a result, Baffin Strait's anchor also began to drag, and the crew dropped a second anchor to hold the ship.[32] The two ships were "married for several minutes", during which time the Jasmine Ace started her engine.[32] The Baffin Strait's damage included "disfigured" steel on the starboard bulwark and damage to the starboard running light.[32]

On 27 March 2009, Military Sealift Command announced a request for proposals (number N00033-09-R-5502) for the Diego Garcia service.[33] The charter contract would be for a one-year probation period, followed by three one-year options, and concluding with an eleven-month option.[33] The fixed-price time charter would be supplemented by reimbursements for costs such as the ship's fuel.[33] The RFP stipulated that the charter would be awarded to the lowest-priced proposal which the Navy found technically acceptable.[34]

Six companies submitted proposals, with TransAtlantic proposing the MV Rio Bogota (which it intended to rename Heidi B) to replace the Baffin Strait.[34] While the Navy was assessing the proposals, rival shipping company Sealift Incorporated secured the rights to operate Rio Bogota, and TransAtlantic countered by altering its proposal to offer the ship MV LS Aizenshtat instead.[34][35] The Navy deemed both companies' proposals technically acceptable and their past performance satisfactory.[35] Sealift's proposed rate, was more than $3 million less than TransAtlantic's ($39,031,093 versus $42,415,356), and they were awarded the charter.[35] After winning the contract, Sealift purchased Rio Bogota on 21 August 2009.[35]

2010–2011 shipyard period

After finishing the Diego Garcia contract, the ship sailed from Singapore on 19 November 2009 for a shipyard period in Wilmington, North Carolina by way of the Suez Canal.

On 16 January 2010, while pierside in Wilmington, the ship was picketed by members of the Seafarers International Union.[36] According to the union's Assistant Vice President, Bryan Powell, crewmembers' "wages are substandard. They don't get any overtime. They are basically on salary, so they can work them 16 hours a day and get the same low rates of pay, which we think is ridiculous".[36] The union claimed that the picket was in support of crewmembers, encouraging them to unionize the ship, and take their case to the Department of Labor.[36]

On 31 March 2010, industry journal Tradewinds reported that Baffin Strait was the first vessel ever to be involuntarily disenrolled from the United States Coast Guard's Alternative Compliance Program, in which the Coast Guard delegates inspections and certificate issuance to the vessel's classification society.[37] The move was prompted by deficiencies to the ship's firefighting and lifesaving programs reported by Coast Guard inspectors in Singapore remaining unresolved. According to the Coast Guard's program manager for domestic vessel inspections, inspectors "didn't see a pattern of improvement over time".[37]

In May 2010, the ship was towed to Ciramar Shipyard in the Dominican Republic for more extensive repairs.

Notes

- Det Norske Veritas, Summary, 2007.

- United States Coast Guard PSIX, 2008.

- Det Norske Veritas, Previous Flags, 2007.

- Det Norske Veritas, Previous Names, 2007.

- Det Norske Veritas, Yard Information, 2007.

- Det Norske Veritas, Class, 2007.

- "MV Baffin Strait". Military Sealift Command Ship Inventory. Military Sealift Command. 24 October 2006. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- Det Norske Veritas, Dimensions, 2007.

- Det Norske Veritas, Machinery, 2007.

- MSC Baffin Strait Page

- Fearnresearch (2005). "Fearnley's Annual Review, 2004" (PDF). Oslo: Fearnleys AS. p. 90. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- MSC Public Affairs (8 November 2007), Change at the helm for MSC's Diego Garcia office, Singapore: Sealift Logistics Command Far East, archived from the original (Press Release) on 6 August 2011, retrieved 3 August 2011

- Det Norske Veritas, Hull, 2007.

- "International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969". International Conventions. Admiralty and Maritime Law Guide. 23 June 1969. Retrieved 27 October 2007.

- MAN Diesel, 2009, p.6.

- International Maritime Organization, 2002.

- http://www.brownsequipment.com/files/item_files/files/12338.pdf

- http://marine.cat.com/cat-C18-auxiliary

- UNCTAD, 2010, p. 32.

- The code is given at the DNV Exchange, and explained on Det Norske Veritas, January 2011, pp. 5, 18.

- Keppel T&T Report to Shareholders, 2003. p.43

- Keppel Corporation Ltd.

- Trade Winds (5 March 2004). "Interorient Navigation keeps seven Keppel feeders". carstenrehder.de. Trade Winds. Archived from the original on 14 January 2005. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- Rehder & Arkon (October 2004). "Rehder & Arkon sold MV BAFFIN STRAIT". www.rehder-arkon.de. Rehder & Arkon. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- "October 2004 Sales". shiplink.info. Archived from the original on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- Dun and Bradstreet, 2007.

- United States Court of Appeals, 2000.

- American Maritime Officers (November 2004). "Non-union operator wins charter held by Sagamore". AMO Currents. Archived from the original on 20 July 2006. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- MSC Procurement Spreadsheet

- Commander, Navy Installations Command (CNIC) (2007). "2006 Pollution Provention and Solid Waste Success Stories" (PDF). U.S. Department of the Navy. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- Military Sealift Command. "Ship Inventory: Sealift Ships". msc.navy.mil. United States Navy. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- Investigation Activity Report: JASMINE ACE; Collision On: 4/22/2009

- Gibson, 2009, p. 1.

- Gibson, 2009, p. 2.

- Gibson, 2009, p. 3.

- Hosmann, Claire (16 January 2010). "Union holds informational picket for better wages and benefits". Wilmington, North Carolina: WECT Channel 6. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- Stamford, Bob Rust (31 March 2010). "Vessel ejected from US scheme" [A history of deficiencies has led US officials to kick out a US-flag vessel.]. Oslo, Norway: Tradewinds AS. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

References

- "Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia" (PDF). 11 January 2000. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- Det Norske Veritas (January 2011). "Part 1, Chapter 2: Class Notations". Rules for the Classification of Ships (PDF). Høvik, Norway: Det Norske Veritas AS. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- Gibson, Lynn H. (24 November 2009). "Decision, Matter of TransAtlantic Lines, LLC, File B-401825" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Accountability Office. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- International Maritime Organization (2002). "International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships, 1969". International Maritime Organization. Archived from the original on 16 January 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- "TransAtlantic (9148520)". Equasis. French Ministry for Transport. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- "LS Aizenshtat (9117753)". Equasis. French Ministry for Transport. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Mohegan (9100243)". Equasis. French Ministry for Transport. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- "Baffin Strait (25708)". DNV GL Vessel Register. Det Norske Veritas.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2010). Review of Maritime Transport, 2010 (PDF). New York and Geneva: United Nations. ISBN 978-92-1-112810-9.

- "Baffin Strait (708628)". Port State Information Exchange. United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

External links

| External images | |

|---|---|

In 2001, the ship was named MV Steamers Future. | |

MV Baffin Strait approaching the Bani Terminal in Singapore in December 2007. | |

Baffin Strait near the time she was purchased by TransAtlantic Lines in October 2004. | |

- Military Surface Deployment and Distribution Command 2007 Charter Cargo Billing Rates

- Contract N0003305C5500 at USAspending.gov

- Diego Garcia contract awarded to Sealift Inc.

- Record of both 2004 sales at Tradewinds

- May-July 2011 MSC Time Charter

- Vessel stranded in Kiel due to serious engine trouble

- Loss of statutory certificate sees TAL fleet sidelined by US for military contracts

- Previous owners