Niagara Movement

The Niagara Movement was a black civil rights organization founded in 1905 by a group of civil rights activists– many of whom were among the vanguard of African-American lawyers in the United States –led by W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter. It was named for the "mighty current" of change the group wanted to effect and Niagara Falls, near Fort Erie, Ontario, where the first meeting took place, in July 1905. The Niagara Movement was organized to oppose racial segregation and disenfranchisement. It opposed what its members believed were policies of accommodation and conciliation promoted by African-American leaders such as Booker T. Washington.

Background

During the Reconstruction Era that followed the American Civil War, African Americans had an unprecedented level of civil freedom and civic participation, especially the freedmen in the Southern United States, who voted for the first time and could contract for their labor. With the end of Reconstruction in the 1870s, their freedoms began to narrow. From 1890 to 1908, all the Southern states ratified new constitutions or laws that disenfranchised most blacks and significantly restricted their political and civil rights.[2] All of them passed laws imposing legal racial segregation in public facilities. These policies were entrenched after the United States Supreme Court in 1896 ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that laws requiring "separate but equal" facilities were constitutional.

The most prominent African-American spokesman during the 1890s was Booker T. Washington, leader of Alabama's Tuskegee Institute. In an 1895 speech in Atlanta, Georgia, Washington discussed what became known as the Atlanta Compromise. He believed that Southern African-Americans should not agitate for political rights (such as exercising the right to vote or having equal treatment under the law) as long as they were provided economic opportunities and basic rights of due process. He believed they needed to focus on education and work, to raise their race.[3] Washington politically dominated the National Afro-American Council, the first nationwide African-American civil rights organization.[4]

By the turn of the 20th century, other activists within the African-American community began demanding a challenge to racist government policies and higher goals for their people than those advocated by Washington. They believed that Washington was "accommodationist". Opponents included Northerner W. E. B. Du Bois, then a professor at Atlanta University, and William Monroe Trotter, a Boston activist who in 1901 founded the Boston Guardian newspaper as a platform for radical activism.[5][6] In 1902 and 1903 groups of activists sought to gain a larger voice in the debate at the conventions of the National Afro-American Council, but they were marginalized because the conventions were dominated by Washington supporters (also known as Bookerites).[7] Trotter in July 1903 orchestrated a confrontation with Washington in Boston, a stronghold of activism, that resulted in a minor melee and the arrest of Trotter and others; the event garnered national headlines.[8]

In January 1904 Washington, with funding assistance from white philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, organized a meeting in New York to unite African American and civil rights spokesmen. Trotter was not invited, but Du Bois and a few other activists were. Du Bois was sympathetic to the activist cause and suspicious of Washington's motives; he noted that the number of activists invited was small relative to the number of Bookerites. The meeting laid the foundation for a committee to include both Washington and Du Bois, but it quickly fractured. Du Bois resigned in July 1905.[9] By this time, both Du Bois and Trotter recognized the need for a well-organized anti-Washington activist group.

Founding

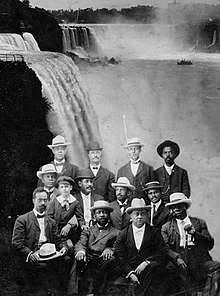

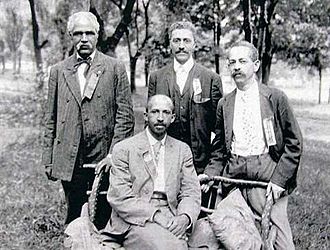

Along with Du Bois and Trotter, Fredrick McGhee of St. Paul, Minnesota and Charles Edwin Bentley of Chicago had also recognized the need for a national activist group.[10] The foursome organized a conference to be held in the Buffalo, New York area in the summer of 1905, inviting 59 carefully selected anti-Bookerites to attend. During July 11 - 13, 1905, 29 individuals met at the Erie Beach Hotel[11] in Fort Erie, Ontario, Canada, across the Niagara River from Buffalo.

Founders

The 29 founders who traveled to the inaugural meeting of the Niagara Movement from 14 states became known as "The Original Twenty-nine":[12][13]

- James Robert Lincoln Diggs – College president; pastor; ninth African American to receive a doctorate in the United States

- Dr. Henry Lewis "H. L." Bailey (January 17, 1866 – July 16, 1933) – Teacher and medical doctor.[14]

- William Justin "W. Justin" Carter, Sr. (May 28, 1866 – March 23, 1947)[15] – Pennsylvania lawyer; civil right activist; scholar; early NAACP member[16]

- William Henry "W. H." Scott (June 15, 1848 – June 27, 1910)[17] – Born to slavery, soldier, teacher, bookseller, Baptist pastor, activist, founder of Massachusetts Racial Protective League and the National Independent Political League[13]

- Isaac F. "I.F." Bradley, Sr. (1862 – 1938) – Assistant county attorney, Wyandotte County; justice of the peace; judge; publisher and editor of The Wyandotte Echo (1930 – 1938)[18]; father of Isaac F. Bradley, Jr., who was assistant attorney general for Kansas (1937-39)[19]

- Alonzo F. Herndon – Born to slavery; entrepreneur; one of the first African-American millionaires in the United States

- William Henry "W. H." Richards (January 15, 1856 – 1941) – Lawyer and law professor; secured funding from Congress, with William Henry Harrison Hart, for first law school building at Howard University; activist; alderman; mayor;[13]William H. Richards: A remarkable life of a remarkable man, was a biography by Julia B. Nelson, published about 1900[20]

- Bergen Stelle "B. S." Smith – Born to parents who were born into slavery; orphaned young; activist; lawyer[13]

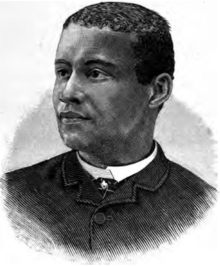

- Frederick L. McGheeW. E. B. Du Bois, 1903 portrait

- William Monroe Trotter

- Garnett Russell "G.R." Waller (February 17, 1857 – March 7, 1941) – Shoemaker; pastor[13]

- H. A. Thompson

- William Henry Harrison Hart — Born to a white slave trader; jailed activist; secured funding from Congress, with W. H. Richards, for first law school building at Howard University; law professor; worked for United States Treasury, United States Department of Agriculture; assistant librarian of Congress; first black lawyer appointed as special U.S. District Attorney for the District of Columbia

- Lafayette M. Hershaw

- W. E. B. Du Bois – Co-founder of the NAACP

- Charles E. Bentley

- Clement G. Morgan

- Freeman H. M. Murray

- J. Max Barber[21]

H. C. Smith, Men of Mark sketch.

H. C. Smith, Men of Mark sketch. - George Frazier Miller (November 28, 1864 – May 9, 1943) — rector of St. Augustine's Episcopal Church, Brooklyn; socialist; civil rights activist[13]

- G. H. Woodson

- James L. Madden

- Henry C. Smith – Musician, composer; civil rights activist; Ohio deputy oil inspector; co-founder and editor of The Cleveland Gazette[21]

- E. T. Morris

- Richard Hill

- Robert Bonner

- Byron Gunner

- E.B. Jourdain, Massachusetts

- George W. Mitchell, Pennsylvania

The organization founded at this meeting chose Du Bois as its general secretary and Cincinnati lawyer George H. Jackson as treasurer. It set up a number of committees to oversee progress on the organization's goals. State chapters would advance local agendas and disseminate information about the organization and its goals.[22] Its name was chosen to reflect the site of its first meeting and to be representative of a "mighty current" of change its leaders sought to bring about.[23]

Inaugural meeting location

There are differing explanations for why the group met in southern Ontario and not Buffalo. Although not substantiated by primary sources, it is often said that they had originally planned to meet in Buffalo, but were refused accommodation.[24][25] Du Bois's writings of the time, however, show that his original plan was to find a quiet, out of the way location for the event, and that the Erie Beach Hotel satisfied his requirements.

Researcher Cynthia Van Ness has located contemporary evidence that Buffalo hotels complied with a statewide anti-discrimination law passed in 1895.[26][27] Bookerites had been alerted to the planned conference, but one who traveled to Buffalo to investigate the proceedings did not find any activity.[22]

Declaration of Principles

The attendees of the inaugural meeting drafted a "Declaration of Principles," primarily the work of Du Bois and Trotter.[28] The group's philosophy contrasted with the conciliatory approach by Booker T. Washington, who proposed patience over militancy.[29] The declaration defined the group's philosophy and demands: politically, socially and economically. It described the progress made by "Negro-Americans",

"particularly the increase of intelligence, the buy-in of property, the checking of crime, the uplift in home life, the advance in literature and art, and the demonstration of constructive and executive ability in the conduct of great religious, economic and educational institutions."[28]

It called for blacks to be granted manhood suffrage, for equal treatment for all American citizens alike. Very specifically, it demanded equal economic opportunities, in the rural districts of the South, where many blacks were trapped by sharecropping in a kind of indentured servitude to whites. This resulted in "virtual slavery". The Niagara Movement wanted all African Americans in the South to have the ability to "earn a decent living".

On the subject of education, the authors declared that not only should it be free, but it should also be made compulsory. Higher education, they declared, should be governed independently of class or race, and they demanded action to be taken to improve "high school facilities." This they emphasized: "either the United States will destroy ignorance, or ignorance will destroy the United States."[30] They demanded for judges to be selected independently of their race, and for convicted criminals, white or black, to be given equal punishments for their respective crimes.

In his address to the nation, W. E. B. Du Bois stated, "We are not more lawless than the white race; we [are] more often arrested, convicted and mobbed. We want justice, even for criminals and outlaws." He called for the abolition of the convict lease system. Established after the Civil War before southern states built prisons, convicts were leased out to work as cheap laborers for "railway contractors, mining companies and those who farm large plantations." Southern states had passed laws targeting blacks and leasing them out to pay off fines or fees they could not manage. The system continued, earning money for local jurisdictions and the state from leasing out prisoners. There was little oversight, and many prisoners were abused and worked to death.[31][32] Urging a return to the faith of "our fathers," the declaration appealed for every person to be considered equal and free.

The declaration also targeted the treatment blacks received from labor unions, often oppressed and not fully protected by their employers nor granted a permanent employment. It validated the already announced affirmation that such protest against outright injustice would not cease until such discrimination did. Secondly, Du Bois and Trotter stated the irrationality of discriminating based on one's "physical peculiarities", whether it be place of birth or color of skin. Perhaps one's ignorance, or immorality, poverty or diseases are legitimate excuses, but not the matters over which individuals have no control. Near its end, the document condemns the Jim Crow laws, the rejection of blacks for enlistment in the Navy and by the military academies, the non-enforcement of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments protecting the rights of blacks, and the "unchristian" behaviors of churches that segregate and show prejudice to their black brothers. The Declaration thanked those who "stand for equality" and the advancement of this cause.[28][33]

Opposition

Booker T. Washington and his supporters tried to discourage growth of this rival movement. Washington, Thomas Fortune, and Charles Anderson met after learning of the Movement's formation, and agreed to suppress news of it in the black press.[34] They acquired supporters in Archibald Grimké and Kelly Miller, two moderates who had been friendly with Trotter, but had not been invited by Du Bois to the convention (Grimké was hired by Fortune's New York Age). The Age editorialized that the Movement was little more than an attempt to tear down the house that Washington had labored to set up.[35] A Boston supporter of Washington convinced the printer of Trotter's Guardian to withdraw his services, but Trotter managed to continue printing anyway.[36] Prominent white activists, including Francis Jackson Garrison and Oswald Garrison Villard (sons of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, a hero of Trotter), refused to attend Trotter-organized commemorations of their father's birth centennial.[37] They chose a celebration organized by Bookerites.[38]

Despite Washington's attempts at suppression, Du Bois reported at the end of 1905 that a number of black publications had published accounts of the Movement's activities, and it received further publicity as a consequence of Bookerite press attacks against it.[39] Washington also attacked the Constitution League, a multi-racial civil rights group that was also opposed to his accommodationist policies. The Movement made common cause with this organization.[40]

Activities

After the initial meeting, delegates returned to their home territories to establish local chapters. By mid-September 1905, they had established chapters in 21 states, and the organization had 170 members by year's end.[41] Du Bois founded a magazine, the Moon, in an attempt to establish an official mouthpiece for the organization. Due to lack of funding, it failed after a few months of publication.[42] A second publication, The Horizon, was started in 1907 and survived until 1910.[43][44]

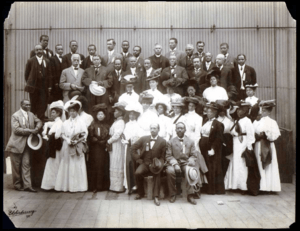

The movement's second meeting, the first to be held on U.S. soil, took place at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, the site of abolitionist John Brown's 1859 raid. The three-day gathering, from August 15 to 18, 1906, took place at the campus of Storer College (now part of Harpers Ferry National Historical Park). Convention attendees discussed how to secure civil rights for African Americans, and the meeting was later described by Du Bois as "one of the greatest meetings that American Negroes ever held." Attendees walked from Storer College to the nearby Murphy Family farm, relocation site of the historic fort where John Brown's quest to end slavery reached its bloody climax. Once there they removed their shoes and socks to honor the hallowed ground and participated in a ceremony of remembrance.[25]

Several of the organization's chapters made substantive contributions to the advance of civil rights in 1906. The Massachusetts chapter successfully lobbied against state legislation for the segregation of railroad cars, but was unable to stop the state from helping to fund the Jamestown Exposition, a commemoration of the founding of racially motivated Jamestown, Virginia, in which Virginia sought to limit black admission. The Illinois chapter convinced Chicago theater critics to ignore a production of The Clansman.[45]

During the early months of 1906 friction began to develop between Du Bois and Trotter over the admission of women to the organization. Du Bois supported the idea, and Trotter opposed it, but eventually relented, and the matter was smoothed over during the 1906 meeting.[46] Their division became more significant when Trotter split with longtime supporter and Movement member Clement Morgan over Massachusetts politics and control of the local Movement chapter, with Du Bois siding with the latter.[47] When the Movement met in Boston in 1907 Du Bois not only admitted Grimké and Miller to the organization, he reappointed Morgan to a leading position in the organization.[48] Further attempts to heal the rift failed, and Trotter then resigned from the Movement.[49]

In 1906 there were several proposals floated in the black press that the Movement be merged with other organizations. None of these proposals got off the ground, with the only substance being a meeting between the Movement's Washington, DC chapter and members of the Bookerite National Afro-American Council.[50]

The Movement, in conjunction with the Constitution League (which took Du Bois on as a director), began organizing legal challenges to segregationist laws in early 1907. For an organization with a limited budget, this was an expensive proposition: the single case they mounted challenging Virginia's railroad segregation law put the organization into debt.[43]

Du Bois had sought to return to Harpers Ferry for the 1907 annual meeting, but Storer College refused to grant them permission, claiming the group's presence in 1906 had been followed by financial and political pressure from its supporters to distance itself from them. The 1907 meeting was held in Boston, with conflicting attendance reports. Du Bois claimed 800 attendees, while the Bookerite Washington Bee claimed only about 100 in attendance.[51] The convention published an "Address to the World" in which it called on African-Americans not to vote for Republican Party candidates in the 1908 presidential election, citing President Theodore Roosevelt's support for Jim Crow laws.[52]

End of the Movement

William Monroe Trotter's departure after the 1907 meeting had a serious negative impact on the organization, as did disagreements about which party to support in the 1908 election. Du Bois, with some reluctance, endorsed Democratic Party candidate William Jennings Bryan, but many African-Americans could not bring themselves to break from the Republicans, and William Howard Taft won the election, receiving significant African-American support.[53] The 1908 annual meeting, held in Oberlin, Ohio, was a much smaller affair, and exposed disunity and apathy within the group at both local and national levels.[54] Du Bois invited Mary White Ovington, a settlement worker and socialist he had met in 1904, to address the organization. She was the only white woman to be so honored.[55] By 1908 Washington and his supporters successfully made serious inroads with the press (both white and black), and the Oberlin meeting received almost no coverage.[56] Believing the Movement to be "practically dead", Washington also prepared an obituary of the organization for the New York Age to publish.[44]

In 1909, chapter activities continued to dwindle, membership dropped, and the annual meeting (held at Sea Isle City, New Jersey) was a small affair that again received no significant press. It was to be the organization's last meeting.[57]

Legacy

In the wake of the Springfield Race Riot of 1908, a major race riot in Springfield, Illinois in August 1908; a number of prominent white civil rights activists called for a major conference on race relations. Held in New York City in early 1909, the conference laid the foundation for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which was formally established in 1910. In 1911, Du Bois (who was appointed the NAACP's director of publications) recommended that the remaining membership of the Niagara Movement support the NAACP's activities.[44] William Monroe Trotter attended the 1909 conference, but did not join the NAACP; he instead led other small activist civil rights organizations and continued to publish the Guardian until his death in 1934.[58][59]

The Niagara Movement did not appear to be very popular with the majority of the African-American population, especially in the South. Booker T. Washington, at the height of the Movement's activities in 1905 and 1906, spoke to large and approving crowds across much of the country.[60] The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot hurt Washington's popularity, giving the Niagarans fuel for their attacks on him.[61] However, given that Washington and the Niagarans agreed on strategy (opposition to Jim Crow laws and support of equal protection and civil rights) but disagreed on tactics, a reconciliation between the factions began after Washington died in 1915.[62] The NAACP went on to become the leading African-American civil rights organization of the 20th century.

See also

References

- "Niagara Movement:Selected Sources in the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library", July 2012, page 1. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Klarman, Michael (2004). From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780195351675. OCLC 159922058.

- Brown, Nikki; Stentiford, Barry, eds. (2008). The Jim Crow Encyclopedia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 9780313341823. OCLC 369409006.

- Fox, pp. 46–48.

- Fox, pp. 29–30.

- Lewis, pp. 179–182.

- Fox, pp. 38–40.

- Fox, pp. 49–58.

- Lewis, pp. 208–211.

- Fox, p. 89.

- "Niagara Movement First Annual Meeting" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 18, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- "Niagara Movement, 'The Original Twenty-Nine', 1905", W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (Series 17. Photographs [IMAGE depicts 27 of 29 founders), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Retrieved October 12, 2019.]

- African American Civil Rights: Early Activism and the Niagara Movement, by Angela Jones, Praeger, ABC-CLIO, 2011, page 229. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- Biographical Dictionary of American Physicians of African Ancestry, 1800-1920, by Geraldine Rhoades Beckford, Africana Homestead Legacy, 2013, page 15. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- Harrisburgh Evening News obituary , March 26, 1947 via Geocities. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- "Race, Social Science and the Crisis of Manhood, 1890-1970: We are the Supermen, by Malinda A. Lindquist, Routledge, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- SCOTT, WILLIAM H. (WILLIAM HENRY), 1848-1910. William H. Scott family papers, 1848-1982, Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, archived 2012, page 2. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- "Early black graduates exemplify how diversity makes us better", by Aaron Holmes, "KU Law Blog", University of Kansas School of Law, March 3, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- Emancipation: The Making of the Black Lawyer, 1844-1944, by J. Clay Smith, Jr. (1885 – 1975), University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999, page 519.

- William H. Richards : a remarkable life of a remarkable man, by Julia B. Nelson, Murray Bros. Press.

- Men of mark; eminent, progressive and rising by Rev. Wm. J. Simmons, Geo. R. Rewell & Co., Ohio, 1887, page 194.

- Fox, p. 90.

- Ali, Omar (2009). In the Balance of Power: Independent Black Politics and Third-Party Movements in the United States. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. p. 110. ISBN 9780821418062. OCLC 756717945.

- Wormser, Richard. "Niagara Movement 1905-10". The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow. PBS. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

- Gilbert, David T. (August 11, 2006). "The Niagara Movement at Harpers Ferry". National Park Service. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

- "NIAGARA MOVEMENT - A Mystery Solved!". University at Buffalo. 2005. Archived from the original on August 29, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

- Van Ness, Cynthia (Winter 2011). "Buffalo Hotels and the Niagara Movement: New Evidence Refutes an Old Legend". Western New York Heritage Magazine. 13 (4): 18–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on

|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). Retrieved June 10, 2020. Van Ness says that the "Malby Law" (1895) prohibited discrimination in hotels on the basis of color, and The New York Times reported on a successful test of that state law in Buffalo, thus making the hotel legend unlikely. - "The Niagara Movement's "Declaration of Principals"". Black History Bulletin. 68 (1): 21–23. March 2005.

- Brinkley, Alan (2010). "Chapter 20 - The Progressives". The Unfinished Nation. McGrawHill. ISBN 978-0-07-338552-5.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (August 16, 1900). "Address to the Nation". Harper's Ferry, West Virginia: Second annual meeting of the Niagara Movement. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- Wells, Ida B; Frederick Douglass; Irvine Garland Penn; Ferdinand L. Barnett (1999). "Chapter 3: The Convict Lease System". The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World's Columbian Exposition: The Afro-American's Contribution to Columbian Literature. Illinois: University of Illinois Press. p. 23.

- Douglas Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name

- Williams, Scott. "The Niagara Movement". Department of Mathematics, University at Buffalo. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- Fox, p. 92.

- Fox, p. 95.

- Fox, p. 97.

- Fox, p. 99.

- Fox, p. 100.

- Rudwick, pp. 180–181.

- Rudwick, pp. 183–185.

- "Du Bois Central: Resources on the life and legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois. Niagara Movement". Special Collections and University Archives, W.E.B. Du Bois Library, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2009.

- Fox, p. 101

- Rudwick, p. 190.

- Rudwick, p. 198.

- Rudwick, p. 187.

- Fox, p. 103.

- Fox, pp. 104–106.

- Fox, p. 108.

- Fox, pp. 109–110.

- Rudwick, pp. 187–189.

- Rudwick, p. 191.

- Rudwick, p. 192.

- Rudwick, pp. 194–195.

- Rudwick, pp. 195–198.

- Wolters, Raymond (2003). Du Bois and His Rivals. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8262-1519-2.

- Rudwick, p. 196.

- Rudwick, p. 197.

- Fox, pp. 128–130, 260–270.

- Schneider, Mark (1997). Boston Confronts Jim Crow, 1890–1920. Boston: Northeastern University Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 9781555532963. OCLC 35223026.

- Norrell, pp. 331–336.

- Norrell, pp. 338–347.

- Norrell, p. 422.

- Fox, Stephen (1970). The Guardian of Boston: William Monroe Trotter. New York: Atheneum Press. OCLC 21539323.

- Lewis, David (2009). W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biography. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 9780805087697. OCLC 176972569.

- Nahal, Anita; Lopez, D. Matthews Jr. (July 2008). "African American Women and the Niagara Movement, 1905-1909". Afro-Americans in New York Life and History. 32 (2).

- Norrell, Robert (2009). Up from History: The Life of Booker T. Washington. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press. ISBN 9780674032118. OCLC 225874300.

- Rudwick, Elliott (July 1957). "The Niagara Movement". The Journal of Negro History. 42 (3): 177–200. doi:10.2307/2715936. JSTOR 2715936.