Louis T. Wright

Louis Tompkins Wright, MD, FACS[1] (July 23, 1891 – October 8, 1952)[2] was an American surgeon and civil rights activist. In his position at Harlem Hospital he was the first African-American on the surgical staff of a non-segregated hospital in New York City. He was influential for his medical research as well as his efforts pushing for racial equality in medicine and involvement with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which he served as chairman for nearly two decades.[3][4]

Louis Wright | |

|---|---|

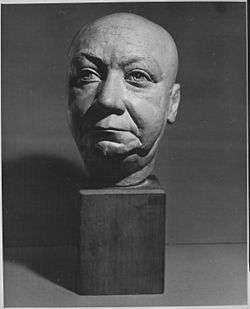

Louis T. Wright (sculpture by William E. Artis) | |

| Born | July 23, 1891 |

| Died | October 8, 1952 (aged 61) New York City, New York |

| Nationality | United States |

| Alma mater | Harvard Medical School Clark Atlanta University |

| Known for | First African-American surgeon at Harlem Hospital; Chairman of the NAACP |

| Awards | Spingarn Medal Purple Heart |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine |

| Institutions | Harlem Hospital, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People |

Early life and family

Wright was born in LaGrange, Georgia. His father, Ceah Ketchan Wright, was born a slave but obtained formal education, finishing medical school as valedictorian but later giving up his medical practice to be a Methodist minister.[5] Ceah died shortly after Louis's birth and his mother, a sewing teacher named Lula Tompkins, remarried in 1899. Also a physician, Louis's step-father, William Fletcher Penn, was the first African-American to graduate from Yale School of Medicine.[6] Penn, who became a prominent doctor in Atlanta and was the first African-American to own an automobile in the city, had a strong influence on Louis both as a physician and through the racism Louis watched him endure.[5]

Wright graduated from Clark Atlanta University in 1911 and received his medical degree from Harvard Medical School in 1915, finishing fourth in his class.[2] Dr. Wright's admission to Harvard Medical School must be recognized as no easy feat. Despite being a very educated individual, Wright was deemed unfit by Channing Frothingham, MD––one of the medical school's interviewers––due to his attendance of an undergraduate institution that permitted blacks. However, after subjecting Wright to numerous tests, Dr. Frothingham ultimately ruled that he had "adequate chemistry for admission to this school."[7] He completed his postgraduate work at Howard University-affiliated Freedmen's Hospital in Washington, DC before returning to Georgia.[4]

He married public school teacher Corinne Cooke, and the couple had two daughters, Jane Cooke Wright and Barbara Wright Pierce, both of whom also became physicians and researchers.[6]

Medical career

Shortly after completing medical school and moving back to Georgia, Wright joined the Army Medical Corps, serving as a lieutenant during World War I, stationed in France. While there he introduced intradermal vaccination for smallpox and was awarded the Purple Heart after a gas attack.[2][4]

Upon returning to the United States in 1919, he moved to New York amid racial tensions in Georgia to set up a private practice in Harlem and established ties to the Harlem Hospital, where he was the first African-American on the surgical staff.[2] Dr. Wright's implementations at Harlem Hospital were incredibly significant. He addressed the institution's issues of professionalism and quality of standards, and made the appropriate changes. Wright's additions gained the attention of the nation, and his revisions were eventually implemented into many hospitals nationwide.[8] In 1929 he was also appointed to serve as the first African-American police surgeon with the New York Police Department.[2][9] In his thirty years at the hospital he started the Harlem Hospital Bulletin, headed the team that first used chlortetracycline on humans, founded the hospital's cancer research center, and earned a reputation as an expert on head injuries.[10] He was a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons[11] and the American Medical Association.[9]

Civil rights activism and leadership

Throughout his life Wright involved himself in civil rights efforts, beginning in college when he missed three weeks of school to join picket lines protesting D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation, a film controversial for its sympathetic portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan.[9] At Harvard he insisted on equal treatment when a professor prevented him from delivering white patients' babies.[2] He joined the NAACP after medical school and remained involved with the organization for the rest of his life, eventually serving as chairman of its national board of directors.

Dr. Wright's work at the NAACP did not go unnoticed. For the better part of a decade, he wrote multiple columns in The Crisis, the NAACP's magazine publication.[8] The majority of Wright's work dealt with issues that are still brought up by modern black authors, such as Harriet A. Washington. Dr. Wright challenged the false beliefs that because of their biology, black people are more susceptible to infectious diseases—such as syphilis—than other races.[8]

He was a frequent leader in the struggle for integration, especially in medicine. In 1920, early in his tenure at Harlem Hospital, he played a key role in fighting the precedent in New York whereby African-American doctors and nurses were barred from serving in municipal hospitals. He actively opposed segregated hospitals, including a successful effort in 1930 to stop the construction of a new such facility proposed by the Rosenwald Fund.[4][5] In working towards equality in medicine and medical education, he advocated for raising standards for black medical students, leading to some pushback from peers whom had become used to having a different set of requirements.[12]

In 1940 he was the recipient of the Spingarn Medal for "his contribution to the healing of mankind and for his courageous position in the face of bitter attack."[13]

There is no such thing as Negro health ... the health of the American Negro is not a separate racial problem to be met by special segregated setups or dealt with on a dual standard basis, but is an American problem which should be adequately and equitably handled by the identical agencies and met with the identical methods that deal with the health of the remainder of the population.

— Louis T. Wright, Address at the 1938 National Health Conference[9]

Death and legacy

Wright suffered chronic health problems following his war service and was hospitalized for tuberculosis from 1939 to 1942. Though he returned to medicine thereafter and was appointed chief of surgery in 1943, he never fully recovered and died in 1952 at the age of 61.[2]

Throughout his career Wright published research extensively and his research proved influential in a number of areas including antibiotic treatment, cancer research, chemotherapy, treating head injuries, and treating bone fractures.[2]

The Harlem Hospital library was renamed in his honor just before he died.[2]

" What the Negro physician needs is equal opportunity for training and practice—no more, nor less."[14]

— Louis T. Wright

Fictional portrayals

Wright is the inspiration for the character Algernon Edwards, played by actor Andre Holland, in the Cinemax television drama series The Knick. Edwards, like Wright, graduated at the top of his class at Harvard Medical School and serves as the first African-American surgeon at the fictionalized Knickerbocker Hospital in Manhattan. Whereas the Harlem Hospital consisted a previously all-white surgical staff serving primarily African-American patients, the hospital in The Knick is an all-white surgical staff serving primarily white patients. While Edwards, active two decades prior to Wright, was not involved in broad-scale civil rights activism, the racial injustice he and others must contend with is a major theme of the show.[9][15][16]

References

- "Louis Tompkins Wright, MD, FACS, 1891–1952". American College of Surgeons. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony; Gates Jr., Henry Louis, eds. (2004). "Wright, Louis Tompkins". Civil Rights: An A-to-Z Reference of the Movement That Changed America. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Running Press. p. 464.

- "Kenyon College". Northbysouth.kenyon.edu. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- "Wright, Louis T. (Louis Tompkins), 1891-1952. Papers, 1879, 1898, 1909-1997: Finding Aid". Harvard University Library. 13 June 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- Reynolds, P. Preston (June 2000). "Dr. Louis T. Wright and the NAACP: Pioneers in Hospital Racial Integration". American Journal of Public Health. 90 (6): 883–892. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.6.883. PMC 1446256. PMID 10846505.

- "Jane Cooke Wright", Encyclopedia of World Biography (2008)

- "Louis Tompkins Wright, MD, FACS, 1891–1952". American College of Surgeons. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- "Wright, Louis T. (1891-1952) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". blackpast.org. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- Thomas, Karen Kruse (11 August 2014). "The Politics of Early Surgery: Review of 'The Knick'". Medpage Today.

- "University of Washington". Faculty.washington.edu. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- "Medicine: Negro Fellow. Time Magazine, 29th October 1934". Time.com. 1934-10-29. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- "Louis T. Wright, surgeon and NAACP Chairman - African American Registry". African American Registry. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- NAACP Spingarn Medal Archived 2010-07-07 at the Wayback Machine

- "Topic | Dr. Louis T. Wright | The History of African Americans in the Medical Professions". chaamp.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- Hay, Mark (3 September 2014). "The Hygiene Fiend Who Inspired Gory New Drama 'The Knick'". Good Magazine.

- Gipson, Grace (4 September 2014). "Before modern medicine there was the New York Knickerbocker Hospital ... Cinemax's New Late Summer Series, "The Knick"". The Berkeley Graduate. Archived from the original on 24 November 2014.

Further reading

- Buckely, Joann H.; Fisher, W. Douglas (2016). African American Doctors of World War I: The Lives of 104 Volunteers. McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 9781476663159.

- Gates Jr. Henry Louis; Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks, eds. (2009). Harlem Renaissance Lives. From the African American National Biography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195387957.

- Thomas, Karen Kruse (2011). Deluxe Jim Crow: Civil Rights and American Health Policy, 1935-1954. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820330167.