Harad

In J. R. R. Tolkien's heroic romance The Lord of the Rings, Harad is the immense land south of Gondor and Mordor. Its main port is Umbar, the base of the Corsairs of Umbar whose ships serve as the Dark Lord Sauron's fleet. Its people are the dark-skinned Haradrim or Southrons; their warriors wear scarlet and gold, and are armed with swords and round shields; some ride gigantic elephants called mûmakil.

| Harad | |

|---|---|

| J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium location | |

| |

| First appearance | The Fellowship of the Ring |

| Information | |

| Type | Vast hot southern region |

| Notable locations | Umbar, Near Harad, Far Harad |

| Other name(s) | Haradwaith, Hyarmen, the Sunlands |

Tolkien based the Haradrim on ancient Aethiopians, people of Sub-Saharan Africa, following his philological research on the Old English word Sigelwara. He deduced that this word referred to some kind of soot-black fire demon before it was applied to the Aethiopians. He based the Haradrim's use of war elephants, meanwhile, on that of Pyrrhus of Epirus in his war against Ancient Rome. Critics have debated whether Tolkien was racist in making the protagonists white and the antagonists black, but others have noted that he was strongly anti-racist in real life, opposing any attempt to demonise the enemy in both World Wars.

In Peter Jackson's film The Two Towers, the Haradrim were based on 12th century Saracens; they have turbans and flowing robes, and they ride elephants. The Haradrim appear in a variety of games and merchandise inspired by The Lord of the Rings.

Middle-earth narrative

Geography

Harad is a large land in the south of Middle-earth, bordered to the north by (from west to east) the lands of Gondor, Mordor, Khand and Rhûn. Historically the border with Gondor was to be the river Harnen, but by the time of the War of the Ring all the land further north to the river Poros is under the influence of the Haradrim. The border with Mordor runs along the southern Mountains of Shadow. Harad's west coast (the nearest to Gondor) is washed by the Great Sea, the western ocean of Middle-earth. Harad's eastern shores looks out on the Eastern Sea, Middle-earth's eastern ocean.[T 1]

The elves named the land and its people Haradwaith, "South-folk", from the Sindarin harad, meaning "south", and gwaith, meaning "people".[2] The Quenya word Hyarmen similarly means "south" in addition to being the name of the country. The hobbits called the area the Sunlands, and the people Swertings.[T 2] Aragorn briefly describes his journeys in the land as being in "Harad where the stars are strange".[T 3] Tolkien confirmed that this meant that Aragorn had traveled "some distance into the southern hemisphere" in Harad.[T 4]

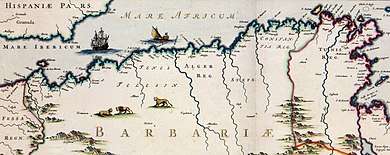

The great harbour city of Umbar lies on Harad's north-west coast; its natural harbour is the base of the Corsairs of Umbar, inspired by the Barbary pirates,[1] who provide the Dark Lord Sauron with a sizeable fleet. The ships are different types of galleys, with both oars and sails; some are named as dromunds, others as having a deep draught (requiring a deep channel), many oars, and black sails.[3][4][5][T 5]

Elsewhere in Harad there are "many towns";[T 6] one of these is "the inland city", the home of Queen Berúthiel (mentioned by Tolkien in an interview).[6] The Harad Road is the main overland route between Gondor and Harad.[T 7] Harad possesses jungles with apes,[T 8] grasslands,[T 9] mountains and deserts. There are large elephants known as mûmakil, influenced by the zoologist Georges Cuvier's 1796 discovery of bones and palaeolithic drawings of mammoths.[7]

Gondor described Harad as consisting of Near Harad and Far Harad. Near Harad corresponds loosely with North Africa or the Maghreb, while Far Harad, the vastly larger of the two regions, corresponds loosely with sub-Saharan Africa. Tolkien's own annotated map of Middle-earth, used by the illustrator Pauline Baynes to construct her iconic map, suggests that "Elephants appear in the great battle outside Minas Tirith (as they did in Italy under Pyrrhus) but they would be in place in the blank squares of Harad – also camels."[8]

People

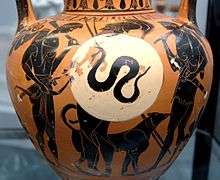

The Men of Harad are called Haradrim ("South-multitude"), Haradwaith, or Southrons by the people of Gondor. The Haradrim are of various ethnicities and cultures; some are organized into kingdoms.[T 10][T 11] Frodo and Sam meet Faramir and his Rangers of Ithilien just before the latter ambush a company of Haradrim on the North Road. Frodo and Sam do not see much of the battle, since they are positioned elsewhere, but they hear the sounds of fighting, and a slain Haradrim warrior crashes at their feet. This warrior is described as having "brown" skin, with black plaits of hair braided with gold.[T 10] He wears a scarlet tunic, as do the other Haradrim, and a gold collar. He is armed with a sword and has a corslet of brazen scales. Their standards are scarlet, and their great beasts, the mûmakil, have scarlet and gold trappings. They carry round spiked shields, painted yellow and black. Their leaders have a serpent emblem.[T 10] The people of Far Harad were black-skinned; a group of them is described as "black men like half-trolls with white eyes and red tongues" and "troll-men".[T 12]

History

The Haradrim are independent peoples, but in the Second Age they are caught between the ambitions of Sauron (the Dark Lord) and the Númenóreans, who often kill Haradrim or sell them as slaves, and who become rulers of Harad. Over the centuries many Haradrim fall under Sauron's dominion, and to "them Sauron was both king and god, and they feared him exceedingly".[T 13] They become mixed with Númenórean settlers, some of whom fall under the sway of Sauron as "Black Númenóreans".[T 14][10] Under King Hyarmendacil I "South-victor" of Gondor, Harad becomes a vassal of Gondor.[T 15] By the time of the War of the Ring, the Haradrim are again under the dominion of Sauron, and the Haradrim Corsairs provide the whole of his Black Fleet; many other Haradrim join his armies, some riding mûmakil. In the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, the leader of the Haradrim army is killed by King Théoden of Rohan.[T 16][T 17]

Tolkien did not work out any particular languages for the Haradrim, though mûmak, "elephant", may be in the Harad language.[11] Despite having a meaning in Quenya ("fate"), the name Umbar is adapted from the natives' language and not from Elvish or Adûnaic.[12]

Concept and creation

"Sigelwara Land"

Tolkien arrived at the idea of Harad, a hot Southern land, through his philological work. The Old English Biblical poem Exodus in the tenth-century Codex Junius 11 includes a passage that caught Tolkien's attention:[13]

| Codex Junius 11 (Old English) | Modern English[14] |

|---|---|

| .. be suðan Sigelwara land, forbærned burhhleoðu, brune leode, hatum heofoncolum. | "... southward lay the Ethiop's land, parched hill-slopes and a race burned brown by the heat of the sun." |

Tolkien was interested in particular in the Old English word used for "Aethiopians": it was Sigelwara, or in Tolkien's emendation Sigelhearwan.[16] The critic Tom Shippey writes that Tolkien's philological research, described in his essay "Sigelwara Land",[T 18] began from the assumption that the word could not originally have meant Aethiopian, but must have been co-opted to that usage having once meant something comparable. Tolkien approached the question by analysing the two parts of the word. Sigel meant, according to Tolkien, "both sun and jewel", the former as it was the name of the Sun rune *sowilō (ᛋ), the latter connotation from Latin sigillum, a seal.[15]

Tolkien decided that Hearwa was related to the Old English heorð, meaning "hearth", and ultimately to the Latin carbo, meaning "soot". The resulting meaning for Sigelhearwan, Tolkien decided tentatively, was "rather the sons of Muspell than of Ham", an ancient class of demons in Northern mythology "with red-hot eyes that emitted sparks and faces black as soot".[T 18][lower-alpha 1] This was exactly the sort of "stray pagan concept"[18] hinting at England's lost mythology that Tolkien wanted.[18]

In drafts of The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien toyed with names such as Harwan and Sunharrowland for Harad, which were derived from Sigelwara; Christopher Tolkien notes that these are connected to his father's Sigelwara Land.[9] The philologist Elizabeth Solopova similarly notes that the hobbits' name for Harad, Sunland, suggests a link to Sigelwara Land.[19]

Moral geography

The Germanic studies scholar Sandra Ballif Straubhaar notes that it is not clear whether Tolkien meant the Haradrim to be grouped with his "Wild Men", though he named them as ancient enemies of Gondor. They are "ethnic others but not as ugly",[10] they have a rich culture and well-trained elephants. The exception would be, she suggests, the men of Far [Southern] Harad whom the people of Gondor saw as "black men like half-trolls with white eyes and red tongues".[10][21] With his "Southrons" from Harad, Tolkien had – in the view of John Magoun, writing in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia – constructed a "fully expressed moral geography",[20] from the hobbits' home in the Northwest, evil in the East, and "imperial sophistication and decadence" in the South. Magoun explains that Gondor is both virtuous, being West, and has problems, being South; Mordor in the Southeast is hellish, while Harad in the extreme South "regresses into hot savagery".[20][lower-alpha 2]

Solopova argues that the Haradrim's mûmakil war elephants put their country far to the East, since only India and lands to its east went on using war elephants after classical times.[19] Lee and Solopova also mention that Tolkien could have used the Old English version by Ælfric of the Book of Maccabees, which carefully introduces elephants to its Anglo-Saxon audience, using much the same phrase as Sam Gamgee, "māre þonne sum hūs", "bigger than a house", before describing their use in battle; the hero stabs the elephant, which is carrying a "wīghūs", a "battle-house", from below.[24] David Day suggests that Tolkien could have been inspired to provide the Haradrim with mûmakil for the Battle of the Pelennor Fields by Hannibal's use of elephants in the 202 BC Battle of Zama, in what is now Tunisia.[7] Tolkien however mentioned Pyrrhus of Epirus's use of war elephants against Ancient Rome in 280–275 BC in his notes for the illustrator Pauline Baynes.[8]

The stereotypical "Other"

Tolkien has frequently been accused of racism, but the Indigenous studies scholar Lisa Tatonetti writes that even though "his textual imagery often aligns with racialized ideologies", Tolkien was sharply anti-racist in the Second World War.[25][26] Straubhaar writes that "a polycultured, polylingual world is absolutely central"[27] to Middle-earth, and that readers and filmgoers will easily see that. From there, she notes that the "recurring accusations in the popular media" of a racist view of the story are "interesting". She quotes the Swedish cultural studies scholar David Tjeder who described Gollum's account of the men of Harad ("Not nice; very cruel wicked Men they look. Almost as bad as Orcs, and much bigger."[T 19]) in Aftonbladet as "stereotypical and reflective of colonial attitudes".[28] She argues instead that Gollum's view, with its "arbitrary and stereotypical assumptions about the 'Other'",[28] is absurd, and that Gollum cannot be taken as an authority on Tolkien's opinion. Straubhaar contrasts this with Sam Gamgee's more humane response to the sight of a dead Harad warrior, which she finds "harder to find fault with": "He was glad that he could not see the dead face. He wondered what the man's name was and where he came from; and if he was really evil of heart, or what lies or threats had led him on the long march from his home."[T 20][28] Straubhaar quotes the English scholar Stephen Shapiro, who wrote in The Scotsman that "Put simply, Tolkien's good guys are white and the bad guys are black, slant-eyed, unattractive, inarticulate, and a psychologically undeveloped horde".[29][30] Straubhaar concedes that Shapiro may have had a point with "slant-eyed", but comments that this was milder than that of many of his contemporary novelists such as John Buchan, and notes that Tolkien had in fact made "appalled objection" when people had misapplied his story to current events.[29] She similarly observes that Tjeder had failed to notice Tolkien's "concerted effort" to change the Western European "paradigm" that speakers of supposedly superior languages were "ethnically superior".[31]

In other media

In Peter Jackson's film The Two Towers, the Haradrim appear Middle Eastern, with turbans, flowing robes, and riding elephants. A companion book on the film's "Creatures" states that the Haradrim were based on 12th century Saracens.[32]

The Haradrim and the Corsairs of Umbar appear in much merchandise for the film trilogy, such as toys, The Lord of the Rings Trading Card Game, and the computer game The Lord of the Rings: The Battle for Middle-earth II.[33][34][35] "Haradrim Slayers" feature in the computer game The Lord of the Rings: War of the Ring,[36] while in the video game Middle-earth: Shadow of War, Baranor, a playable character who is a captain in Gondor's guard, is originally from Harad.[37]

Iron Crown Enterprises produced a series of books for their tabletop roleplaying game Middle-earth Role Playing containing information about Harad and content allowing games to be set there. Key publications included the setting books Umbar: Haven of the Corsairs (1982),[38] Far Harad (1988),[39] and Greater Harad (1990),[40] as well as the adventure books Warlords of the Desert (1989),[41] Forest of Tears (1989),[42] and Hazards of the Harad Wood (1990).[43] Games Workshop have produced miniatures and rules relating to Harad for use in the Middle Earth Strategy Battle Game, including for mumakil and Corsairs of Umbar.[44][45]

See also

- Calormenes, a race of men from a hot southern land from CS Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia[46]

Notes

- Shippey states that this analysis of Sigelhearwa both "helped to naturalise the Balrog" (a demon of fire) and contributed to the Silmarils, which combined the nature of the sun and jewels.[17]

- Other scholars such as Walter Scheps and Isabel G. MacCaffrey have noted Middle-earth's "spatial cum moral dimensions"..[22][23]

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1977), The Silmarillion, George Allen & Unwin, 'Akallabêth' p. 263; ISBN 0 04 823139 8

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1954), The Two Towers, 2nd edition (1966), George Allen & Unwin, book 4 ch 3, "The Black Gate is Closed", ISBN 0 04 823046 4 "I've heard tales of the big folk down away in the Sunlands. Swertings we call 'em in our tales; and they ride on oliphaunts, 'tis said, when they fight."

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Fellowship of the Ring, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), "The Council of Elrond", ISBN 0-395-08254-4

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1980), Unfinished Tales, George Allen & Unwin, part 4 ch. III 'The Istari' p. 402 note 10; ISBN 0-04-823179-7

- The Battle of the Pelennor Fields. The Return of the King.

for black against the glittering stream they beheld a fleet borne up on the wind: dromunds, and ships of great draught [with deep hulls] with many oars, and with black sails bellying in the breeze.

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1977), The Silmarillion, George Allen & Unwin, 'Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age', p. 290; ISBN 0 04 823139 8

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1955), The Return of the King, 2nd edition (1966), George Allen & Unwin, book 6 ch. 2 p. 201; ISBN 0 04 823047 2

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1954), The Two Towers, George Allen & Unwin 2nd ed.1966, bk 3 ch VII p 140 ("apes in the dark forests of the South"), ISBN 0 04 823046 4

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1955), The Return of the King, George Allen & Unwin 2nd ed.1966, Appendix A:II p 352 ("the far fields of the South"), ISBN 0 04 823047 2

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1954), The Two Towers, 2nd edition (1966), George Allen & Unwin, book 4 ch 4, "Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit", ISBN 0 04 823046 4

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1955), The Return of the King, 2nd edition (1966), George Allen & Unwin, Appendix A §I(iv) ISBN 0 04 823047 2

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1954), The Return of the King, 2nd edition (1966), George Allen & Unwin, book 5 ch 6, "Battle of the Pelennor Fields", ISBN 0 04 823047 2

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1977), The Silmarillion, George Allen & Unwin, 'Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age', p. 289-290; ISBN 0 04 823139 8

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1955), The Return of the King, 2nd edition (1966), George Allen & Unwin, Appendix A §I(iv) p. 325 footnote; ISBN 0 04 823047 2

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1955), The Return of the King, 2nd edition (1966), George Allen & Unwin, Appendix A §I(iv) p. 325; ISBN 0 04 823047 2

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1955), The Return of the King, 2nd edition (1966), George Allen & Unwin, book 5 ch. VI p. 124 & book 6 ch. IV p. 227; ISBN 0 04 823047 2

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1955), The Return of the King, 2nd edition (1966), George Allen & Unwin, book 6 ch. 5 p. 246-247; ISBN 0 04 823047 2

- J. R. R. Tolkien, "Sigelwara Land" Medium Aevum Vol. 1, No. 3. December 1932 and Medium Aevum Vol. 3, No. 2. June 1934.

- Lord of the Rings, book 4, ch. 3 "The Black Gate is Closed"

- Lord of the Rings, book 4, ch. 4 "Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit"

Secondary

- Bowers, John M. (2019). Tolkien's Lost Chaucer. Oxford University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-19-258029-0.

- Tyler, J. E. A. (2002). The Complete Tolkien Companion. Pan Books. pp. 307–308. ISBN 978-0-330-41165-3.

- Morwinsky, Thomas (January 2008). "Númenórean Maritime Technology". Other Minds Magazine (2): 28–29.

- Day, David (2015). A Dictionary of Tolkien: A-Z. Octopus. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-7537-2855-0.

- Cole, Michael (March 2015). "Pirates of Middle Earth" (PDF). RPG Review (26–27): 56–73.

- "The Realms of Tolkien". originally published in New Worlds in November 1966, reprinted in Carandaith in 1969 and again in Fantastic Metropolis in 2001. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Day, David (2019). A Dictionary of Sources of Tolkien. Octopus. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-7537-3406-3.

- Kennedy, Maev (3 May 2016). "Tolkien annotated map of Middle-earth acquired by Bodleian library". The Guardian.

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1989), ed. Christopher Tolkien, The Treason of Isengard, Unwin Hyman, ch. XXV p. 435 & p. 439 note 4 (comments by Christopher Tolkien)

- Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2006). "Men, Middle-Earth". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 415–417. ISBN 1-135-88034-4.

- Tyler, J. E. A. (2002). The Complete Tolkien Companion. Pan Books. p. 446. ISBN 978-0-330-41165-3.

- Flieger, Verlyn (2009). "The Music and the Task: Fate and Free Will in Middle-earth". Tolkien Studies. 6: 157. doi:10.1353/tks.0.0051.

...in primitive Quenya umbar, 'fate,' ...

- Shippey 2005, p. 54.

- "Junius 11 "Exodus" ll. 68-88". The Medieval & Classical Literature Library. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Shippey 2005, pp. 48-49.

- Shippey 2005, p. 48.

- Shippey 2005, p. 49.

- Shippey 2005, pp. 54, 63.

- Lee, Stuart; Solopova, Elizabeth (2016). The Keys of Middle-earth: Discovering Medieval Literature Through the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-137-45470-6.

- Magoun, John F. G. (2006). "South, The". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 622–623. ISBN 1-135-88034-4.

- Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2006). "Saracens and Moors". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 588–589. ISBN 1-135-88034-4.

- Scheps, Walter (1975). Lobdell, Jared (ed.). The Interlace Structure of 'The Lord of the Rings'. A Tolkien Compass. Open Court. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0875483030.

- MacCaffrey, Isabel G. (1959). Paradise Lost as Myth. Harvard University Press. p. 55. OCLC 1041902253.

- Lee, Stuart D.; Solopova, Elizabeth (2005). The Keys of Middle-earth: Discovering Medieval Literature Through the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien. Palgrave. pp. 223-225, 228–231. ISBN 978-1403946713. translating the Homily on the Maccabees. II, 499-519.

- Tatonetti, Lisa (2011). "Indingenous fantasies and sovereign erotics: Outland Cherokees write two-spirit nations". In Driskill, Qwo-Li (ed.). Queer Indigenous Studies: Critical Interventions in Theory, Politics, and Literature. University of Arizona Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8165-2907-0.

- Rearick, Anderson (2004). "Why is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc? The Dark Face of Racism Examined in Tolkien's World". Modern Fiction Studies. 50 (4): 866–867.

- Straubhaar 2004, p. 112.

- Straubhaar 2004, p. 113.

- Straubhaar 2004, p. 114.

- Shapiro, Stephen (14 December 2002). "Lord of the Rings labelled racist". The Scotsman.

- Straubhaar 2004, p. 115.

- Ibata, David (12 January 2003). "'Lord' of racism? Critics view trilogy as discriminatory". Chicago Tribune.

The Haradrim are more recognizable. They are garbed in turbans and flowing crimson robes. They ride giant elephants. They resemble nothing other than North African or Middle Eastern tribesmen. A recently released "Towers" companion book, "The Lord of the Rings: Creatures," calls the Haradrim "exotic outlanders" whose costumes "were inspired by the twelfth-century Saracen warriors of the Middle East."

- Radcliffe, Doug. "The Lord of the Rings, The Battle for Middle-earth II Game Guide. Walkthrough: Evil Campaign". Gamespot. CBS Interactive.

- Kerkhove, Devon (21 September 2005). "The Lord of the Rings: Online Trading Card Game – Starter Deck Guide". GameFAQs.

- Rorie, Matthew (17 July 2006). "The Lord of the Rings, The Battle for Middle-earth II Walkthrough". Gamespot.

- "The Lord of the Rings: War of the Ring - Perfect Walkthrough". IGN. 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Carter, Chris (8 May 2015). "Review: Middle-earth: Shadow of War - Desolation of Mordor". Destructoid. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- Spielman, Brenda Gates (1982). Umbar: Haven of the Corsairs. Iron Crown Enterprises.

- Crutchfield, Charles (1988). Far Harad. Iron Crown Enterprises.

- Wilson, WIlliam E. (1990). Greater Harad. Iron Crown Enterprises.

- Crutchfield, Charles (1989). Warlords of the Desert. Iron Crown Enterprises.

- Crutchfield, Charles (1989). Forest of Tears. Iron Crown Enterprises.

- Crowdis, John (1990). Hazards of the Harad Wood. Iron Crown Enterprises.

- "War Mûmak Of Harad". Games Workshop. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "Corsairs of Umbar". Games Workshop. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Ford, Paul F. (2005) [1980]. Companion to Narnia: A Complete Guide to the Enchanting World of C.S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia (5th ed.). HarperCollins. p. 127. ISBN 0-06-079127-6.

Sources

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). Grafton (HarperCollins). ISBN 978-0261102750.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2004). Chance, Jane (ed.). Myth, Late Roman History, and Multiculturalism in Tolkien's Middle-Earth. Tolkien and the invention of myth : a reader. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 101–117. ISBN 978-0-8131-2301-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

.jpg)