Louis François Henri de Menon

Louis-François-Henri de Menon, Marquis de Turbilly (Fontenailles, 1717 – Paris, 25 February 1776) was a French agronomist, who wrote Mémoire sur les défrichements in 1760

Biography

Louis-François-Henri de Menon was born in a distinguished family from Anjou, which had acquired an estate in the province of Anjou by marriage in the 14th century.[1] De Menon took his studies at the college of the Jesuits of La Flèche.

Military career

After his studies he entered the regiment of Normandy in 1733. During the War of the Polish Succession, he distinguished himself at the Siege of Philippsburg in 1734.

Made captain in 1737, he was assigned to cavalry regiment from Roussillon in 1740. After the death of his father in 1737, he became landowner of a considerable estate, where he began making great improvement by rationalising the work. In the War of 1741 recalled to his regiment, leaving his estate in the hands of a capable manager.

During the War of the Austrian Succession, de Menon fought in Bohemia, in Westphalia, and eventually integrated into the Regiment of Saxony. He received the Order of Saint Louis before attending the sieges of Antwerp and Brussels, and the Battle of Rocoux. Seriously wounded in the Battle of Lauffeld in 1747, he had to leave the army.

Agriculture

Louis-François-Henri de Menon retired to his estates in the South of Mayenne, in the province of Anjou, in the commune of Villiers-Charlemagne. He is known for his dissertation on the deforestation. Of the inherited estate, an area located in Baugé about 1000 hectares, in 1737 most of which was still uncultivated. He improves the land by clearing (removal of forest), and adding drainage, turing it into a model estate. He cleared the heather, that covered most of the land around the town of Villiers, and created pathways to make the land more productive. Forty years later his territory had become one of the richest in the province.

He became friend and adviser to the minister Bertin. He inspired a circular initiated 22 August 1760, in which people were invited to create Agricultural societies.[2] He also influenced the decision of the French Parlement of 16 April 1761 in favour of deforestation. He was elected fellow of the Royal Society, 22 April 1762 under the name Francois-Henri, Marquis de Turbilly.[3]

He initiated two awards for the best and most beautiful wheat and rye harvested in the commune. The awards consist of a sum of money and a medal. It was the first of its kind given in France. Another of his ideas was the establishment of agricultural societies in the country. Another of his ideas was to abolish the practice of begging, on which he succeeded in his lands.

De Menon also develops new activities such as the cultivation of hemp; the rearing of silkworms for the production of silk; and a small factory for the production of soap and another unit for the production of terracotta roof tiles. Towards the end of his life he initiated fish farming. His latest project to produce porcelain turned into a legal and financial nightmare. His large enterprises had asked immense capital. Some of its operations did not succeed in the first years, and eventually he got totally ruined.[1] While the creditors were seizing his property, De Menon had turned over his administration just before his death in Paris on 25 February 1776.

Legacy

De Menon had no children. After his death in 1776 his land was sold by the creditors, and the estate was bought by an Irish nobleman. It was visited by the English agronomist Arthur Young in 1787, who had especially travelled from England to Mayenne to investigate the work of De Menon. English farmer found prominent remains of the improvements made during nearly forty years, and he gave an interesting account in first volume of travel reports.

Voltaire immortalised de Menon (Marquis of Turbilly) in his Epître à madame Denis sur l'agriculture (Epistle to Madame Denis on agriculture), stating:[4]

- D’un canton désolé, l'habitant s’enrichit

- Turbilly dans l'Anjou t'imite et t'applaudit

However Voltaire is neither named nor identified his work in his Mémoire sur les défrichements (Memorandum on clearing).

In the third corrected and improved edition of The Complete Farmer: Or, a General Dictionary of Husbandry, published in 1777, De Menon (as Marquis de Turbilly), was listed in the subtitle among the foremost authorities. Other people mentioned in the subtitles of this work were Carl Linnaeus, Michel Lullin de Chateauvieux, Hugh Plat, John Evelyn, John Worlidge, John Mortimer, Jethro Tull, William Ellis, Philip Miller, Thomas Hale, Edward Lisle, Roque, John Mills, and Arthur Young.[5]

Publications

- Marquis de Turbilly. Mémoire sur les défrichements, Paris: chez la Veuve d'Houry, 1760

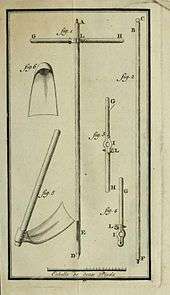

- Marquis de Turbilly. Observations sur la sonde & l'ecobuë Paris: chez la veuve d'Houry, 1760

- Marquis de Turbilly. Discourse on the cultivation of waste and barren lands. Londres, 1762. First edition in English of Mémoire sur les défrichements,.

About Marquis of Turbilly

- Sauvy, Alfred, and Jacqueline Hecht. "[ La population agricole française au XVIIIe siècle et l'expérience du marquis de Turbilly]." Population (French Edition) (1965): 269–286.

- Guillory, Pierre Constant. Notice sur le marquis de Turbilly: agronome Angevin du XVIIIe siècle. Cosnier et Lachèse, 1849.

- Guillory, Pierre Constant, et al. Le Marquis de Turbilly, Agronome Angevin du XVIIIe siècle. 1862.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Louis François Henri de Menon. |

- Arthur Young Travels in france during the years 1787, 1788 & 1789. 1792, p. 121

- Sée, Henri. "les sociétés d'agriculture leur role a la pin de l'ancien régime" Annales révolutionnaires (1923): 1–16.

- De Beer, Gavin Rylands. "The relations between Fellows of the Royal Society and French men of science when France and Britain were at war." Notes and records of the Royal Society of London (1952): 244–299.

- Guillory, Pierre Constant, et al. Le Marquis de Turbilly, Agronome Angevin du XVIIIe siècle. 1862. p. 268

- The Complete Farmer: Or, a General Dictionary of Husbandry. 3rd ed. 1777.